Summer of 2013 at the Socialism conference in Chicago: Red Wedge editors at that time (left to right) Adam Turl, Crystal Stella Becerril, Alexander Billet, J. Matthew Camp, Nikeeta Slade and Brit Schulte

Red Wedge (RW) was started in 2012 by a group of (then) ISO (International Socialist Organization - US) comrades around Alexander Billet, Brit Schulte, Stella Becerril, and others. From the beginning there was a commitment to, tension and dialectic between, RW’s desire to play a modest role helping develop the actual production of socialist, left-wing, and working-class art, and its role reckoning on the socialist theory of art.

In terms of the latter goal, during the Socialism 2012 conference, Brit Schulte, Alexander Billet, and others became frustrated by the reductive manner in which many (but not all) comrades approached art and culture; often through the most immediate and practical political lens. Does this film, painting, novel, song, etc., immediately and plainly increase class consciousness, or consciousness around a particular issue? The classic Socialist Worker review would often end along the immortal (and largely useless) lines -- “and that’s why we must built the socialist alternative.” In this way many ISO comrades would look at foundational left-cultural artifacts – like George Romero’s zombie films – and read them primarily through a utilitarian lens. This would, for example, ignore the influence of French naturalism (Emile Zola) that was informed by the mass struggles of French workers, and its transmission into popular American culture through EC Comics (which published left oriented comics aimed at urban kids in the 1940s and 1950s). These comics, with antiwar and anti-racist messages, in titles like Tales from the Crypt, were read by working-class children, often the children of immigrants, at a time when such things could not be published far beyond the comic, noir, and pulp markets. The kids who read these comics included, tellingly, George Romero and Stephen King.

When comrades were aware things were more complicated in terms of a cultural artifact they would often invoke the most basic academic understanding of phenomena – say, the crude reading of Romanticism as mere reaction against the Enlightenment (and therefore on a separate, and ideologically hostile track from a true “Marxism”), etc. Walter Benjamin’s criticism of reductive “Marxist” art criticism comes to mind – “now swaggering, now scholastic.” Of course there many noteworthy exceptions. The legacy of the ISO in this matter, as in most, is contradictory.

The comrades who started RW wanted to take cultural theory more seriously. However, they did not want this theory to become detached from practice; either cultural practice or the practice of actual mass organizing. They did not want to recreate a detached academic cultural Marxism. In this way RW was born of the highly democratic impulse that culture and theory were things that can be mastered by working-class persons without “dumbing” them down.

In terms of the other goal, the creation of a clearinghouse for actual artistic/cultural production for a new generation of socialists, they were most immediately inspired by Occupy Wall Street and the Arab Spring. While the left was not strong enough to support the creation of a present-day network of John Reed Clubs, the creation of a left-cultural website was seen as a step toward something like that. The John Reed Clubs were the cultural salons organized by the US Communist Party (in Harlem, in Greenwich Village, in Hollywood, etc.) during the 1930s. RW editors were also inspired by publications like The New Masses that were associated with the John Reed Clubs.

The New Masses was itself inspired by the art and culture journal of the 1910s, The Masses, for which John Reed himself often wrote.

The early enthusiasm for RW’s project could be read, in part, as the byproduct of the ISO’s culture of cheerleading and tendency to exaggerate any new struggle. But Occupy was, of course, foundational to the current “new left.” The defeat of anarchist anti-politics helped produce the new socialist movement. Moreover, some members of the ISO Steering Committee (SC) were not entirely happy about the formation of RW. In private some RW editors were told by certain SC comrades that they should have asked permission before starting the project.

