Commentary

“Jews will not replace us”. This was the scream of the fascist hooligans marching with pitchforks last summer through Charlottesville. Their reference is to an all-American yet simultaneously ancient conspiracy theory- the idea that the Jews were conspiring to bring in immigrant populations, empower people of colour and of course, themselves, to “replace” an amorphous “white America”. This is the theory of “White genocide” that got the irascible George Ciccariello-Maher in shit with Drexel University. The very top of the ontological totem pole for this dangerous delusion are Jews.

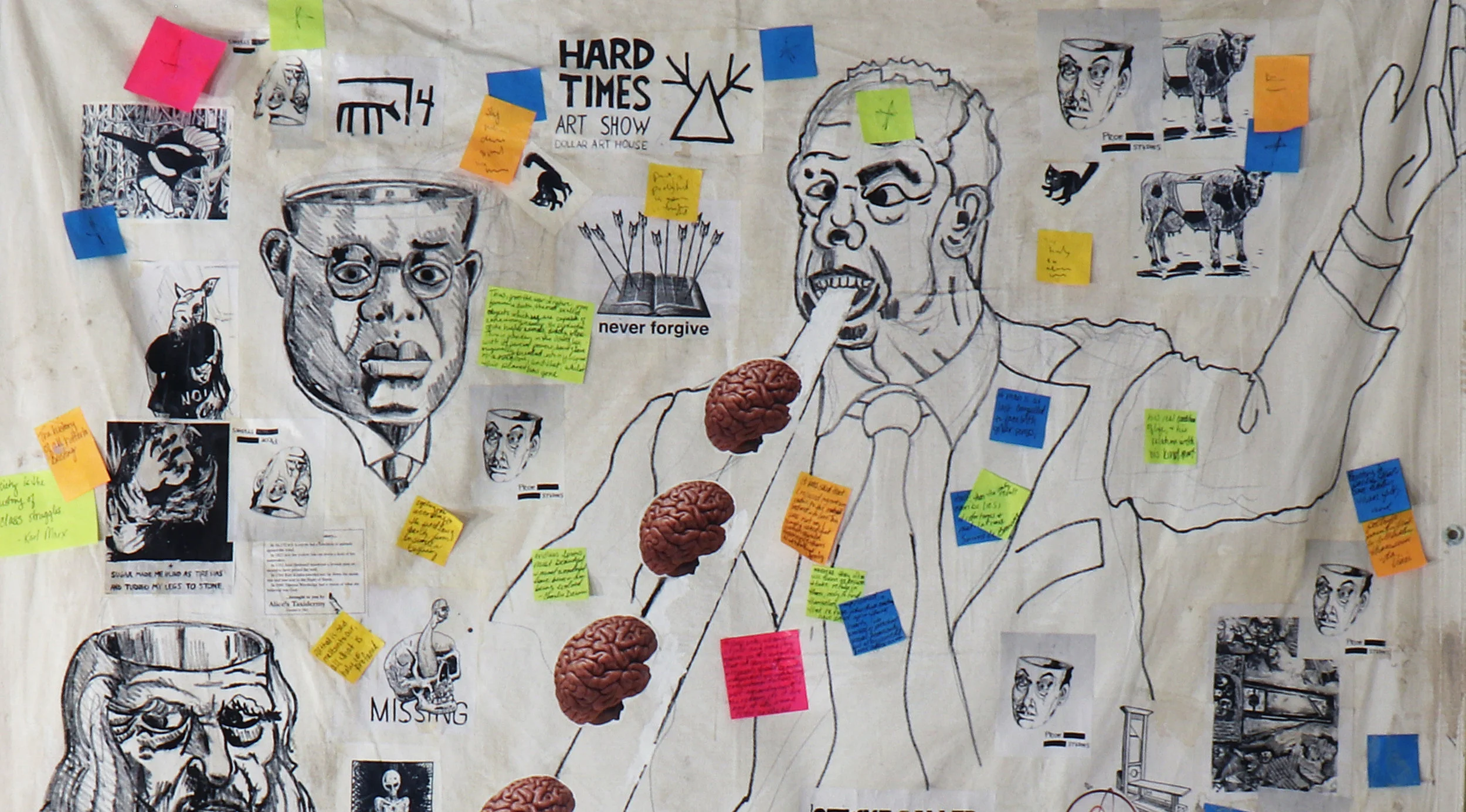

The following is an artist talk by Red Wedge's Adam Turl at the opening of his exhibition, The Barista Who Disappeared, at Artspace 304 on June 1, 2018 in the artist's home town of Carbondale, Illinois. This exhibition marks the last (for now) iteration of Turl's two-year project, The Barista Who Could See the Future, about a coffee shop worker and artist living in Southern Illinois who believes he has visions of the future. The city of Carbondale is facing a crisis as budget cuts and inflationary tuition hikes are undermining Southern Illinois University (the city's main employer) with the active hostility of the university's board.

