Imagery

At the confluence of the internet age and the #MeToo movement, revisiting John Berger's book Ways of Seeing and its discussion of nakedness verses nudity is a conversation that needs to be had. Not only because he articulated the predominance of the male gaze and discussions of power, but because he referenced Walter Benjamin's Art in the Mechanical Age. Namely that, through reproduction, when art is removed from its intended location of contact with the public, it takes on different meanings through recontextualization, -- the intrinsic location of artwork lending some of the meaning overall (part of the psychological pilgrimage to approaching art).

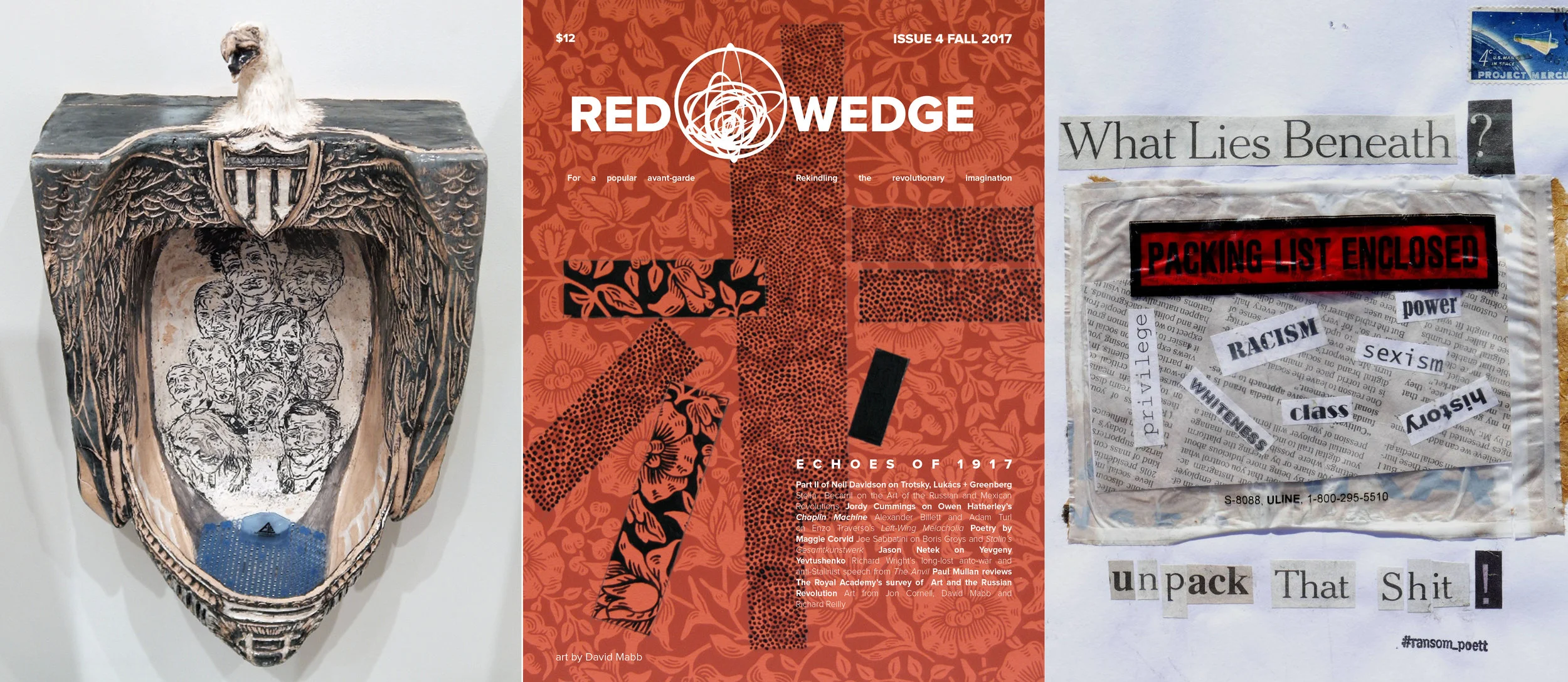

My decade-long engagement as a communist propagandist had convinced me of the importance of revisiting the old question of “political art,” and the linkages and gaps it opens up between the received notions of “aesthetics” and “politics.”