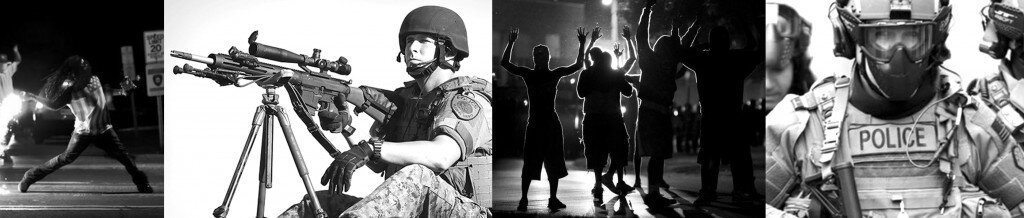

The retreat of the left after the defeat of the Arab Spring and the dissolution of Occupy, the stirrings of the new right in the Tea Party, and the birth of Black Lives Matter in Ferguson, Missouri, changed the logic of RW. Firstly, RW moved toward a more aggressively non-sectarian and ecumenical socialism. People from other currents began contributing to SW, including other Trotskyists, former (and current) Maoists, independent socialists, anarchists, feminists, etc. This helped move RW forward faster than the ISO itself on questions like sex work (in this regard Brit Schulte, and others, led the way) – as did the more bohemian milieu of cultural producers and artists. This helped inoculate RW against the pull of what we now call “normie socialism,” which existed (albeit not in full-normie form) in pockets of the old ISO. Secondly, theory seemed to become more important.

A Partial Pivot Toward History and Theory:

After Occupy and the Arab Spring

Around the initial waning of Occupy, Adam Turl came on board as an editor at RW (end of 2012/early 2013). Turl was, at the time, a suspect figure to part of the ISO leadership. But the RW editors brought Turl on despite that fact, and despite the fact he had picked a fairly big, but comradely, argument with an early RW post on Romanticism and the horror genre. Most of that debate is lost but one of Turl’s contributions is still online. In 2013, when Turl went public with criticisms of the ISO (signing the Socialist Outpost letter) he offered to resign from the RW editorial board. The other editors refused his resignation.

RW remained oriented on becoming a broad far-left cultural center – but delved deeper into theory and history, led in different directions, sometimes overlapping, by different comrades. This was true in cultural forms – music (largely focused on punk, Hip Hop and their descendants), visual art, literature, etc. It was also true in theoretical venues – feminism in Hip Hop, punk and pop music – particularly from Alex and Stella; Turl’s research into the origins of art (based on the Marxist art critic Ernst Fischer’s analyses of art and primitive communism) and gothic Marxism (inspired by China Mieville and others), the question of rhythm and the groove; contemporary art, historical encounters between popular and avant-garde art and the working-class, the left and movements of the oppressed. In addition, RW started a series of articles that were meant as educational introductions to some of this left-wing cultural history, in articles about Constructivism (including Jessica Allee’s article on textile work ); Emory Douglas, Punk, Dada, Hip Hop, Brechtian theater, Dario Fo, the art of the Federal Arts Project, the short stories of soviet author Isaac Babel, Egyptian surrealism, etc. We published a newly translated edition of the historic statement by the Paris Commune’s Federation of Artists. These pieces sometimes produced a number of debates. Adam Turl’s introduction to Dada provoked a debate with former RW editor and art historian Grant Mandarino. The original is no longer online but Grant’s polemic is here and Turl’s response is here. These were not widely circulated at the time because we were all taken aback by how sharp Grant and Turl’s polemics were. We usually took great pains to avoid sectarianism as well as overheated and disproportionate argument among comrades.

The First (and only) International Dada Fair in Berlin, 1920 (the most left wing iteration of the Dada movement/moment). It was shut down by the police and the artists arrested for insulting the German military.

At the same time, we maintained a commitment to be connected to, in solidarity with, and part of, actual mass struggles and contemporary politics. This was in addition to practical organizing work comrades were doing as individuals in Chicago and St. Louis. After the beating of sex worker and adult film actor Kristy Mack in 2014 we published “Labor Intensive: In Defense of Sex Work” by “A Dozen Pissed Off Sex Workers.” During the sustained two month stand-off between police and the people of Ferguson, Missouri (just outside St. Louis where Turl had moved in 2014), we organized a statement, “Artists and Writers in Solidarity with Ferguson” signed by dozens of artists and writers. After the Egyptian police murdered the poet Shaimaa El-Sabbagh we posted two of her poems (translated into English) on our site.

We also continued to post/publish art and poetry from comrades throughout this time. We even had a series of regularly updated blogs. Adam Turl posted art regularly, as did now former editor Hope Asya, and others. Jase Short wrote a socialist speculative fiction blog titled “The Ansible.” A favorite from Jase was his article on the “Theory and Appeal of Giant Monsters.” The art historian and critic Paul Mullan also wrote a blog for us at that time. Omnia Sol, coming onto the EC, edited a blog of RW commix.

