Manifesto

The following manifesto is the full text appearing in our “Issue Zero” pamphlet of the same title. Written during the spring of 2014, it maps out some basic thoughts shared by the editorial board of Red Wedge: the past rebellions within the worlds of art, music, literature, film and theater that have shaped our world, their current predicaments, and what we believe to be our role in facilitating a new, raw, urgent cultural expression simultaneously with a movement for radical social change. A digital version of this pamphlet can be purchased here.

* * *

The Thunder of New and Dangerous Myths

“We will smash the old world

Wildly

we will thunder

a new myth over the world.

We will trample the fence

of time beneath our feet.

We will make a musical scale

of the rainbow.

Roses and dreams

Debased by poets

will unfold

in a new light

for the delight of our eyes

the eyes of big children.

We will invent new roses

roses of capitals with petals of squares.”

– Vladimir Mayakovsky, 1919-1920

“Past one o'clock. You must have gone to bed.

The Milky Way streams silver through the night.

I'm in no hurry; with lightning telegrams

I have no cause to wake or trouble you.

And, as they say, the incident is closed.

Love's boat has smashed against the daily grind.

Now you and I are quits. Why bother then

To balance mutual sorrows, pains, and hurts.

Behold what quiet settles on the world.

Night wraps the sky in tribute from the stars.

In hours like these, one rises to address

The ages, history, and all creation.”

– Vladimir Mayakosky, 1930

* * *

These two poems, written a full decade apart, show us an author at his absolute height and at the lowest of lows. Vladimir Mayakovsky was a true artistic revolutionary. A troublemaker in the most literal sense, he was a writer who strove to make picking up a pen horrifying to “polite society.” In October 1917 the working-class in his native Russia overthrew the government and ushered in the world’s first workers’ revolution, Mayakovsky, like many other avant-garde writers, musicians and artists, was ecstatic (he was, after all, a Bolshevik). The first of these poems, “The 150,000,000,” reflected this revolutionary ardor.

Vladimir Mayakovsky.

The second poem was written in apparent despair. It was found following the revolutionary poet’s suicide. He was hardly the only one feeling such despair. Though the ruling bureaucracy of Josef Stalin claimed to be continuing the legacy of October, in reality it was the very opposite. It extinguished the leading lights of the world’s first proletarian revolution one by one in its dungeons and show trials.

The cultural renaissance of revolutionary Russia would be officially forgotten; displaced by the sterile banality of the so-called socialist realism. No longer were the boundaries of aesthetics to be challenged; instead they were to be employed as the window dressing of freedom for an exploitative regime. Some of Mayakovsky’s contemporaries followed his suit by taking their own lives. Others would end up kowtowing to Stalinism. A few, such as the revolutionary theater artist Vsevolod Meyerhold, disappeared into the gulags and were executed. Many would flee west.

Today’s cultural landscape markedly different in so many ways. Our planet has been reacquainted with the elation and despair of revolution and counter-revolution, but the nebulous indecisiveness of post-modernism still weighs like a painful muddy hangover on our culture.

For three decades we were told that history is over, that there is no such thing as society, and that therefore any attempt to revamp and start anew was bound to fail. Post-modernism was the “cultural ideology” (and echo) of the neoliberal economic and political turn (see Fredric Jameson, David Harvey and Ben Davis). As capital was “decentered” (but inexorably linked to the very real and concrete centers of financial power) so too was culture.

Just as our livelihoods and basic resources were stripped from us and privatized we were told that our culture was never ours to begin with. Culture could constantly move and change – be seen as entirely subjective and unknowable as a totality. Art and culture were just additional currencies to float, trade and accumulate – materially tied to wealth and ideologically wed to the lie that there was no alternative. Much like the globalization of production this post-modernization of art was facilitated by new technologies but driven by class interests.