Imagine, if you will, aliens, grey ones, with those big eyes, travelling through the universe and finding a capsule in the sky, representing the people from the planet Earth, a peaceful place (or so it looks from space). On the capsule, the aliens find a recording – it is “Johnny B. Goode”, the 1958 ur-narrative of rock music, Horatio Alger as channeled through the experience of Southern working class youth. “He never learned to read or write so well,” sings Chuck Berry, who died on Saturday at 90 years old, “but he could play his guitar just like-a-ringin’ a bell”. A sort of rock folk-tale, young Johnny can’t do much except play guitar.

The student butterfly that flapped its wings in Paris, May 1968 led to an earthquake which shook factory walls across western Europe in the 1970’s. Out of the dust emerged an ugly snarling rodent called punk rock.

The 1970s in the UK was a time of open conflict. Strike leaders sent to prison and then freed by a massive strike wave, teenagers fighting in the streets against each other, against the police and against the army in Ireland, miners strikes, power cuts, three day week, women battling for equal rights, Tory government brought down. The working class – loud, proud and winning.

“Heard joke once: Man goes to doctor. Says he's depressed. Says life seems harsh and cruel. Says he feels all alone in a threatening world where what lies ahead is vague and uncertain. Doctor says, ‘Treatment is simple. Great clown Pagliacci is in town tonight. Go and see him. That should pick you up.’ Man bursts into tears. Says, ‘But doctor... I am Pagliacci.’ Good joke. Everybody laugh. Roll on snare drum. Curtains." – Rorschach, Watchmen

It’s easy to say that it’s because of Halloween. But why this Halloween? Why not last year or the year before? Will 2016 (already an ignominious year) be remembered as the year that sent in the clowns?

Dario Fo, who died this past week, was a great playwright of the years of unrest and rebellion in the 1960s and ’70s. His plays such as Accidental Death of an Anarchist and Can’t Pay? Won’t Pay! were hilariously cutting critiques of life under capitalism as it went into crisis. His style of theatre was like a Brecht play performed by the Marx Brothers in the age of TV. They even became long running hits in London’s West End.

Brian Mulligan, a teacher, writer and performer who was part of the “alternative comedy” scene of the 1980-90s, said...

The artist behind Zeal and Ardor isn’t American. He’s Swiss, albeit of African heritage. Manuel Gagneux was prompted to begin the project by a 4Chan post. In an interview with Noisey’s Kim Kelly, he claims that he used the message boards as a starting point for his own musical experiments:

I used to make these threads where I would ask for musical genres, one would post “swing,” and the other would post “hardcore gabber techno” and I’d fuse the two and make a song out of it in 30 minutes. One day someone said “n*gger music,” and the other said “black metal.” I didn’t make the song then, but it stuck with me, and I thought it was an interesting idea.

What can be said about the Grateful Dead that has not been said before? They are on one hand somewhere below Coldplay and Nickelback on the list of hatred-objects for Leftists of who came of age between the late 80s and late 90s, signifying affluent Frat Kids tripping balls and hacky sacking, earnest liberals reading Sean Wilentz and taking bong hits, and so on and so forth. On the other hand, they were an emblem of a very particular milieu at a certain period...

This text begins with facts, they will not be argued here. We live in a police state founded on white supremacy. Philando Castile has been murdered along with thousands of others for being black. For white supremacy blackness is both a necessary other and its greatest threat.

Any analysis of what Diamond Reynolds did when she livestreamed the aftermath of Philando Castile’s murder will be incomplete and totally insufficient to meet the demands of her call for justice. “Truth makes a hole in knowledge.”

In the face of profound social, political and economic tragedy, it has often been the case that popular musicians, out of a sense of solidarity, put out a song to capture the moment and inspire the movement. It is often the case, by virtue of historic specificity, that these songs don’t date well, their universality caught in the particularity of a given moment. There are a few songs, however, that have outlasted their origins and continue to resonate. Neil Young’s “Ohio,” Bruce Springsteen’s “American Skin (41 Shots)” and, most recently, in the face of the spate of police murder of Black youth, and in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, Prince’s “Baltimore.”