During this time (2014-2015) we had a number of different editors, but the core editorial team was, arguably, Alexander Billet, Adam Turl, Brit Schulte (until about half-way through 2015) and Crystal Stella Becerril. It was also during this time that RW began to organize for left-wing and Marxist conferences, like the Left Forum in NYC (which we quickly discovered had been taken over by lunatics, periodic anti-Semites and worse) and the far better, of course, Historical Materialism conferences in London and Toronto. We also began, or increased, print publications, starting with “Issue Zero” of RW. This was a small pamphlet with the subtitle, “The Thunder of New and Dangerous Myths.” The subtitle was taken from a Mayakovsky poem -- “We will smash the old world / Wildly / we will thunder / a new myth over the world.”

Red Wedge zero (designed by Hope Asya)

Red Wedge one (designed by Hope Asya)

The text of issue zero is online here. Issue one and zero were both designed by Hope Asya.

The Turn to the Popular Avant-Garde:

Left Aesthetic Regroupment

In 2015 we started a six-month long (or so) discussion about the “perspectives” and ideological or theoretical orientation of RW. We had several formal discussions as well as many informal discussions. These culminated, led by Alexander Billet’s rediscovery of, and our collective elaboration on, the concept of the “popular avant-garde” in a reorientation of RW toward that idea, an increased focus on the print issues for RW (designed from issue 2 on largely by Adam Turl with Omnia Sol), and greater emphasis on our participation in the Historical Materialism conferences. This also led to Billet and Turl becoming co-editors-in-chief of the RW project (2016-2018).

RW 2 (cover art: Adam Turl)

RW 3 (cover art: Howard Barry)

RW pamphlet: Notes on the Popular Avant-Garde (cover art: Adam Turl)

RW 4 (cover art: David Mabb)

The concept of the Popular Avant-Garde wedded a commitment to the seemingly contradictory poles of “experimental” art and cultural production with a pre-occupation with the social, material and psychological needs of the exploited and oppressed. On the one hand the specific character of the experimentation was open. We did not declare ourselves, as a group, in sympathy with a particular aesthetic or conceptual strategy, but a particular constellation of contemporary and historic left-wing artistic strategies – left Romanticism, Russian Futurism, Dada, Surrealism, the Mexican Muralists, Brechtian theater, theater of the oppressed, punk and Hip Hop, Benjaminian criticism, situationism, salvagepunk, the contributions of China Mieville, Michael Lowy, etc. It was, in essence, a left-aesthetic regroupment orientation.

This reorientation was announced in a December 2015 post. This reorientation provoked the resignation of founding editor Brit Schulte from the editorial board. Our formal response can be found here.

In the spring of 2016 Omnia Sol, Alexander Billet, Crystal Stella Becerril and Adam Turl travelled to Toronto (in Omnia’s old car that had a stuffed skunk on the dashboard) for the Historical Materialism conference, at the strong urging of Jordy Cummings, who had started to be a regular contributer to the magazine and had a relationship with the Toronto HM organizing committee. We organized two panels.

Historical Materialism Toronto 2016, left to right: Alexander Billet, Adam Turl, Tish Kahle, Jordy Cummings

The first panel was titled, like the second print issue of RW, “Art Against Global Apartheid” and included presentations from Billet, Becerril and Turl. Audio online.

The second panel, “Interrogating Uneven and Combined Development” included presentations by Billet, Turl, RW fiction editor Trish Kahle, and Jordy, who came onto the RW editorial board the following year. The audio is online here.

Jordy’s entry onto the RW editorial board came after a series of pieces in 2015/16 on musicians and music, and in particular, how to engage RW’s theory of the Popular Avant Garde as applied to rock music as form. With near two decades of years of experience writing about music as well as Left politics, most recently as interventions editor at Alternate Routes, Jordy brough a more specifically music-focused role to the RW project,, exploring the politics of counterculture and social movements more broadly. This ‘defense of trangression’ from a firmly Marxist standpoint, as against “normie socialists” fed into later interventions on fascism. antisemitism and Islamophobia.. After well-received “anti-obituaries” for Ornete Coleman and David Bowie, Jordy’s music oriented engagement with RW began by engaging the debate between Perry Anderson and David Fernbach pertaining to formal vs. technical analysis of music. This debate played on the digital pages of the RW website, as did a feisty debate between Jordy and longtime RW comrade Bill Crane on Bob Dylan, with constant input from Alex, both on site and behind the scenes. Developing his own theory of sixties historiography or the “missed encounter,” Jordy’s long discussions with Alex were a vital part of this work.

