“I dug up your past and I now know all of your moves / and I got witnesses statements and I got all of the proof / I’m wondering about you because I’ve got nothing to do / I notice you ending and I’ve got nothing to lose / I don’t know what’s gonna bring you down / I don’t know but I’m gonna bring you down “ --Lil Nas X, Bring U Down

Lil Nas X burst onto the music scene--in retrospect, an inevitable star--with the Tik-Tok viral single Old Town Road in xx 2019. The song reached number-one status on Billboard 100 and occupied the position for 19 weeks, the longest of any number-one hit in sixty-one years. In the course of his meteoric rise, Lil Nas X released several video versions of the single and an EP., “7,” appeared on the cover of Time Magazine and was nominated for several Grammys and a host of other music awards. In June, on the last day of the 50th anniversary of International Pride month, at the height of his moonshoot to stardom, X came out as “LGBTQ”[1] and then as “gay,”[2] nonchalantly saying, “deadass thought I made it obvious.”[3] For good measure, he then made it even more obvious, both in the content of his music and in the rainbow-themed art released with the EP. X went on to become the first openly gay artist nominated for a Country Music Award. At the Grammys, Lil Nas X walked away with two wins--“Best Music Video” and “Best Pop Duo/Group Performance”--after also being nominated for “Best Record,” “Best Album,” “Best Rap/Song Performance” and “Best New Artist.”

Pop music is often dismissed as formulaic. But It would be too easy to dismiss Lil Nas X as a pop sensation devoid of real intention or musical seriousness and simultaneously too simple to cynically read his assent as a premeditated and heavily marketed faux-viral sensation. To do either would be to misunderstand his achievement and his message, as well as to underestimate his music. “7,” taken in concert with his consummate social media campaign and persona, is instead both a compelling pop insta-classic and, in its own way, a deceptively funny, reverent ode to the history of pop, to hip hop, to rock and the gravity of queer and black genius as the driving historical force in American popular music. The real beauty is this: he knows it.

“7” is, above all, a coming out album. It was literally recorded in his actual closets at his family home and his grandmother’s house[4]. X says he hit the big time just as his family was growing tired of his all-in strategy to make and promote his music. He suspected he was about to be kicked out of his home just as his music career took off.

Any queer will recognize that pain and possibility in every 7 track--from Pannini, a ballad of mismatched love, genuine affection, regret, envy and resentment at being held back, to Family, which captures the importance of family in the moment of fearing its loss, the hope of fixing or recreating that fundamental base of support, and a gesture to the symbolic dream of white picket fences and two becoming three. Kick It is full of the homoeroticism of the closet and performative masculinity but with an unexpected spin on drug-dealing as care and bonding (with a rock opera aesthetic in hip-hop guise). Rodeo captures nominally heterosexaul sexual and social exploration. Bring U Down delivers the moment of rebellion from within/below, and then Closure seems to narratively resolve things with the open declaration of self-acceptance and actualization, though all the while we know of course the 7th is always itself a provocation and opening, awaiting future resolution, clearly the position of the debut album as a whole.

But each song has more coming out than a standard queer narrative can contain. The arc, musically and narratively, also refers to the “coming out” as a celebrity, as young, black, working class, and talented, simultaneously arch and sincere, committed to the underdog while on top of the world.

Ultimately, Lil Nax X’s music, and the context he created (or found) for it, manages to call upon the deep and recent history of black popular music in its most universalist iteration, to be totally ernest without self-seriousness, to embody the “trickster” modality of the African-American tradition and the related one of the queer pretender whose humor, undeniable talent, and campiness propels them above their station until its completely impossible that they wont be taken seriously even by the most self-deluded and dense bigots or patronzing patrons. Its very much of its time and generation, but with a seriousness about history that still also, always, manages to be funny.

Old Town Road : Video Game Memes Killed the Radio Star

By measure of musical quality and sophistication, X’s runaway hit Old Town Road (OTR) is the most underwhelming of the EP, but it was also his vehicle to stardom and itself a work of art in quite a different way. Based on a beat that X purchased for $30 online from Amsterdam-based producer Young Kio, who fashioned it out of a Nine Inch Nails sample,[5] the track’s first iteration was as a music video meme based entirely on images from the western-themed video game Red Dead Redemption 2.[6] Young Kio claims he never “heard of”[7] Nine Inch Nails before sampling the track; when it went viral, Trent Reznor granted use of the beat and said the song was “hooky.”[8] Kio and Reznor never intended the beat to be country music, but Lil Nas X had other ideas.