My work pivots from the following ideas and concerns:

Art was shamanistic in origin (under primitive communism).

The present day avant-garde is a “weak avant-garde” (see Boris Groys) detached from both the modernizing and utopian impulses of the modern avant-garde.

The solution to this weakness is a popular avant-garde that deals with the lives and concerns of the majority of the world (the working-class, the exploited and oppressed).

A viable strategy to combat the weak avant-garde is “narrative conceptualism;” putting the stories of working-class people up front in experimental artwork.

These pastiche posters portray the victories and transformations of cat-kind following a revolution that has overthrown all relations in which cat is a depraved, enslaved, abandoned or despised being. These repurposed propaganda posters attempt to capture the aesthetic energy and radical, transformative hope of the 20th century revolutions while criticizing the social order that they both replaced and created. The works attempt not to rewrite or document history but rather to create hopeful images of a world in which creatures have escaped the logic of history and point toward a real-possible future.

Artists today are also caught in the Neo-Liberal expectations of competitive self-promotion, which generally exclude the disabled, economically-disadvantaged, lower-classes, aging, female, gender and/or identity non-conforming. The expected commodification of an artist's work and life is profoundly alienating to anyone who doesn't fit, into either mainstream society or mainstream artists' societies. But there have to be spaces for all art; as there has to be a place at the table for all peoples, or it is no longer art (but an extension of imperialism).

These compositions are the latest in a growing body of work exploring connections between humans and nature in contemporary society. I work part time in the shipping department of a small company, and witness a surprisingly large amount of paper waste. As an artist, and avid environmentalist, I couldn’t bring myself to throw away the paper left behind from generating shipping labels. This paper contains a waxy coating, allowing the sticky label to be removed easily while preventing easy recycling. These mixed media works consist of photographs printed on those label backings.

My paintings are figments of fantastical imaginary worlds situated within realms, which allude to our own existence. The imagery I use comprises unravelling narratives, which display splayed visions and altered expressions of the world around us. Themes stemming from theological backgrounds have direct imagery taken from the Book of Genesis and the Book of Revelations.

I attempt to create a new space and time within the painting, asking the audience to question what they see and from where they are seeing it.