Adam Turl, Alexander Billet, and Stella Becerril at Historical Materialism London 2016

In the fall of 2016 we organized a series of workshops at Historical Materialism London. The conference began the day after Donald Trump “won” the US presidential election and soon after the Brexit vote in the UK. Turl was in residency in Paris at the time. Becerril, Billet and Turl wrote the RW editorial on the election at the conference:

Stella Becerril and Adam Turl at Historical Materialism Toronto 2016

Alexander Billet and Adam Turl at Historical Materialism Toronto 2016

Stella Becerril, Alexander Billet, and Omnia Sol at Historical Materialism Toronto 2016.

Agatha Slupek speaking at a RW panel at Historical Materialism Montreal 2018

Tish Markley working the RW table at Historical Materialism Montreal 2018

Jason Netek and others in front of our Historical Materialism Montreal 2018 art installation.

Alex Billet speaking (HM Montreal 2018)

Holly Lewis speaking, with Neil Davidson (HM Montreal 2018)

Jordy Cummings speaking (HM Montreal 2018)

Adam Turl speaking (HM Montreal 2018)

In 2017, as we geared up to publish the third issue of RW, “Return of the Crowd,” meant to begin a quarterly publishing schedule (that we were never able to achieve), we made the following (fun to make but ridiculous) promotional video.

These years (2016-2018) were, in some ways, the most fruitful years for RW. We deepened our approach, we fostered new relationships, began networking with a far wider group (but still small) of Marxist artists, writers and cultural theorists – well-known, lesser-known, working-class, “professional,” and in-between. And we presented and organized workshops at a number of Historical Materialism conferences (in London, in Montreal, etc.) At the 2018 Montreal conference we were able to organize an art installation of various socialist artists and RW collaborators. During this period the EC was internationalized (partly) with editors from the UK (Joe Sabatini), Canada (Jordy Cummings), and briefly Australia (Cat Moir), serving.

Consumer Grade Film, In Circles

Over the years we posted and published interviews with dead prez, Stephanie McMillen), Oracle Productions (a left-wing theater group), the film collective Consumer Grade Film, Nicolas Lampert, the author of A People’s Art History of the United States, Michelle Cruz Gonzalez, Michael Lowy and dozens of others.

It is notable that we published and/or are continuing to publish multi-part series from Joe Sabatini, as well as the renowned theorist of Uneven and Combined Development, Neil Davidson. Joe’s work on romanticism, from the Tales of Hoffman, to foundational English synth pop attained a dialectical relationship with Davidson’s staggering tour-de-force on modernism, Lukacs, Trotsky and Clement Greenberg. The third and final part of Davidson’s trilogy appears in this issue. This coalescence between different yet related sensibilities helped deepen all of our perspective on balancing the visionary with the spectacle, taking a particular tangent from Walter Benjamin’s criticism – of maintaining or reasserting the “aura” of art beyond commodification.

In these years, we deepened our approach to a number of theoretical questions, culminating in Billet’s articles on neoliberalism’s arrhythmia in relationship to the city and music, Turl’s articles on aesthetic leveling, the “weak avant-garde,” gentrification and outsider art, Jordy’s articles on popular and experimental music, developing a theory of improvisation, recuperating countercultural figures like Bob Dylan and the Grateful Dead, etc. The latter fed directly into Jordy’s doctoral dissertation (and book, perhaps) in which Red Wedge’s perspective on the Popular Avant Garde is a central guiding point . We also continued our political-cultural interventions – albeit in a more developed way, with the article co- written by Billet and Turl on the Ghost Ship fire, and especially Jordy’s articles, particularly his polemic against “Normie Socialism” and Angela Nagle, as well as his interview with key RW comrade Kate Doyle Grifftihs. It was at this time we produced the fifth and sixth print issues of RW.

RW 5 (cover art by Adam Turl)

RW 6 (cover art by Anupam Roy)

From 2016 to 2018 RW moved forward in tandem with the rebirth of socialism (in the US with the growth of DSA) and the rebirth of left social democracy (in both the US and the UK). We had developed thousands of online readers and a hundred or so readers of the analog print edition. At the same time, Omnia and Turl started, in St. Louis, an art space called “Dollar Art House” that hosted, in addition to art shows, and socialist functions (mostly with the Socialist Alternative St. Louis branch, now an independent socialist formation in St. Louis), various RW events. Dollar Art House aimed to be an alternative space to the “weak avant-garde” (the phrase Turl borrowed from Boris Groys to describe contemporary institutional art) by promoting an overdetermined political but expressive art that tried to cultivate a socialist and working-class audience.