The received narrative is that a goofy kid struck it rich in the wild west of soundcloud and internet whimsy, but as Nas put it, “this is no accident;” he was striving for a “trap country” sound “leaning toward country” and had in mind from the start to bring Billy Ray Cyrus on board, which he did through twitter.[9] X credits his online birth as a consequence of a new kind of family, saying “the internet is like my parents, In a way” making him possible, but also tying him to the past of music, country music, black and queer music art and culture.

The second major video (there were many minor and fan versions along the way), Officially produced now featuring Billy Ray Cyrus, once OTR was riding the crest of weeks on number one makes this clear, an answer to the then growing backlash the single received from racist country fans[10] before and especially after Wrangler ™ offered Lil Nas X a sponsorship deal based on lyrics that directly referenced their classically country product (“my life is a movie/ bullriding and boobies, cowboy hats from gucci/wrangler on my booty”).

The 5 minute video is almost a whole film, clearly recalling the style and ethos of Blazing Saddles, full of celebrity cameos (Chris Rock as the first face we see, taking us back to an earlier moment when he was himself famous for that kind of incisive humor, with his opening line “when you see a black man on a horse going that fast/ you just gotta let him fly”) that make the sharply funny anti-racist points the 45 year old film did, via absurdist time travel from the old west to a geographically uninteliglble future, but one clearly built on the blatant racism and violence of settlerism ( the dialogue contiues, “I dont know man, last time i was here they werent to welcoming to outsiders” as a protective white settler-father chases them into a time portal, with gun shots in the background).

There X arrives, horse and tackle in tact, having escaped a comically violent white patriarch, into a 21st century working class black neighborhood visually depicted with a slo-mo cinematic drama making unlikely glamor out of circumstance and juxtaposition (Here he is greeted with friendly bemusement and curiosity, a young black man instructing surprised children in the art of respect for person and property, as he pays out what he owes for losing a drag race between horse and automobile: “ Hey Kwan! Get your children off the animal please! That’s his property we don't do that. You have have good day, get off my car.”

In this video context, several throwaway lyrics of the song suddenly take on new degrees of significance, astride the John Henryesque tale of an absurdist, mythic car vs horse speed-racing; “you can’t whip your Porsche” is the explanation given in the song for the magical prowess of horse and rider. Something living animates the capacity for unlikely victory, but also something painful, driven by oppression and danger, spurring on Lil Nas X as a character in a video, but also as the protagonist of his own public and artistic coming out. In the midst of a comic and truly lighthearted video, the direct confrontation with racism makes it impossible to forget, listening to that line, that whips were never just for horses.

All of the sudden, too, the lyric “ I’ve been in the valley/ you ain’t been up off that porch now” which introduces the chorus that hooked the world for 19 weeks--”cant nobody tell me nothing/you can’t tell me nothing” takes on import. It is a reference to Psalm 23:4, long imortalized in black church culture as a reference to slavery, in Langston Hughes poetry[11] ,and of course in dozens if not hundreds of samples of Gangsta’s Paradise, in which Coolio raps about the modern “valley of the shadow of doubt.” Lil Nas X has made it explicit that the response to that moment in the valley; the moment of rebellion was inspired by his determination to be out and queer, in the face of lifelong religous pressure to pray away the gay.[12]

The flipside is that cowboys were never just white, and have long been both symbols of the ultimate hypermasculine traditional american ideal and blatant lust objects of gay style and winking camp. Lil Nas X and Billy Ray end up performing to church crowd of line-dancing bingo-players and staff whose kitschy country aesthetic is suddenly revealed to be glamorous, intentional and above all owned and operated by the black women in the frame; framing, even just for a few lingering seconds does all this work for us. In Lil Nax X’s hands, country just isn’t and cant be white; that you might have ever thought it was, is the entire joke. Old Town Road is still here, were all still here.

