The strange size of stories

Life was smithereens of decisions and constant problems and challenges. And so were her stories. She stuck the smithereens of stories together with home-made glue, with the cracks between them still visible and the glue all pungent, and made a novel.

Someone else kept a diary the old fashioned way, with smithereens of thoughts jotted into a notebook he kept tucked under his pillow. And Eduardo Galeano wrote history as a series of little stories in Memories of Fire, and in Children of the Days he wrote one vignette for each day of the year. In the ancient Indian text Panchatantra, interrelated animal fables in verse and prose were arranged within a frame story. Considered a treatise on political science and human conduct, the stories were based on old oral traditions. In Japan, there was the Zuihitsu genre, where the writer observed and pondered their surroundings in loosely connected personal essays and fragments of ideas. And a Venezuelan friend of mine wrote a book based on the random and strange stories of what went on in one squishy, dark, poet infested little pub in the Andes.

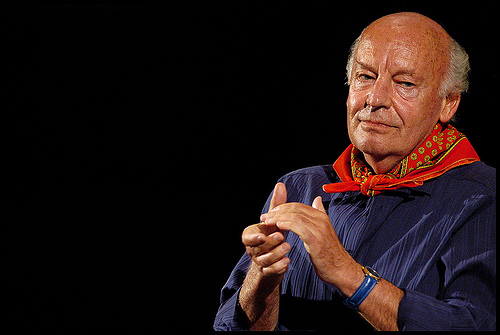

Eduardo Galeano

Galeano, unsure if his vignette series counted as a novel or an essay or a huge poem, said, “I do not believe in the frontiers that, according to literature’s customs officers, separate the forms.”

People wrote smithereen-ed stories because their reckless, tedious, abusive, surprising, contradictory and hypocritical lives usually weren't sequential, seamless novels. And neither was history. Watch the revolutions fail, die, then re-surge again in new forms. Watch the social struggles win equality and then watch those gains be distorted and dirtied by those with more power. Map out the victories, the failures, the steps forward and back, the surprising twists of history and the long uneventful bits, and notice how non-compliant and inconvenient it all is.

That was part of the magic. Another part though was the way people's stories touched each other, interacted and contrasted. They mixed, like honey and soy and lemon – maintaining their flavor but also creating something new. She sat in Mexico City's huge Zocalo square and watched the walking stories hurry past the giant flag, or wait for friends, or paint clown onto their faces so that they could beg with more efficiency. Those people – the little stories – formed part of a bigger picture; the story of a city that sat right on the edge of barely-alive, a city that was physically sinking, a city whose struggle against sell-and-buy defining life was being lost.

The small versions of big things

- A child carried a toy gun around with him in the shopping mall like a security blanket, while the US made billions in profits selling guns to the countries it had invaded.

- A teenage girl used a tape measure and her phone to calculate if her body was right or wrong, while double the amount of US women were murdered by partners or ex partners than US troops killed in Afghanistan and Iraq between 2001 and 2012.

- A toddler, wandering and daydreaming, got locked in a dead-bolted, fiberglass panic room, while the media sensationalized fear and terror and crime.

Pace and perspective

What speed does history travel at? What is the rhythm of humanity? What sort of chapters best capture the pace of life? What types of stories are most suited to a world where a quarter of the world seems to live on the Internet, and three-quarters are struggling with food and shelter? We're told it's the height of literary crime to break a reader's absorption, but what if we want to convey an unpeaceful reality? What if we want to provoke thought rather than entertain?

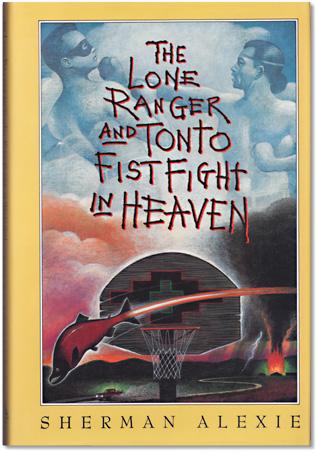

Look at Sherman Alexie's The Lone Ranger and Tonto Fistfight in Heaven. It's a collection of integrated stories about two Native-American men and their relationships and histories. Among the stories Alexie includes dream sequences, flashbacks, diary entries, and poetic passages. The chapters focus on different characters, thereby decentralizing the perspective and facilitating a human examination of an issue. Louise Erdrich also uses chapters narrated by different characters to show the inter-connectedness of a small group of Chippewa.

Vignettes and other short forms

A vignette is short – often one to four paragraphs, and it is more about communicating meaning than plot. It tends to give a sharp impression about a single thing, person, event or issue, and often takes place in a single moment. In the Spanish speaking world there is a fascination with vignettes, or what they refer to as “micro-stories”. Vignettes have a gamut of close relatives, including of course flash fiction, short short stories, micro narratives, and sudden fiction. There is even Twitter fiction, at 140 characters. The differences aren't too important for the purposes of this essay, though flash fiction does tend to be longer and have some kind of plot (obstacles, conflict, a changing character).