Artists Buzz Spector and Brandon Daniels at the Hard Times Art Show

Ashton Rome at the Dollar Art House.

Sara D’Lacy, Sunni Hutton, and others at the Dollar Art House.

Jesa Dior performing at the Hard Times Art Show. Artwork in background by Jon Cornell.

Dollar Art House

RW 3 Launch at the Luminary Gallery in St. Louis

Dollar Art House

Dollar Art House

Dollar Art House

Dollar Art House

Dollar Art House

Analog RW advertising St. Louis

During the 2017-2019 period, coming out of the very well-received polemic with regards to Angela Nagle, RW organically developed a perspective with regards to what became known, in issue six, as “defense of transgression.” In response to a backlash against counterculture, queer folks and cultural producers, a counter-narrative started to emerge which we did quite a bit to push, notably with our interview with Kate Doyle Griffiths, Adam Turl’s work, both written – “the working class is weird” – and visual. Nagle and Amber A’Lee Frost’s attacks on RW and Jordy Cummings in particular helped build RW’s affiliation with a layer of the queer Marxist left. Fighting queerphobia, transphobia and biphobia in particular, and social conservatism in general, has emerged as a key issue. This was a thematic link within our series of panels in Montreal, including a collaborative paper between Jordy Cummings and Kate Doyle-Griffiths (on counterculture and social reproduction), and informed the overall stance of our last print issue. Jordy Cummings, later to be joined by others, had become members of an emerging online (and increasingly offline or “Live”) salon, the Leftovers online discussion group. There was to be collaborative work between Leftovers and RW at HM New York, which due to events mentioned below, was not to take place, though one of our editors, Omnia Sol, did appear on a panel with Leftovers comrades. Jordy has to continued to be a participant and organizer of panels at the HM conferences with “Leftovers Live”, including this spring in Montreal.

Concurrent with the emergence of RWs Queer Countercultural turn, breaking with his colleagues, Jacobin editor Peter Frase wrote a well-received polemic on his personal website, “Keep Socialism Weird,” drawing on our transgression issue. There has been — or at least there had been — a noticeable shift in Jacobin’s content, away from a reductive and anti-countercultural approach. Frase’s pithy line had come to become one of our slogans that summed what had become our affirmative political perspective – to cultivate a popular avant-garde: a project to keep socialism weird.

Drawing by Adam Turl from RW 6.

RW’s last hurrah at the Historical Materialism conference came in London in November 2018. RW had three panels and an active presence as an entity, with our table adjacent to our comrades in RS21. On one panel, Alex and Adam spoke alongside the renowned artist and theorist of sexuality Shannon Bell, who presented a version of a paper published in RW six, with visuals of her sometimes quite daring artwork). Adam Turl, falling prey to influenza and two decades of social anxiety disorder, ended up producing a video instead of attending in person. This panel helped continue our internal and external debates on the politics of counterculture, a topic engaged by Jordy and Kate Doyle Griffiths at the Montreal conference. Another panel dedicated to music featured an early version of Joe’s work on English synth-pop, Crystal Stella Beceril, and once again, Neil Davidson on the politics of punk. Finally, a panel on cultural history had Jordy presenting research on the role of the western Left and counterculture, notably Allan Ginsberg and Lou Reed, and on the left opposition in “really existing socialism”. Rounding out the panel was the respected Iranian-Canadian journalist Arash Azizi and longtime RW contributor Toby Manning on the politics of the Beatles.

Shannon Bell (2018)

RW table in London (2018)

Jordy Cummings (2018)

Late 2018 into early 2019 had RW on a proverbial high, but that of course wouldn’t last…

Hard Times in Red Wedge Town

In 2019 the ISO collapsed. Like a lanced boil it spread poison across parts of the left. In this context current and former RW editors were the subject of online gossip that had a destabilizing effect to put it mildly. One editor who was subject to rumors had resigned a few months prior to their circulation, while another editor felt compelled to resign of their own volition, in the wake of public (and entirely unwarranted) attacks on their character. This practical crisis forced us to scale back the plans for our seventh print issue and put out, instead, a special online issue in May 2019. We will not comment further here on the cynical manipulation of vulnerable comrades, except to point out the eagerness to dispose of individual human beings (rightly or wrongly) is, in many ways, a reflection of how neoliberal capitalism sees individual working-class people as disposable and even irredeemable. The same logic applies whether it is a campaign to “cancel” an individual online, or through gossip and ostracization in real life. This is one way the new socialist left is internalizing the specifics of contemporary capitalism. The atomistic logic of the social industry permeates even our best offline spaces. This is contradictory, of course, because the social industry also provides an avenue of expression, however deformed, for those historically denied that expression.