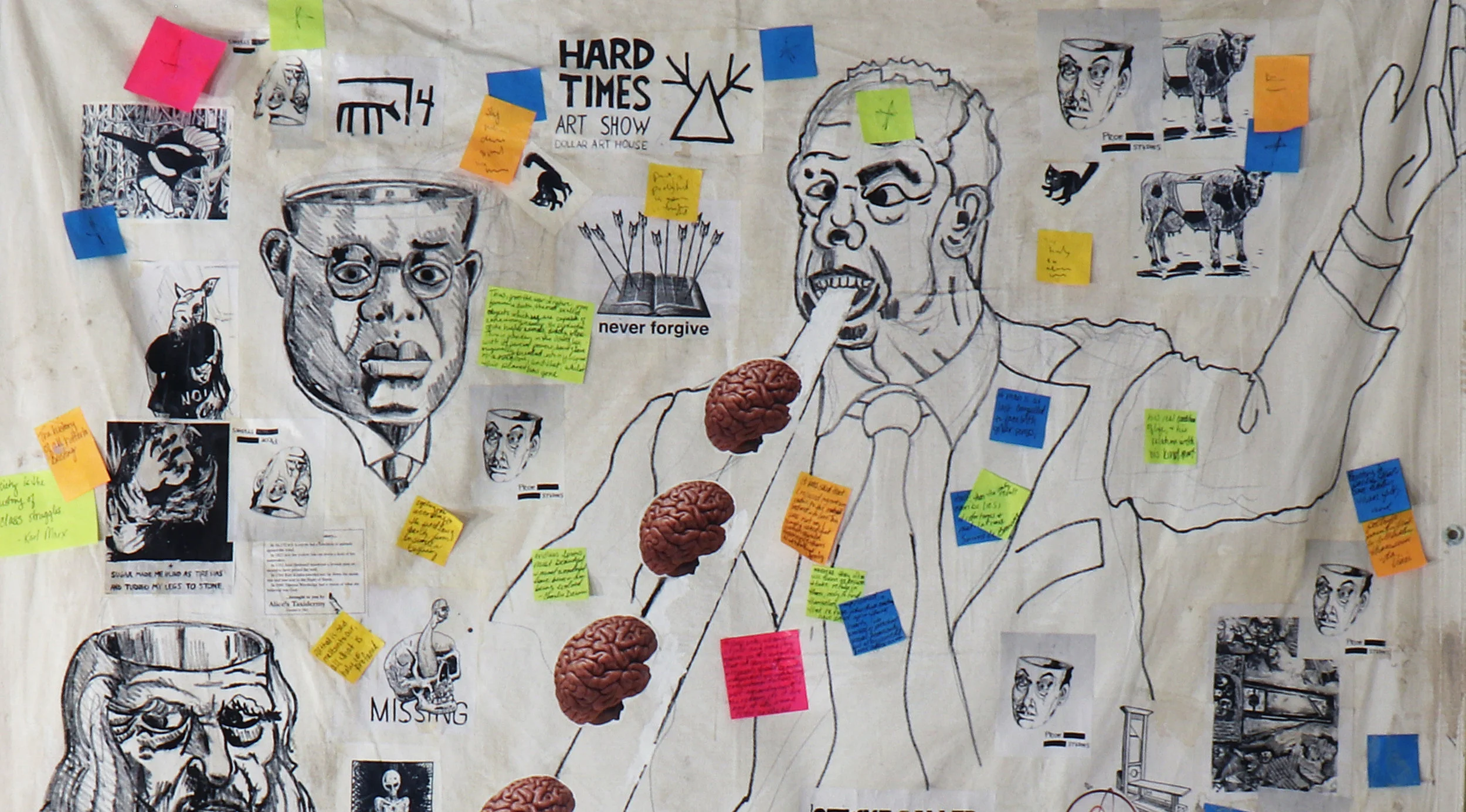

The following is an artist talk by Red Wedge's Adam Turl at the opening of his exhibition, The Barista Who Disappeared, at Artspace 304 on June 1, 2018 in the artist's home town of Carbondale, Illinois. This exhibition marks the last (for now) iteration of Turl's two-year project, The Barista Who Could See the Future, about a coffee shop worker and artist living in Southern Illinois who believes he has visions of the future. The city of Carbondale is facing a crisis as budget cuts and inflationary tuition hikes are undermining Southern Illinois University (the city's main employer) with the active hostility of the university's board.

The installation Long Live the New! Morris & Co. Hand Printed Wallpapers and K. Malevich’s Suprematism, Thirty Four Drawings, including covers, addendum and afterword is made from a combination of two books: a Morris & Co. wood block printed wallpaper pattern book from the 1970s containing 45 sample wallpaper designs by William Morris, the 19th Century English wallpaper, textile and book designer, poet, novelist and Communist; and the Russian artist and pioneer of abstraction Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematism, Thirty Four Drawings, published in 1920.

This video is part of Adam Turl's installation, The Barista Who Could See the Future, on display as part of the Exposure 19: Jumbled Time exhibition at Gallery 210 in St. Louis through December 2, 2017 (also featuring artists Lizzy Martinez and Stan Chisholm). The installation and short video “documentary” above center around the story of Alex Pullman – a coffee shop worker and artist who claimed he had visions of the future. A zine accompanying the installation, supposedly written by Pullman, reads as follows.

This group of paintings has a non-linear connection to events in Syria. I started using this particular form – oil on large wood panels – when Syria was still a relatively tranquil country. None of the iconography I arrived at through shifting oil and pigment presaged, referenced or interpreted any of the digital images that have found their way to comfortably horrified audiences in the West. Yet after five years of following the Syrian nightmare from afar, I cannot help but see Syrian tropes in all of these paintings...

If you wanted to understand my mother’s commitment to social change, I would start out with her belief, “We don’t become who we are in a vacuum; we are shaped by those around us and our experiences and time.” Born in 1909, Mary Perry Stone grew up in a family of seven in the small town of Jamestown, Rhode Island; she described her childhood as happy and developed a love of art from an early age.

When she was fifteen years old she worked for a summer for a very wealthy family in Newport, Rhode Island who said if she worked for them at their winter home in New York City, she could take art classes at the Art Students League. While the Art Students League experience made her want to continue to study art in New York City, she found the wealthy family shallow and backbiting; the person she admired most was the family’s kind chaperone and cook who had helped her.