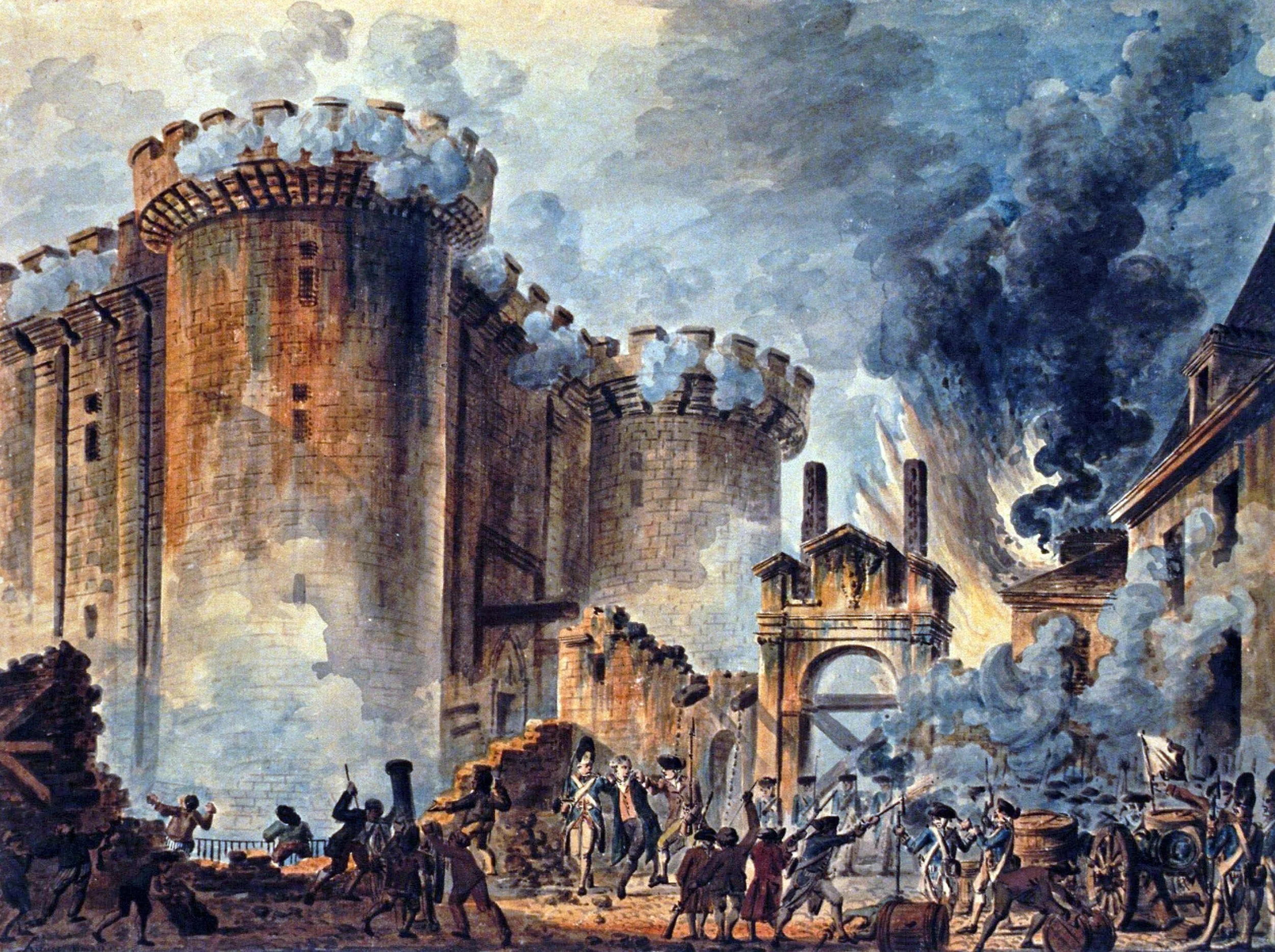

History has now returned with is its wars, economic crises, and the added specter of full-scale ecological collapse (an “end of history” that even the most cynical neoliberal could never conceive). As it has returned, it has destroyed post-modernism’s absurd relativism. But neoliberalism has soldiered on. “Serious” culture, high and low, has come to exist in an interregnum – neither storming its Bastilles nor celebrating its Versailles. To be sure, new Versailles come into being every day, whether it is the Crystal Bridges Museum built by Wal-Mart heiress Alice Walton or the new Guggenheim in Dubai, but we are ashamed of them. There have been battles on the streets, from Tahrir Square to Zuccotti Park, but the great prisons continue their operations. There has been a renaissance in Marxist letters among young radicals and intellectuals. Young artists are once again seeking to redefine what it means to create art connected to the world at large. The material basis for a socialist revival – both political and cultural – seems apparent in every major town and city. But just as the political continuity of the left was severed from its early 20th century high point, so too was its cultural continuity. The neoliberal imagination, with its “capitalist realism,” stunts the rebirth of a new cultural left.