Beyond this practical crisis, however, we found broader questions facing our project. The overarching strategy, as noted above, of RW’s first seven or so years, had been, more or less, left-aesthetic-regroupment. That strategy, while still important, is now insufficient. Globally, the fascist and far right threat has grown. In the United States socialism has gone from a notional to actual movement. Abstract questions have become increasingly concrete. What is true of politics and struggle in general is true of culture and aesthetics. We cannot pretend, as some do, to be agnostic on questions of design, cybernetics, the white cube, realism vs. irrealism, etc. It does not follow that debates on these questions need to be overly polemicized. We need to be comradely and patient with each other. However, the specificity of socialist-aesthetic strategy has become more important.

RW panel at the Left Coast Forum in Los Angeles in 2018 on “Art, Gentrification + The Right to the City” – left to right: Alexander Billet, Jason Netek, Megally Miranda-Alcazar and Adam Turl

The controversy regarding the Arnautoff murals in San Francisco; the fascist manipulation of irony and social media; the development of a minimalist aesthetic of technological fetishism that erases social context – and the importation of that aesthetic into the new socialist movement in certain organizations and publications; the complicity of social practice art and the weak avant-garde in gentrification; the increasing sophistication of capitalist realism in narrative arts; the ongoing debates about cultural appropriation and what Anupam Roy calls “the impossibility of representation;” what it means to make art at the possible “end of the world;” -- all raise a host of questions about left-aesthetic approaches that demand specific answers and specific approaches to cultural production. This does not mean that any of us are now opposed to artistic freedom, however partial and contingent it may be under capitalism. Nor does it mean a denigration of theory and speculative practice. It does mean that the question of praxis has become more important.

This begs the question of the future of the RW project.

Some of our current and former editors are now working on a new quarterly publication, Locust Review, that takes a critical irrealist approach to the production of socialist art and culture. LR is the first of many new projects that are emerging out of RW. As the editors write in the announcement for their first issue:

Locust Review will be unapologetically socialist and irrealist. We reject the framework of “capitalist realism” that has infected every aspect of our culture, producing cynical aesthetics and narratives, projecting the “morality” of exploitation into daily life as well as forward and backward through time. This “realism,” its constant viral imagery, its “prestige” television shows, its banality, tokenism and zombie formalism, is little more than an apologetics for social terror and the daily traumas inflicted on working and oppressed people.

We propose what we and other radical thinkers have called critical irrealism. Irrealism is a broad tradition encompassing horror, surrealism, fantasy, conceptualism, speculative fiction, situationism and many other “non-realist” styles and movements.

Critical irrealism emphasizes the alterity, the otherworldliness, of these styles to discover a radical truth living in the cracks of late capitalism. The surrealists might have called this the “dream image.” Indian communist artist Anupam Roy (featured in our first issue) calls it “the real image.” Whatever it might be called, we see it as corresponding more closely with how people experience and interact with a world at once hyper-connected and alienated while threatened with really-existing catastrophe.

Socialist Realism, in the contemporary context, tends to assume a non-existent “normal” working-class. The working-class is weird. There is no normal to appeal to. Critical irrealism assumes a working-class that contains within itself varied and queer multitudes. It assumes the gravediggers of capitalism to be a chaotic jumble. And that each individual gravedigger contains within them an entire universe.

Art from Locust Review. Art by Tish Markley + Adam Turl

Art from Locust Review. Art by Jon Cornell.

Art from Locust Review. Art by Adam Turl

Art from Locust Review. Art by Anupam Roy.