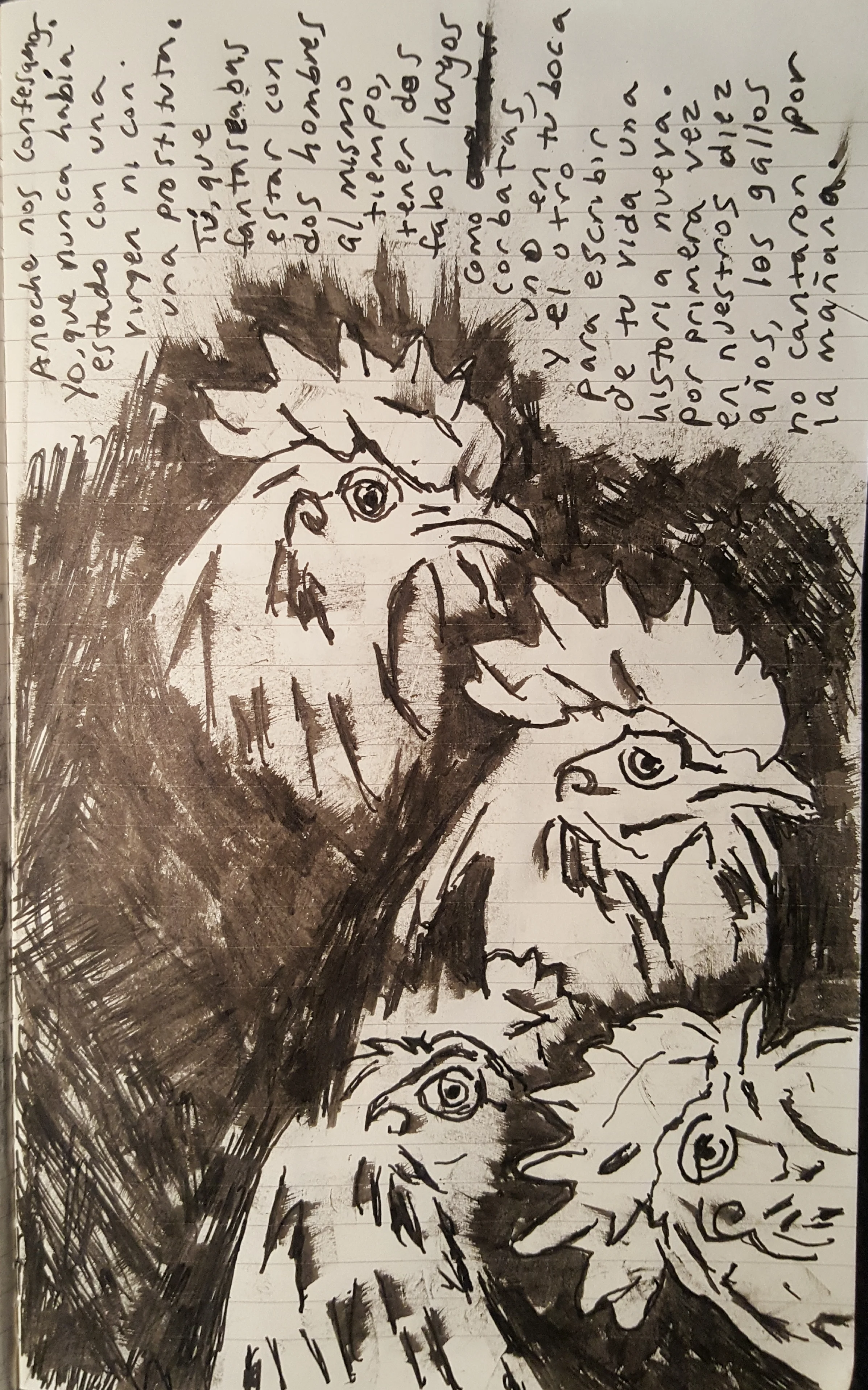

I have always believed that art and magic were the same thing. In magic, you can manifest power by manipulating objects. These objects (such as images, symbols, and signs) could be utilized to induce activity on the forces of nature and create different mystical phenomena.