This song and video, and the breadth and quality of its popularity reflect what is interesting that happens in a lyrically and melodically fairly simple, catchy track; rather than comparing the history of black and queer struggle, or contrasting serious somber reflections on opression, Lil Nas X manages to demonstate in practice their simultenety : “cant nobody tell me nothing” appeals much to veterans of the civil rights and black power movements as to billy ray cyrus as to queer millenials as to third graders across the globe (the third and last major video hit for OTR was a live performance X gave in an elementary school, where adorably, he bleeped the rated R lyrics out of his set while the children sing them at the top of thier lungs. Everyone appears to be having the time of their lives.)

Country Crossunder: Intellect and Savoir Faire

Lil Nax X rise as a country star and through it, his wholesome appeal to a broad audience, isn't just a gimmick or a joke; its a throwback and a ;continuation of some of the obscured origins[13] and best traditions[14] of Country Music. As a country music star, he is in some crucial ways most and best compared to the true queen of that broad appeal and working class traditionalism, Dolly Parton.

They seem really different. She’s a 74 year old megastar, a woman, white, from Appalachia, while he is a black 21 year old phenom from the Deep South; but they share an affinity for genre-bending, populism, feminism, over-the-top fashion sense and public self-fashioning. Dolly Parton’s America[15], a popular NPR podcast series explores over nine episodes Dolly’s life and work. In it, a few central themes emerge--- the premise is to investigate the appeal of Dolly Parton across race, nation, age and particularly across the USA-American culture war divide. How can Dolly at once speak to and represent the “traditional” mid-century country music so often associated with white racism, conservatism, sexism, family, faith and God, while at the same time appealing to an international, immigrant, feminist audience, old and young, black and white? The mystery, in the pod. Is cast as that of the “Dollyverse” and “Dollitics” ; the latter a term for Dolly’s specific tack of avoiding direct political commentary on bourgeois politics (Trump vs Democrats) while at the same time penning and performig presciently pro-immigrant feminist and pro-worker tunes like 9-to-5, Woody Guthrie’s Deportee, and Working Girl.

This question is traced back through her early career and songwriting, where her penchant for transforming country and folk conventions by writing songs from the perspective of women--first lovelorn, desperate, or even murdered, then empowered and free-- is revealed as the key to her staying power and appeal. That, along with her sincere and specific attention to a process of proletarianization that speaks to anyone missing the old homestead-- whether in the old mountain home of appalachia, the hills of agrarian Nigeria or the ex-urbs of Beiruit--explains the wide identification with Dolly and lends itself to easy Marxist cultural analysis.

Lil Nas X shares some of this approach and its resulting magic; when Dolly’s crypto-queer tease is incorporated the comparison becomes even more salient. Where Dolly sings about proletarianization from the land, X’s songs are about exclusion from and mismatch with heterosexuality, but also, through that, dispossession, a universal longing for love, family and acceptance. Where Dolly’s bold working class feminist motifs implicitly queer her, Lil Nax X queer black feminist perspective speaks class. Both make an art of relatability, calculated naturalness, timing and leaving some things unsaid.

The Dolly podcast devotes an entire episode to Jolene[16], a song long loved by women who love women for its detournement of the timeless country music genre of “other woman” song. By writing not only from the perspective of the betrayed wife, but as an appeal to Jolene and ode to her beauty, Dolly turns the mode on its head, denying the typical assumption of patriarchal competition, rage and violence, replacing it with relations between women as human and humane. The song, along with Dolly’s prematurely third-wave, high-femme self-posession has made her a particular favorite of the queer community, a love she openly returns, es[pecially as a long time champion of drag homage to her style and hers to that tradition, opining that if she hadnt been born female, she’d “be a drag queen.” [17]

Lil Nax X ‘s still much more sparse ouvre shares this technique with Dolly, even where it was, prior to his coming out plausibly-deniably heterosexual, taking up the perspective of women unexpectedly and insistuing on a gender and pespectival egalitariansim on an ontological level that sticks out in country music certainly, and does too in the rock and hip-hip genres he’s also clearly drawing on and contributing to. In Panini and Rodeo, he show two sides to disappointment with and points to an exit from heterosexuality, with a refreshingly egalitarian flair; in one, the refrain to a lover, apparently jealous of his success is “I thought you want this for my life/said you want to see my thrive/you lied” concluding with the appeal “just say to me/what you want from me, “ notably devoid of gendered hostility while evoking a familiar conflict.