Then there are other short, thoughtful texts that can be played with, or incorporated into longer works, such as riddles, lateral thinking puzzles (hybrids of stories and puzzles that challenge assumptions and preconceptions), news briefs, parables (didactic stories with a lesson), epitaphs, and aphorisms.

“The micro-story rose with the idea of being read in one go, like a shot of whiskey drunk in one gulp. You feel the burning in your throat first, and afterwards in the stomach. The same sensation should stay in the memory of the reader,” said Spanish writer Gines Cutillas (my translation).

Every word counts in these shorter stories, and in vignettes, even the title has an important roll to play. It can be a comment, label, or description, and often alters the story's meaning and its reception. In Galeano's works, the title is often a paratext that forms a frame for the vignette.

Vignettes as tiny essays, story placards, postcards of injustice, single-image stories, little wisps of big ideas.

Story weaving and the art of story contrast

When I learned about Francisco Goya's The Third of May 1808 painting in school, I never realized what an impact it would have on my writing as an adult. To show the French soldiers slaughtering Spanish citizens, Goya put a rigid firing squad on one side – the rifles in line, their single duplicated posture creating a faceless force, and on the other he put the disorganized captives, with faces. The contrast is intense and thought provoking, and you can do the same thing with little stories. You can cause questions with the way you weave your stories. I wrote about police raiding a poor home in the one vignette, and then US soldiers patrolling an Iraqi street in the next.

Goya's Third of May 1808

And Galeano in Children of the Days used vignettes that mix journalism, history, and humanity to link the burning of Muslim books under order of the Holy Inquisition with the fate of America's indigenous peoples.

Naguib Mahfouz wove a universe with his vignettes. Nadine Gordimer described his Echoes of an Autobiography, his mosaic of reflections, allegories, memories, and visions as “pieces of meditation … in the words of the title of one of those prose pieces, 'The Dialogue of the Late Afternoon' of his life” . Yes, stories can be in dialogue with one another, just as our own days are, and we are with each other.

Thought spawning

Vignettes especially like to hit hard in their last line. Julio Cortazar was great at that. Watch as his story “The Lines of the Hand” describes a line from a letter that runs across the floor (yes, the line runs), over walls and a woman's back, to land in the hand of a person holding a pistol. The description of the line running is most of the little story, the hand with the pistol the surprising conclusion that makes the reader think about words and communication stopping violence.

Or his story about Cronopio, a little thing that finds a flower on its own and strokes its petals, blows on it to make it dance, and sleeps peacefully under it. The last line (my translation): “The flower thinks, “He's like a flower.”

And then there is one of the shortest stories, “The Migrant” by Luis Lomeli (my translation again):

- Have you forgotten anything?

- I hope so!

Short stories in sequences also offer time between them to reflect. Robert Olen Butler wrote head stories. InSeverance, he described the 90 seconds of consciousness of historical figures after they were decapitated. He looked at how people deal with death and toured history through people's mind. Readers need the space between each vignette to process those things.

Sandra Cisneros in The House on Mango Street also wrote her novel in vignettes. The short form and the accessible language made the novel easy to read and gave readers the physical space to dwell.

Time to process means time to doubt, wonder, get curious, and to challenge one's prejudices. Developing this capacity to analyze is part of our defense against vulnerability and being manipulated.

The value of brevity

Brevity also encourages readers to slow down and think, rather than gloss over and move on. Using just the most essential words entails more power and focus, as opposed to diluting down a story with unnecessary nice bits. No dawdling to get to the truth. Brevity also forces the writer to organize their ideas and be really clear about what they want to say. Try reducing a two page story to 100 words: all that remains is bones. Essence. Naked and transparent story without any clutter to obscure it. Prose poetry. The most amount of creativity and thought per word.

Galeano would rewrite his stories twenty times, until there was no fluff, just the most essential words.

Story placards and shareability

I used to be intimidated by museums. I was poor and unsophisticated, so museums felt like David Jones to me with their marble floors and grand entries; not my place to be. I thought art should be in the streets, bringing them color, available to everybody, and preferably replacing the billboard advertising. Now, the Internet is a kind of museum. Art, stories, anecdotes, short poems, photography, music are all on show and easily shareable. Does the Internet make for a good gallery? Are all the stories shared and read equally, and should they be? What does it mean for the world?

The virtual museum

Little stories are easily shared on social media and read among people and discussed. Like memes, stories can become personal placards – statements, about identity or a cause, when shared in public. Like murals, they can then interact with and form part of public life.

From online short stories based on Facebook updates, to the Word Museum's (Museo de la Palabra) daily vignette posts, to the Twitter micro-story competition organized by Argentina's The Outsider, to all the blogs and Tumblr accounts dedicated to short form prose or poetry, including one Tumblr account with short poems about the news, and another where people write stories based on gifs, to Reddit, where people often post personal anecdotes in response to a question, or stories in response to a prompt, writers' and readers' communities are organically sprouting up based on genre or theme rather than physical location.