Reminiscent of mid-period Prince and the Revolution, it combines a funkish shuffle in a minor key with vaguely country/western sounding acoustic and electric guitars. The lyrics, while angry, are more sad and resigned than anything else...

Yes, there were Dada women!

One hundred years of Dada this year. Cabaret Voltaire lasted less than six months from its opening, February 1916 in Zurich, Switzerland. Who would have guessed that its obscure beginning would herald a world-rocking negativity that was at the same time an ardent demand for renewal?

The group, idea, movement that it created, Dada, itself didn’t last very long but quickly mutated into surrealism and somehow made its radical presence known worldwide.

There is no getting around the popularity or cultural clout that both Afropunk and Afrofuturism have in contemporary culture. It’s been over ten years since James Spooner’s film on Afropunk came out, the website that bears its name is visited by hundreds of thousands each month, and the yearly festival recently expanded from Brooklyn to Atlanta and will soon be making its way to Paris. Afrofuturism, for its part, has become quite trendy in certain circles, with advertising companies attempting to cash in on its aesthetic. It is not difficult to see its influence in a growing array of artists.

This is NOT an obituary. Indeed this article was written on Friday Jan 8th and Saturday Jan 9th. It is clear now that the meaning of "Lazarus" on the new record cannot be reduced to the Thin White Duke persona, though it is clear that, of all of his personae, Bowie felt most comfortable staging his death – his final work of art – using the persona of the dying, emaciated mid-seventies iteration of his chameleon-like ch-ch-ch-changes. The very act of planning an album release – including a tremendously disturbing music video of a very sick Bowie – around one’s death seems of a piece with Bowie’s lifelong artistic project…

A properly executed horror film establishes a strong connection between a fantastic element and plot devices which resonate with the audience’s social context. Usually these fantasy elements — whether they be ghostly, monstrous, or all-too-human — overshadow the social context of the narrative. Without this social resonance audiences have little reason to perceive the fantastic elements as objects of anxiety and fear.

The contemporary situation is defined by decades of a hyper-competitive culture combined with crushing economic austerity, a toxic brew which has produced an ever-growing crisis of anomie, or social atomization and breakdown. Mass shootings, once exceptional events, have “somehow become normal,” to paraphrase President Obama. In the midst of this, social forms which once served as vehicles to fight these conditions have either been coopted or crushed underfoot, leading people without any recourse but to seek individual solutions to social problems.

Chief Keef, a Chicago-born rapper notable for his hit “Don’t Like” and his bizarrely-named child, was already embroiled in controversy. The powerful Chicago drill scene arguably rode to national prominence on his back. His lyrics are profane and frequently violent. His debut album was released on Gucci Mane’s aptly named 1017 Brick Squad label when Keef was only 17. A minor spouting gunplay and cocaine fairy tales over music designed to send power surges through the synapses: cue the indignation.

Even with all that manufactured controversy, you could be excused for not knowing quite how to react to the news that Chief Keef’s concert, benefitting the families of a child and a member of his crew who were both killed during a Chicago drive-by, was shut down by the police after one song despite Keef only appearing as a hologram.

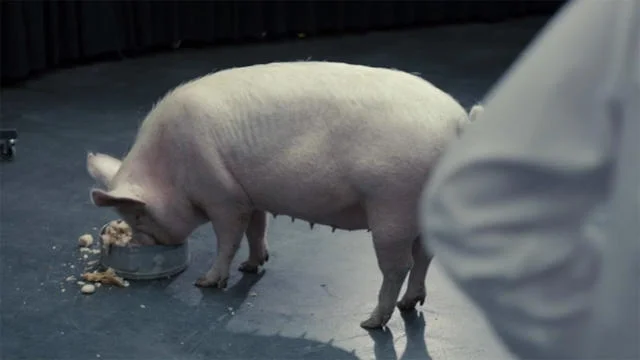

To hell with Banksy. The truly visionary artist of British pop culture is Charlie Brooker.

The iconic anonymous artist’s massive Dismaland project closed within days of an unauthorized biography's claim that British Prime Minister David Cameron once put his privates in the mouth of a dead pig during his time at Oxford. By itself, the incident would have been hilarious enough and would have certainly sent the UK tabloids into a tizzy. But the revelations regarding Cameron were made all the more tantalizing and just straight up weird by their proximity to Charlie Brooker’s Twilight Zone for the 21st century Black Mirror.