In Rodeo, Cardi B, in duet, plays the role of powerful (older) woman clearly traumatized by men, but not defeated (Last n*gga did me dirty/Like a bathroom in a truck stop/Now my heart, it feels like Brillo/I'm hard like armadillo) while the narrator strikes a willfully submissive pose slicing through the premise of any nice/bad guy binary: “Oh, here we go/please let me know/Oh, 'fore you go/don't leave me in the cold/If I took you everywhere, then well, you wouldn't know how to walk/If I spoke on your behalf, then well, you wouldn't know how to talk/If I gave you everything and everything is what I bought/I can take it all back, I never cared 'bout what you thought.”

If Kick It was too easy as a song about being in the gay closet, the path to C7sure raises doubts that thwarted monosexual desire is all that Nas is talking about, even as he makes it clear that heterosexuality isnt what he’s about. Like Dolly, X takes on conventional “love gone bad” genres and turns them on their head, giving them a particular perspective that renders them more universal.

Dolly Parton has long denied rumors that she is “secretly” gay and in an relationship with her friend and confidant of decades, Judy Ogle[18]; a star who in many ways wears her heart on her sleeve she is intensely protective of her “private life” in the tradition of ambiguously gay and queer stars of her generation and later. This method undergirds the “Dollitics” described but under analyzed by NPRs podcast exploration of Dolly’s appeal; on the one hand its a classic case of the closet, but on the other its a version of ambiguity-as-seduction and even conversion, to both universalizing “gay” identity and radical class politics, not far off from that theorized by Mario Mieli in Towards a Gay Communism.

In that modality, to declare oneself can be not just a method of escaping erasure and dismissal but a trap, pinning you down in an affirmation that whatever you are is a thing others, straight people, and normal society are in some fundamental way not. There is something deeply conservative and pragmatic certainly about Dolly’s refusal to be named--she cites the career-ending attacks on the Dixie Chicks for opposing the second Iraq war as a reason--but also something that aims at a transformation bigger and more collective than naming a single person’s attributes or identity could every quite achieve.

Lil Nax X, stunningly, both managed to embrace this tradition to, while blowing it up with his dramatic coming out that still left questions deliciously unanswered. Dolly herself agreed, weighing in on whether or not Old Town Road is country, saying “"The fact that that was such a country song, I mean, that's as corny as any country song could be. I don't mean corny in a bad way. I don't care how we present country music or keep it alive. I hope it stays alive forever.” [19]

Smoke em if you got em

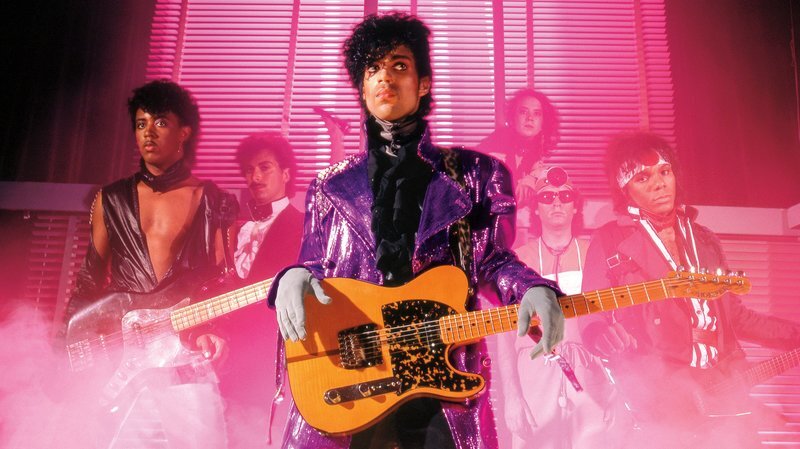

Even more than Dolly, Lil Nax X “crossover” success and meaning channels another indeterminately but obviously queer “crossover” megastar, Prince; he does so blatantly and with abandon. Lil Nas X even cosplayed prince at the 2019 MTV VMAs,[20] the allusion isn’t subtle.