Narrative blog and Tumblr accounts are often the modern, public version of journals and diaries. Little rants. And with younger Internet uses preferring content to be 300 words long (according to a study last year by Fractl and BuzzStream), and increasingly creative hashtags, sometimes it seems like prose has been democratized by the Internet. Yet readers can be bought, and story telling won't be democratic until there is much less global inequality and all voices are valued, not just the wealthy, male, first world, white voices.

Writer-teachers

The way we write (to a formula, creatively, analytically, in depth, superficially, obscurely etc) reflects and impacts on the way we learn, teach, and understand the world around us. The way we learn then impacts the way we grow and change things. Vignettes and other interconnected short story forms encourage reflection and didactic thought. Breaking the traditional writing rules liberates us to play, explore, and discover with our writing. As Ben Okri advocated, “breach and confront the accepted frontiers of things… to redream one's place in the world.”

The myth of the neutral writer

We are brought up with the notion that fact and fiction should not touch and that imagination and journalism's territories are separate nations and if one infiltrates the other's space, some kind of contamination occurs. This year's inequality stats have no place in the middle of a novel, for example. The notion is strongly connected to another one: that political opinions are dirty and taint a story. Meanwhile, the author is a god in the sky, all omnipresent, and disconnected from the world that he, she or other is attempting to describe.

In reality, writers, journalists, teachers, historians and economists – are entirely influenced by their living standards, the world they hate or love, if they work for free or for low pay or good pay, if their voices are elevated or they are part of a social group that is ignored or devalued. Virigina Woolf, in A Room of One's Own, wrote that women's writing in her time had a note of bitterness to it, because women had to fight to write, and men didn't. The role we play in society and where society puts us is reflected in our tone, our plots, our character choice, our style, and the very reason why we write. Why pretend otherwise?

Why not stick in a few facts that burn, a bit of context that adds a layer of meaning? Some would call it lecturing, yet the goal with vignettes and other techniques is just the opposite: to provoke questions, analysis, and new ideas.

George Orwell was reporting for the Observer while writing Animal Farm. He wrote that he didn't want to be political, but circumstances, such as the Spanish Civil War, obliged it. He saidi there were four reasons why writers write, the fourth being political purpose (where politics is about social forces and power, not just politicians). Writers want to push the world in a certain direction, he argued. “The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude,” he said.

George Orwell (in the back) with the Partido Obrero de Unification Marxista during the Spanish Civil War

His Homage to Catalonia has a chapter in it with newspaper quotes and a defense of the Trotskyists that were accused of plotting with Franco. A critic scolded Orwell, saying, “You've turned what might have been a good book into journalism.” Yet Orwell believed that, “What he said was true, but I could not have done otherwise. I happened to know what very few people in England had been allowed to know, that innocent men were being falsely accused. If I had not been angry about that I should never have written the book.”

Stories for justice

When I was little, my mum read me stories about Australian Aboriginals, women heroes and Black US heroes. I think they helped me question the world, question everything, and see my own life circumstances differently. Writers make political choices in most things they do. In a world where men's opinions are heard more than women's, where people in third world countries are victimized and Black people are stereotyped and the poor are ignored, who you chose as the narrator and as the main protagonists matters. It matters if you chose to reinforce stereotypes, or challenge them, if you create complex characters or simplified ones, and if your stories promote questions and analysis, or not. In that sense, a marriage (or a civil union) of journalism and imagination, of little stories and hard facts and research can challenge some of the unhealthy dominant narratives.

Naming problems and remembering history are the first steps in social change, and stories, especially small shareable ones (as well as well developed novels) can help do that.

“I know too that the powerful fear art … and that amongst the people such art sometimes runs like a rumour and a legend because it makes sense of what life's brutalities cannot, a sense that unites us, for it is inseparable from a justice at last. Art, when it functions like this, becomes a meeting-place of the invisible, the irreducible, the enduring, guts and honour,” John Berger said.

Stories can link the personal and political, and as Angela Davis said, teach people about the “intensely social character of their interior lives”.

And life

In school and the media, history is presented as an abstract thing, disconnected from our own lives. Politics is presented as being about politicians, maneuvers, and dates and policies. But social change is something lived, breathed, and artful. Little stories and big stories can counter that disconnect and engage people. They aren't above life, or detached from it, they can be a force within it. They can walk among us.

Red Wedge relies on your support. Our project is both urgent and urgently needed for cultivating a left-wing cultural resistance. If you like what you read above, consider becoming a patron of Red Wedge.

Tamara Pearson is a long time journalist based in Latin America with a degree in politics from Australia and another in alternative pedagogy from Venezuela. She is the author of The Butterfly Prison and blogs at resistancewords.wordpress.com.