It’s been a year since the death of Michael Brown, a year since the rebellion in Ferguson, a year since the Black Lives Matter movement began to shift the conversation in just about every avenue of American life. That shift can be seen in politics (from #BowDownBernie to Donald Trump’s threats to beat up protesters) and economics (the Black Youth Project’s embrace of the Fight for 15). It can also be seen, perhaps most obviously, in our culture — and in music, in particular.

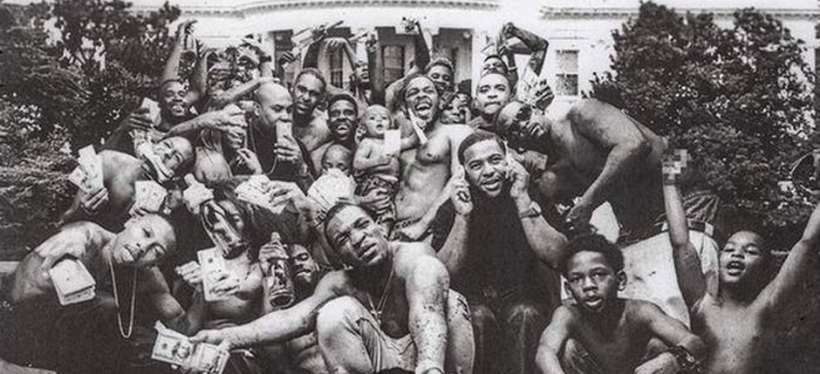

If the grand conversation around race were to be neatly divided into “before” and “after” Ferguson, then Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly would have to be regarded as something of an artistic landmark, a stunning musical distillation of the post-Ferguson mood. I am inclined to agree with Rolling Stone’s Greg Tate when he writes: “Thanks to D'Angelo's Black Messiah and Kendrick Lamar's To Pimp a Butterfly, 2015 will be remembered as the year radical Black politics and for-real Black music resurged in tandem to converge on the nation's pop mainstream.”

Lamar’s album has far exceeded all expectations. In its first day of release, To Pimp a Butterfly became the mostheavily-streamed album in Spotify’s history, racking up a reported 9.6 million listens on that day alone. It’s the first hip-hop or R&B album since Beyoncé to spend multiple weeks on top of the Billboard charts, and has already been certified Gold.

Black Future Month is here.

Black Future Month is the name film curator Floyd Webb and I selected as the title for our February Afrofuturism film series each Thursday at the SMG Chatham Theater in Chicago. Situated in the Chatham neighborhood on the Southside of Chicago, Floyd and I, as creators of Afrofuturism849, aimed to introduce curious audiences to the range of sci fi works and documentaries highlighting ideas, stories and people within the sci fi, speculative fiction, and science worlds. We showcased the Cameroonian film Les Saignantes about women in a corrupt mystical and futuristic Cameroon. We showed “White Scripts, Black Supermen” on the early black comic heroes and brought out Turtel Onli, father of the Black Age in Comics, comic creator Jiba Molei Anderson and Institute of Comic Studies cofounder Stanford Carpenter to discuss the project. Amir George, co-curator of the Black Radical Imagination, a series of experimental shorts introduced his works and several physicists and astronomers were on hand to discuss our science documentaries. While displaying my book Rayla 2212, a story that follows a war strategist on a former earth colony 200 years into the future who time/astral travels, one attendee remarked that she had no idea that black sci-fi and comics existed.

Paul Kantner was not the leader of Jefferson Airplane, the sixties band that came to epitomize the counterculture. Leadership rotated, original leader Marty Balin once joked, to whichever member was currently involved with Grace Slick. Neither was Kantner Jefferson Airplane or 70s Jefferson Starship’s lead vocalist, being only one of four singers, his warm, understated vocals often eclipsed by Slick and Balin’s more attention-grabbing turns. Nor was Kantner his bands’ primary songwriter – one of the Airplane’s four primary songwriters, he was just one hand on the Jefferson Starship overcrowded deck. All this is not however to bury Kantner – that occurred, literally, in January 2016, at age 74 – it is absolutely to praise him. Indeed to praise him in the most comradely fashion: as a key component in a countercultural collective, the very antithesis of the individualist diva.