That his LP is named “7,” the same name as Prince’s 1992 hit song referencing the seven deadly sins. The song is from from his album “Love Symbol,” which is the written version of Prince’s unpronounceable name, a symbol that combines male and female but is neither. In Prince’s words, it and he is “something you can never understand. “ Its easy to imagine now that the term non-binary might apply, but also that Prince might very well reject this in favor of enigma as he did throughout his career.

While Prince never “crossed over” to country, he played the iconic country and western guitar, a Fender Telecaster, his career was laced with racial and gender ambiguity, a commitment to rock, pop, R &B, disco and punk aesthetics determined to transcend the racial segregation of the music industry and any imaginable pigeon-hole. And like Prince, the question of gender is where Lil Nas X has pulled his punches on making any definitive statement; when he first came out it, it was as “LGBT”, and thus unclear which or all he meant; since then he’s been referred to as gay but also tweeted “just cuz i’m gay don’t mean i’m not straight,” and has avoided declaring himself non-binary, though the New York Times and gay gossip media have suggested it.[21]

Musically, there are fewer direct connections to Prince than say to Nine Inch Nails or Nirvana[22], but given that Prince’s 7 was initially planned a “rock opera” it is hard not to see X’s 7 as an attempt at some kind of fruition and intentional continuation of that aspiration. While Prince’s anthem declares the end of sin in the face of universal love, Lil Nas X 7 vaguely corresponds song for song with a “sin,” resolving or remaking it-- if OTR with all its comical product placement is “greed”, Panini is “envy”, Rodeo is “lust”, Kick It is “sloth”, and C7osure is “pride” (as self-realization), that leaves F9mily as “gluttony” --oblique, but perhaps describing a kind of temporarily self-gratifying white-picket fantasy “stand[ing] in the way of love,” at least the kind that lasts “through all space and time.”

This declared ambition; to embody the continuation of Prince legacy and take up his unfinished work is much bigger than any attempt to keep country alive or even to trick, play or thwart his detractors. Like Prince, X clearly aims to transform the pop genre (and even fashion[23]) beyond itself, to beat it at its own game and more, to take it seriously and make it look cool while he does it.

Tweeting to the Top, from Below

According to his own narrative, the social media hustle has been key to LIl Nax X success; but counterintuitively its not making it look easy that did it. Instead, even before his rise to stardom, X was semi-internet famous for having a hilarious twitter account, one that often and wrly exposed and lampooned reality and myths of class, with a knowing but positive sense of humor about things that garnered him an audience before his music debut, one he used to push OTR to the big time. Even as a “verified” star, his sense of humor and class orientation hasn’t changed all that ; he brings a typically “zennial” wry absurdist humor to jokes about getting by and even to the subject of his own success. [24]

Unlike his duet partner, Cardi B, a confirmed Berniebro and possible aspirant to formal politics[25] herself[26], Lil Nas X hasn’t endorsed any candidate for president in the USA elections or the Democratic Party. But after X came out on the last day of PRIDE, gay neoliberal candidate Pete Buttigieg declared his intention to appear and perform publicly with the rising star, presumably to add shine to his own “historic” candidacy. X shut the suggestion down[27]. Here, in saying he didnt want to “support any candidate” Lil Nax X is at his most Dolly; his vagueness in making explicit statements on its own could be read a liberal waffling, but as an action in rejecting an avatar of neoliberal gay assimilationist politics it conveys a much more radical message. Evocative of a growing movement and sensibility, it recalls the ethos of “Reclaim Pride,” a 45,000-strong response to this years World Pride events in New York, which marching uptown against the stream of heavily marketed and corporate official Pride events, and lead by Black and trans queer people, celebrants marched under the banner of reviving Stonewall on its 50th anniversary as an anti-cop, black, queer, trans and sex-worker-led anti-police riot, and in solidarity with Palestine.[28]