This is the main reason why the majority of my works are expressionist ink sketches with figurative representation of resistance against capitalism, patriarchy, racism, imperialism, and other backward manifestations. I believe expressionism is a product of resistance against impressionism and academic art; an art movement charged by emotions, spirituality, and mysticism.

The Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) is leading a one-day strike on April 1st. In Illinois, leaders of both political parties have orchestrated an artificial budget crisis. Under the pretext of this false scarcity of resources people like Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel and Illinois Governor Bruce Rauner are firing teachers, closing schools, and wreaking havoc on public education.

Something particularly notable out this strike is that it is not just the CTU out there today. The strike is being billed as a call to action for entire city. This makes it unique.

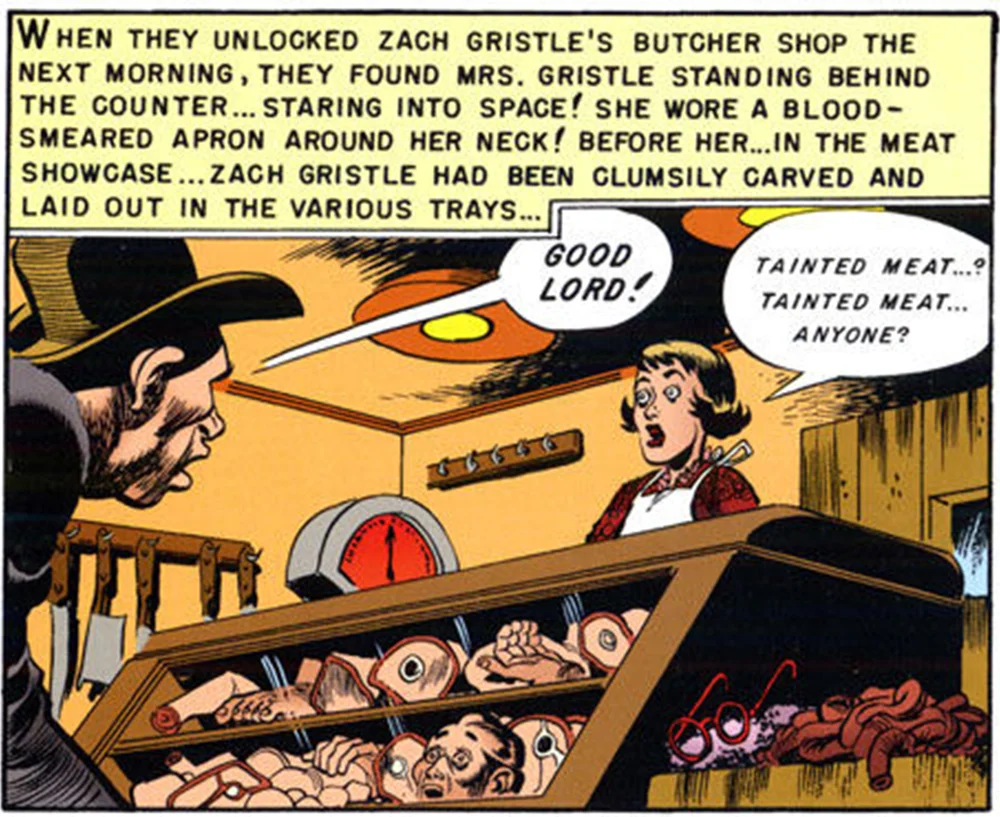

EC Comics (or Entertaining Comics), published a series of horror, crime, satire, science fiction and military comics in the 1940s and 1950s. These comics had a strong undercurrent of naturalism, echoing the novels of Emile Zola, albeit in fantastic circumstances (such as the Tales from the Crypt series). During a time of increasing political and cultural conformity EC Comics often struck a defiant tone, especially under the leadership of Al Feldstein, that echoed the Pop Front culture of the then recent past. That defiant tone frequently got the writers, editors and artists of EC Comics in trouble with the censors at the Comics Code Authority (CCA).