Our History and Legacy

We have to re-stitch the fabric of our history and our contemporary efforts.

When the anti-capitalist artists of Western Europe fled to North America to escape fascism’s rise in the 1930’s and 40’s, they brought with them Surrealism’s gothic sensibility toward social revolution. This sensibility was infused into the ranks of the future American avant-garde – an avant-garde that was, at that very moment, taking to the streets to demand government support of the arts; mitigating the idea of art as a commodity and insisting that culture wasn’t a privilege but a right.

These artists looked east to the fleeing European masters, and to the south, to the heroic socialist murals of Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros. The plays of Bertolt Brecht were translated and performed. The greatest Black writers – Richard Wright, Hubert Harrison, Lorraine Hansberry – were communists. The best cultural thinkers understood that socialism was the antithesis of the unfolding horrors of privation and war. These were the highpoints of Marxism’s influence over art and culture, at least in Europe and North America: three decades of revolutionary hope, brutal immiseration, fascist despair and barbaric war.

There is also much to learn from the post-war decades and the cultural rebellions of the 1950’s, 60’s and 70’s against a (sexist and racist) consumer “utopia” that undermined the revolutionary purchase on the avant-garde. Unfortunately, too many of these rebellions turned inward. When the former Marxist Clement Greenberg put forward a monastic idea of the artist, it appealed to a generation that saw commercialism and consensus apparently triumph over privation and class conflict. A new process developed: Art slew its Oedipal daddies with increasing rapidity, ultimately producing a new signifying order – one in which anything and everything could be art.

When revolutionary hopes rose again with the generation of 1968, this process re-connected to anti-capitalist and revolutionary aspirations. The walls of a Paris gripped by general strike encouraged the people to “revolutionize everyday life.” National liberation movements saw culture as a key site of struggle as the works of Marquez, Kuti and Rostgaard reached the consciousness of Western radicals. The feminist movement’s insistence that the personal be regarded as political led to grassroots upheavals in galleries and concert halls.

But by the time the post-war liberal consensus collapsed in the late 1970’s, the flipside of culture’s self-awareness became apparent. The specialists of cultural studies were easily won over to the fiction that reality had no center: everything was merely a subjective representation of an unknowable existence in constant flux. Artistic expression mirrored a cynicism toward the recycled myths and tropes of popular culture. Literature was cut adrift into a morass of academic obscurantism and daytime talk show “book clubs.” The limited experimental space for music and film that existed in the 1970’s was progressively choked off. A consolidated and financialized industry imposed formulas on popular music; the line between mall muzak and “serious” sonic expression was all but erased. Punk and hip-hop rebelled, but these too were eventually metabolized. Art (high and low) entered a period of increasingly empty mannerism, reworking its histories and forms.

From the Ashes of the Old

This is not to say that there has not been great art -- or great political art. There has, but it is not yet animated and informed by the collective dream and science of a genuine alternative.

There are signs that culture may be awakening from its amnesiac haze. Just as the reality of dystopia must pervade our TV shows and movies, so must the possibility of utopia be raised. Performance artists and painters from Pussy Riot to Thomas Hirschhorn are asking what it means to produce their work in public in a way that doesn’t just shock the audience but seeks to engage. Questions of identity that have previously been straightjacketed thanks to the music industry’s segregation are now being used to test the boundaries of our future; it can be heard in the songs of M.I.A., Janelle Monae, and the burgeoning Afro-Punk movement. Cultural workers – from adjunct art history professors to museum handlers – have unionized. Artists, musicians and writers are heeding the call of Palestinians to honor the cultural boycott of Israeli apartheid.