The New, Long Greatest Generation : From X to Z

This is also the meaning implicit and sometimes explicit of Lil Nax X music and persona as a “crossover” phenomenon. By taking on not just country, but rock, hip-hop and pop, and making it queer and making it Black, Lil Nas X is asserting or reasserting a set of ideas and traditions that have a longer history and immidiate genesis. His control of these genres even as a self-consciously “precocious” star is reminiscent of the more explicit assertions about the role of Black and African traditions in (US)American pop music; a reclamation of everything evocative of both Rock and Roll[29] and of the celebration of effeminacy and utopian aspiration and aesthetic of 20th century working class, black camp, drag, and trans culture famously captured in Paris is Burning: “you own everything!”[30]

Like a variety of artists ( like those in and around the okayplayer label[31]), who put forward an expansive and pro-Black political and “conscious” sensibility that stakes out the debt all popular genres owe to Black music generally and to Jazz in particular, Lil Nas X work asserts that “crossing over” doesn’t have to be about watered down non-threatening appeals. Where Gen X conscious rap made a point of resisting any attempt to define down hip hop as “low-brow” or uncomplicated, X at times feigns simplicity and naivete in a rhetorical and aesthetic style that evokes subcultural coding for those “in” and “out” of the know. If you get it, you get it. If not, you might like it anyway and who knows one day, you just might get it in the end. Unlike that Gen-X based musical movement for conscious rap, hip hop and jazz, he skips the appeals to overt or assumed heterosexulity and takes up an easy and assumed feminist and flexible approach to his craft.

Far from alone, Lil Nas X fame is the crest of a wave of creative, queer/trans, black-led and genre- and gender-bending hip hop, ranging from Mykki Blanco’s pathos-and-drug-fueled rap[32] to Big Freedia’s bid to bring Bounce from the Big Easy to the big time.[33] From Cakes da Killa[34] to FKA twigs[35] and even to break-through superstars--like Janelle Monae-- who made it first,[36] Lil Nas X strategy and success is rooted in a growing visibility and popularity of black queer artists who, like him, have built their popularity primarily online, seemingly skipping over older routes, through the underground and past older categories like “alt” or “conscious” that once marked similar artists as subcultural.

Yet Lil Nas X and even his and (once) more mainstream[37] collaborators signal that recognize the debt they owe to artists from those subcultural milieu. When X was still hustling on the internet, under the handle @NasMaraj (an ode to Nikki Minaj an Nas), Nikki Minaj recorded Romans Revenge with Eminem in a self-conscious ode to their shared “crossover” appeal, playfully and sometimes disturbingly toying their audience and with the idea of crossing not only racialized conventions of musical genre but those two of gender. In the song, Nikki does her best (and its quite good) imitation of Saul Williams[38]

Williams, born in 1972, is in many ways the angry and aggressive antecedent and necessary precursor to Lil Nas X’s jovial, popular antagonism with white supremacy and cis/heterosexuality. Building his career as an openly queer and “conscious” artist, (at a time when being out was strictly policed in hip-hop circles), Williams work referenced and references white and indeterminately queer rock superstars and their roots in Black American musical genres--especially Bowie.

Styling his alter-ego as “N*ggy Tardust,”(after Bowies alt, Ziggy Stardust), Williams addresses the white liberal “woke” part of his white audience directly calling out racism and shallow fandom. He manages to out-Bowie Bowie with his provocation, egging them on in a way dialectically opposite to that which an “anti-Politically Correct” comic, like Joe Rogan or Bill Maher might taunt their audience and guests into saying the “n-word.” Where Rogan would do this in order to “allow” his listeners and interlocutors to shout slurs as a kind of libidinal release and political aggression, Williams evokes and immediately destroys this of cheap seduction of resentment and bad-faith appeals to “reverse racism” .