Other comrades are working on other projects and areas of research – aiming to gleam insight and practical action in newly developing contexts. For those editors in Canada and the United Kingdom, highly different political cultures than the United States, the context may well be less developed or coherent than in the United States, a happy surprise in a sense, albeit a frightening one for those living under Trumpism, but a moment of there being proverbially “just no space for a street fighting man”. Nevertheless, the cohering of the Left in the United States has raised the stakes in the coverage of aesthetics and their politics on an international scale. Witness the debates over films like The Irishman or The Joker, and compare the level they are conducted to older debates about “cultural appropriation”, memorably written about in RW by Stella. New journals on popular culture, music and film, even videogames may be in the works from those within the RW milieu and Jordy, along with others, is in the preparatory stages of launching Red Wedge-connected multimedia projects. Omnia Sol continues to break new ground as an artist and musician. Canadian comrades of RW at Upping the Anti as well as other small Canadian socialist and anarchist currents continue to support our work individually and collectively. Likewise, in the United Kingdom, Revolutionary Socialism in the 21st Century (RS21) are closely allied with current and former RW collective members and contributors.

Jordy Cummings and Alexander Billet at Historical Materialism London 2019.

Adam Turl, David Mabb, and Anupam Roy at Historical Materialism London 2019.

Anupam Roy and Tish Markley at the Museum Tavern in London (where Marx purportedly used to drink while writing Capital across the street in the British Museum).

Of course, then, there is Jacobin. Alex and Jordy have both written well received and popular pieces for this vital institution of the American Left. As noted, we are admirers and readers of Jacobin even if we sometimes strongly disagree with their content and design decisions. Some of us on our comrade Doug Henwood’s Left Business Observer list-serve (Leftbook before there was Leftbook!) witnessed the foundation and early development of Jacobin by young socialists like Bhaskar Sunkara, now well ensconced as Jacobin’s editor and publisher. Without Jacobin’s role in building a Left audience beyond “the usual suspects”, we suspect RW would not have had the impact it has had, and we are impressed with the vastly improved cultural coverage. We would like to maintain a relationship with Jacobin as an entity, as we do with Historical Materialism. Though without an official presence at the London 2019 flagship conference, several of our current and former editors and many more of our contributors presented there, RW (in some way, shape or form) is still planning to have a major presence at future conferences, including a full scale art installation in collaboration with Locust Review at the Montreal iteration.

Beyond HM, in our various capacities, we plan to plug our RW perspectives into ventures local to various members, and perhaps intervene at evens like Left Forum, Socialism and other such gatherings of the Left intelligentsia. We continue to support the work of newer or upcoming initiatives and publications of which there are far too many to name, and some have yet to launch. Through the flourishing of left journals, offline and online, a Left intelligentsia is finally being reconstituted; We see this project as that of a communist/revolutionary socialist/anarchist counter-intelligentsia there to work in and against the emergent social-democratic intelligentsia. Gauche de la Gauche, as it were

How this all fits into (or doesn’t fit into) the RW project we have yet to fully reckon.

To consider Red Wedge’s history from the post-Occupy ferment all the way to the global climate justice movement and struggle against right wing populism, it gives us pause to see how much we have learned and changed. This has come with the uneven but nonetheless genuine growth in interest in socialism, revolutionary or reformist, as well as the transformation of the DSA from old Cold War social democrats to the largest US-based left organization since the halcyon days of the CPUSA. What is clear to all of us now is that much of the Left now takes art and culture far more seriously and less reductively than it did in 2012. We no longer have to tell readers to take art seriously. Instead we are cultivating, in many forms, this exiting open sensibility, and in so doing, contributing to a rebuilding of what Alan Sears, a supporter of ours for some time, calls an “infrastructure of dissent.”

In the current moment, our editorial collective is significantly smaller than in the past, and less active. Yet we see it as our responsibility to keep the project going. As we recently informed our readers, after this issue, we are going back to a website model, with regular content, and we invite readers and longtime contributors alike to send submissions. In following our strong points from recent years ,RW will be increasingly focusing on political interventions, whether at HM conferences or other similar events, yet always from our standpoint of the Countercultural Left. Like the great Marxist cultural journals of the thirties, we won’t hesitate, as we have of late, in intervening in broader political questions. These questions will become all the more vital, depending on how the Sanders phenomenon shakes out.

Whatever else comes to pass, all of us, both current and former editors, remain dedicated to the project that animated RW for so long – the rebirth and development of socialist and working-class cultural production, and a popular avant-garde that anchors the poetry of life among the exploited and oppressed who make all poetry possible. The job of the artist and the critic is to shed light, but not to master, and we will continue to shed our proletarian light, and leave it on.

Written by current and former members of the Red Wedge editorial collective