There is no telling what the future may bring, but now is the time to imagine a new revolutionary cultural renaissance. In the final analysis, of course, such a renaissance depends on conditions beyond the realm of cultural production – in the realm of class struggle. But what are artists, writers and musicians to do in the here and now? We at Red Wedge believe we have some (dangerous) ideas.

We do not believe that art is a mere appendage of social struggle, or mainly as propaganda meant to facilitate (and be subordinate to) a particular class order, movement or ideology. But nor do we believe in “art for art’s sake.” There is great propagandistic art – Alexander Rodchenko and Emory Douglas both produced such art. There is also great art that is of no immediately apparent political significance. There is good and bad art of all political orientations – and all art reflects mixed consciousness.

Art is a semi-autonomous activity. As part of the social “superstructure,” art’s capitalist base constantly informs it (and vice-versa). At the same time art is more highly mediated than other aspects of the superstructure (for example, law). This is because art is shaped both by its peculiar prehistoric origins as a social and spiritual activity (see Ernst Fischer), and because art is a product of a social “sub-conscious” (the undercurrent of mixed consciousness: society’s libidinal wishes and fears, see Andre Breton and Walter Benjamin). Additionally all this is filtered through the artist’s own unique subjectivity and their own personal and class identities and relationships to society (see Leon Trotsky and Michael Lowy). Finally, like science, art has its own “laws” and history (see Trotsky) that artists respond to, even as art can be read by the logic of the society as a whole (see John Berger).

We can neither be agnostic on questions of artistic content and form, nor can we, as Marxists, take hard and fast programmatic positions on that content and form. There is a general crisis facing art, music, film and literature. It is born of the contradictions of art’s political economies, the cultural contradictions of post-crisis neoliberalism, and the separation of art and culture from everyday working-class life. History has returned but historical materialism – the method for understanding history – remains largely at the margins. Therefore, the main task for radical artists and cultural critics is three-fold:

- We must re-assert a revolutionary imagination, in both art and “real life,” cutting against the capitalist realism that continues to stunt culture in all its forms. First of all, this means re-establishing a Marxist art practice, Marxist art criticism and theory. We must excavate and introduce the history and traditions of past Marxist art practice, criticism and theory to a new generation. While it is not possible for artistic strategies to emancipate art – let alone society – radical art strategies must be developed. This will help us project the revolutionary imagination beyond the world of art as well as overcome the malaise of the culture industry. Art must begin, once more, to imagine the lines of its own emancipation. It must imagine what free art might be.

- Artists and cultural workers need to get organized. We need to organize around our ideas, but most importantly artists need to organize around our material interests. In the 1930s the Artists’ Union demanded relief and government sponsorship for the arts. For a few years the Federal government employed nearly 50,000 writers, artists, actors and musicians. Artists should not “starve” and art should not be a commodity. Per capita government art spending in the U.S., weighted to GDP, is one eighteenth government art spending in Germany. This is outrageous, and a byproduct of both capitalism and the particular vulgarity of the American bourgeoisie. Art should be produced for “the masses,” not a small layer of bourgeois and petit-bourgeois art patrons. Likewise, popular culture should not be distorted by the small mindedness and base greed of corporate producers. We must take organizational steps, beyond the mere attitude of our work, towards such goals.

- Art must connect itself to the exploited and oppressed both in content and in practical terms. Only the working-class can emancipate art through socialist revolution. Short of that, only an upsurge in class struggle and radical left organization will improve the conditions of art and cultural production. Moreover, art is a social enterprise. Art must be connected to the reality of people’s lives both in terms of its audience and content. Therefore art and artists, whether explicitly political or not, must connect to the struggles of the exploited and oppressed.

This does not mean that art must always and at all times be didactic. It does mean that artists should make common cause, on a personal and practical level, with the struggles of the exploited and oppressed. It also means that a Marxist understanding of social dynamics will produce better art -- especially when that art has significant narrative elements.

This is what Red Wedge aims to do as we prepare, in the coming months and years, to storm the still-standing bastilles and thunder new myths over the world.