The same action--setting up and provoking reluctant white people into using racial slurs-- in Saul Williams hands (N*ggy Tardust), is instead a humiliation that immediately demonstrates the fundamentally pathetic quality that allows anyone to be so provoked. Playing on African/African-American religious and spiritual traditions of call and response, Williams does so explicitly as a “comical absurdist” for whom “every word” is “ measured against meaning.” Meaning, for him, is so measured because racism requires it of Black people, but also because he is very very good at making and parsing meaning and wants everyone who can to appreciate it, and those who can’t get it to get out of the way and to know exactly why they should. Williams sets it up this way : “When I say n*ggy /you say nothing”/”..”/ “When I say n*ggy/ you say nothing” / “nothing” /“shut up”[43]

Williams, like Prince and Lil Nas X, uses Christian tropes while turning them on their head, in a reversal of homophobic and colonial images and discourse they have been used to justify. A major theme in Prince’s music is calling into being a cohort born to universal and universalizing love against all odds: his “New Power Generation.” For Prince these will throw the “thieves” from “the temple” and transcend sin in the terms which it has been handed down from on high, especially around gender, sexuality, segregation and anti-blackness. Similarly, Williams in DNA, sees himself as “Shepherd of a bastard flock” who “keep(s) my finger on the trigger/waiting for the right time” or at least as a seer anticipating a coming Prophet, while listening to the growing chorus of “angels on [his] Ipod.”

And so, Saul Williams’ signature song (Tardust) anticipates Lil Nax X or someone very like him: a a figure that transcends not only genre (like Prince and Bowie and many other before and contemporaneously to them) but does so while and because he transcends the closet, whitewashing and the sidelines. Williams’s lyrics even describe the improbable confidence and unlikely self-assurance Lil Nax X manifests, while evoking the range of historical possibility that potentiated his rise, another axis of parentage in addition to the metaphorical way X evokes the internet, necessary for that eventual birth but not sufficient:

Grippo King, philosopher, and artist

Downright to the marrow, he's the arrow through the heartless

Sunlight in the afternoon, his shadow travels furthest

Woven through the heart of doom, he's bursting through the surface

Hardly nervous, suffice to say, he understands his purpose:

Threshold King of everything, a comical absurdist

Sometimes when he talks he sings, yet keeps his high notes wordless

When Williams reminds us, now with Lil Nas X in mind, “Don’t call him by his name/White folks call him ‘Curtis’,” that the “X” itself calls up the history of Black radicalism and a tradition of rejecting slave names, and especially Malcolm X ( a towering figure long and credibly figured to be a bisexual forced by his political activity religious conviction and mid-century leadership profile into the closet.) We are suddenly aware that “Nas X” is both an homage to Nas, who, pace Biggie, Is probably New York City’s most prolific, skilled and commercially successful rap artist-- but it is also a critique.

It evokes some of the likeness between “slave” and “dead” names for queer and for Black people descended from ancestors who were enslaved and deprived of their names over generations; the way these renamings are most similar and inextricably intertwined, is in the way that they are a each a response, combining mourning with self-invention, fealty to antecedents with a self-aware freedom in inventing family and lineage. Where these structures all too often assumed to be fixed and natural and as a consequence, deployed toward repression and oppression, Lil Nas X genre flexibility and obsessive style of lyrical and musical reference reacts against this, expanding rather than narrowing or being narrowed by the limits of family expectations, gender, or market-driven restrictions on and erasure of unapologetically black and queer artistry.

LIke Williams, Nas X use of multiple genres, genders, beats, songs, images and influences is the opposite of a postmodern pastiche that loses meaning with every complication; instead, for both of them and the tradition from which they draw, reference, gesture, multiplicity, and indeterminacy are oriented toward making more meaning and toward specific ends They reflect a long tradition of poetry art and music that is fundamentally if not always explicitly Black and queer but always universalizing, a pulling in of multiple elements toward excavation and elevation, rather than a dumbing down and dishing out of pre-digested platitudes.

None of this is to claim that LIl Nas X personally represents some new political movement or is himself a political figure, activist, or writer of manifestos; instead he’s he necessary consequence and a uniquely talented individual expression of a new set of conditions. Historically conscious, socially adept and with whimsical sensibility that burst through now, precisely because now is when anyone like him first could have done so.

A dream for Prince, or even Dolly and Williams when they have imagined it, one line in Tardust evokes the magic and sense of realized possibility older (older than zennial anyway) queers and middle aged “ conscious” black fans might find in the artful artlessness of Lil Nas X stardom:

Side effects may include just being who you are.

Endotes

[1] Young, Alex. “Lil Nas X comes out on the final day of Pride” Consequence of Sound. June 30, 2019.