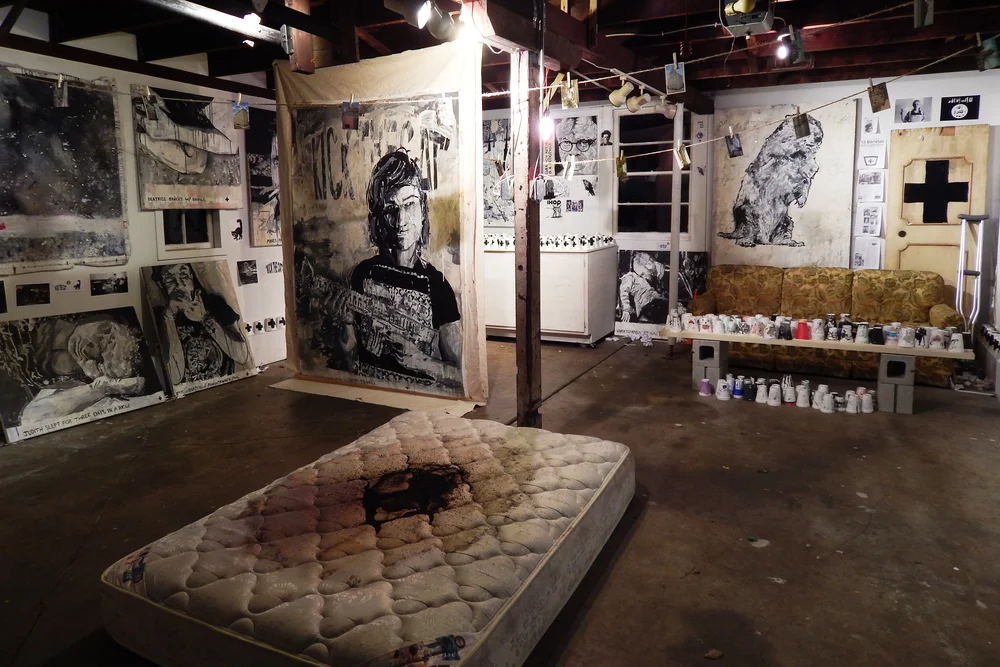

The following are images from an installation by Adam Turl at the Project 1612 art space in Peoria, Illinois. The installation tells the story of the artist Mary Hoagland, a Peoria native and former member of the 13 Baristas Art Collective, forced to move into her brother's garage after a serious car accident. The title comes from an exhibit Hoagland organized in her garage as well as the rank-and-file union newsletter produced by Caterpillar workers in the 1990s. In her paintings Mary tells fictionalized stories of the children and grandchildren of laid-off Cat workers and other residents of the greater Peoria area. This includes Kyle, who came to life fully grown when his father, a Fulton county sheriff, was cut in two with an ax; and a young Mary, who, in a bid to stop global warming, kidnaps Punxsutawney Phil so that he will never again see his own shadow.

About two weeks ago, a group of six of us from Syracuse joined other Black organizers, cultural workers, healers, etc. from all across the country for a weekend of national action in Ferguson. According to the organizers, “the Black Life Matters Ride was organized in the spirit of the early 1960s interstate Freedom Rides to end racial segregation.” Prior to going to Ferguson that weekend, like many other people, I could not take my eyes off of what was happening there. When my friend and colleague Sherri Williams, a PhD candidate and journalist asked if I wanted to, I gave a resounding “yes!”

We arrived in Ferguson on the Saturday of the nation-wide march. Even though I had seen the footage, the photos, read the reports, I still wasn’t sure what to expect when we arrived. We parked our van in a shopping center and then we walked down West Florissant, a main street in the city. As we walked to place where everyone was gathering to meet for the march, we passed by a number of boarded up storefronts with messages thanking The gray skies and clouds that hung low above our heads seemed to capture our collective state of grieving and mourning not just for Mike Brown, but for so many black folks that have been so violently killed and brutalized at the hands of the state.

The Chicago Women's Graphics Collective, much like the Chicago Women's Liberation Union and its Rock Band, is one of those neglected facets of the feminist movement in the 1970's. That is beginning to change with the release of films like She's Beautiful When She's Angry, as well as a broader interest being shown by a younger generation of feminists in their roots and history. The Graphics Collective created stunning work, some of which has found itself into the most well known iconographic annals of "the Long Sixties," even if its creators are far too infrequently acknowledged.

The text below is from Estelle Carol, a founding member of the CWGC. Still a feminist and socialist, she is now one half of the political cartoon duo Carol-Simpson, as well as a web designer in suburban Chicago. She also helps maintain the CWLU Herstory Project.