[2] Trammell, Kendall “Lil Nax X Tried to Explain Why He Came Out as Gay. Then Kevin Hart Hart Interrupted Him. CNN. Sept 4, 2019.

[3]https://twitter.com/LilNasX/status/1145470707150860289?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1145470707150860289&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fpitchfork.com%2Fnews%2Flil-nas-x-comes-out-as-gay%2F

[4] Coscarelli, Joe Alexandra Eaton, Will Lloyd, Eden Weingart, Antonio Luca and Alicia DeSantis “ ‘Old Town Road’: See How meme and Controversy Took Lil Nas X to the Top of the Charts. New York Times, video. May 10, 2019.

[5] 34 Ghost Iv

[6] Their, David. “Apparently, ‘Old Town Road is a ‘Red Dead Redemption 2’ Music Video. Forbes. April 9, 2019

[7]Coscarelli, Joe Alexandra Eaton, Will Lloyd, Eden Weingart, Antonio Luca and Alicia DeSantis “ ‘Old Town Road’: See How meme and Controversy Took Lil Nas X to the Top of the Charts. New York Times, video. May 10, 2019.

[8] Grow, Kory. “Trent Reznor Breaks Silence on ‘Undeniably Hooky’ ‘Old Town Road” Rolling Stone. October 25, 2019.

[9] Billy Ray Cyrus credits his wife with playing him the track, after Lil Nas X tweeted it at him, at which point he “got up out of his chair” it was so good, and since he is “grateful” for being: “included” in the experience. (Coscarelli et all, NYT)

[10] “Country Music Fans Boycott Wrangler Brand Following Lil Nas X Partnership” Vibe. May 21, 2019

[11] Shadows

[12] Young, Alex. “Lil Nas X comes out on the final day of Pride” Consequence of Sound. June 30, 2019.

[13] https://time.com/5673476/ken-burns-country-music-black-artists/

[14] https://www.jacobinmag.com/2019/11/a-forgotten-country/

[15] https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/dolly-partons-america

[16] https://www.wnycstudios.org/podcasts/dolly-partons-america/episodes/only-one-me-jolene

[17] https://www.georgetakei.com/dolly-parton-drag-queen-dumplin-2622858586.html

[18] https://www.theguardian.com/music/2019/feb/24/dolly-parton-on-sexual-politics-ive-probably-hit-on-some-people-myself

[19]https://theboot.com/dolly-parton-old-town-road-remix-lil-nas-x/

[20] https://www.papermag.com/lil-nas-x-mtv-vmas-2019-2640048339.html

[21] https://www.pinknews.co.uk/2019/11/29/dangly-earrings-new-york-times-non-binary-gender-fragile-masculinity-harry-styles/

[22] https://www.billboard.com/articles/news/8529122/lil-nas-x-frances-bean-cobain-approved-panini-nirvana-sample

[23] https://flipboard.com/@nylon/all-the-yeehaw-fashion-at-the-2020-grammys-ranked/a-E-SFmaj7QDS26Hhyad85OQ%3Aa%3A3195438-1305b8ee76%2Fnylon.com

[24] https://www.buzzfeed.com/tessafahey/lil-nas-x-tweets-before-famous

[25] https://power1051.iheart.com/content/2020-01-13-cardi-b-says-that-she-wants-to-go-back-to-school-become-a-politician/

[26] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p1ubTsrZFBU

[27] https://www.spin.com/2019/07/pete-buttigieg-lil-nas-x-old-town-road/

[28] https://reclaimpridenyc.org/

[29] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b8epyQ5MnFY

[30] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paris_Is_Burning_(film)

[31] https://www.okayplayer.com/

[32] https://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/sep/18/mykki-blanco-review-hip-hop

[33] http://www.bigfreedia.com/

[34] https://www.cakesdakilla.com/

[35] https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/music/story/2020-01-26/grammys-2020-fka-twigs-prince-tribute

[36] https://www.pride.com/comingout/2020/1/11/janelle-monae-casually-comes-out-nonbinary

[37] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Saul_Williams

[38] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RA0-9vM9ccE

Kate Doyle Griffiths is an anthropologist and organizer with the International Women’s Strike and Red Bloom in New York City.