Dorehedoro ✦ 2020 ✦ Available now on Netflix ✦ 12 Episodes ✦ 24 minutes

“In nova fert animus mutatas dicere formas corpora…

My mind is bent to tell of bodies changed into new forms.” - Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book I, lines 1–2.

Avant-gardists and transgressives, rejoice!

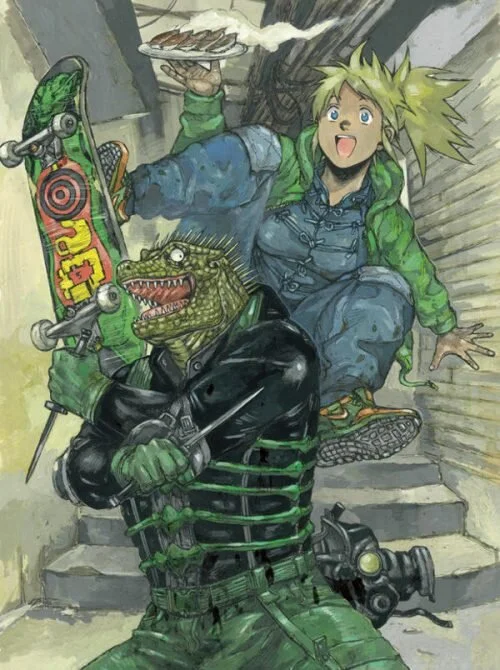

Netflix has delivered the official US release of Dorohedoro, the anime rendition of a 23 volume modern manga classic. The story is about an amnesiac man and his friend’s quest to regain his memory and identity back after having his head transformed into that of a lizard, by a sorcerer overlord whose identity is also a mystery. The backdrop is a robustly detailed dystopian world made up not only of our greatest nightmares, but also the horrors of a present reality. Dorohedoro is a tale that tests the limits of our grotesque imaginations.

Despite the copious amounts of wanton violence, blood and gore, Dorohedoro is not about life and death. It is about an existence in-between. The series is propelled instead by transformation, a changing of being, and metamorphosis. In fact, it toys with life and death in such a way that permanent death becomes an illusion, and what looks like death is the fodder of everyday life. It’s the kind of mind bending story-telling that shows signs of Franz Kafka is a literary influence.

Whether intentional on the author's part or not, it’s impossible to read Kafka, particularly his well-known novella The Metamorphosis, and not think of him when watching this anime. It falls neatly into the main character Gregor’s transformation, only backwards. It’s not just the slow becoming found in The Metamorphosis that is the subject of Dorohedoro, but the unbecoming. In that sense, it may help to think of this series as more of a spiritual sequel. There is even a character that seems to fit the description of a redeemed Gregor Samsa himself—a roach/beetle-like victim of transformation magic named “Jonson”—easily becoming the most lovable character.

The show is gorgeous, from top-to-bottom. The color palette is vibrant and diverse, but earthy and bold. The art-style is scratchy and rough, but detailed and robust. If you’re able to make it through 12 episodes for the eye candy alone, then read no further, as Dorohedoro’s value on mute is something that can stand on its own. Again, the show really shows its huge imaginative capacity here. There is not a single frame that feels like it is lacking. Anime watchers are used to seeing the deadline crunch in the popular studios deliver disappointing work, this show has the feeling of passion. CGI is used, but not in a way as to depict additional realism, flash or simply to make animation work easier. Instead, the animators use CGI in a more unorthodox way, where the technique is meant to stand out, break rules, not easily fit in. Basically, everything is the opposite to how most anime use CGI.

I’m a fan of the rigor contained in series like Dorohedoro. While typical Shonen series are deep in my heart, the 500+ episode weekly format of many of them is not what you’re going to find. No single fight outwears its welcome. The series moves fast. The backgrounds melt and morph between scenes like the paint on the wall of an LSD-inspired misadventure around your apartment. The show is detail oriented; miss a second, and you will not know where you are. It reminds those of us who fell in love with anime via movies like Akira or series like Cowboy Bebop—what is it that had us begging our grandparents to let us rent 3 x 3 Eyes at the now extinct Blockbuster Video? The production brings to mind the golden-years run of the Gonzo Studio series in the early-to-mid 2000s. Most series were short, around 25 episode averages and many shorter than that, with a clear production style that favored quality over quantity.

The dub (yes, I appreciate the range of them) and music are good as well, perhaps nothing to write home about, but tolerable when some anime has a tendency to drop the ball. The Netflix version comes with about a half dozen dub and sub options, and I have a tendency to go back and forth. While some series are indeed better in Japanese with English subtitles, with a clear preference for the Japanese voice actors, Dorohedoro is such a visual masterpiece that those who do not know Japanese may want to watch with dubs their first time around.

Into the Hole: Post-Industrial Alienation

“... just as early industrial capitalism moved the focus of existence from being to having, post-industrial culture has moved that focus from having to appearing.” - Guy Debord

I hated Kafka when I first read The Metamorphosis. I did not see the ending coming, unlike some of my classmates, and found it to be anti-climatic. Some part of me didn’t want to admit that the world, beneath appearances, can be a cold, dark place (for now). Kafka uses the book to bring to the surface the things beneath illusions that we don’t want to admit. I read the book more as intended than how many did, the translation didn’t specify “insect” as some did, but described the translation as “vermin”, and I didn’t perceive his transformation as anything particularly inhuman, and perhaps that shaped its effect on me, he might as well have been a leper. Regardless, I was naive and got my ass kicked by The Metamorphosis, foolishly feeling entitled to a redemption on the part of Gregor Samsa. Obviously, this would rob the book of its unique meaning.

The class society of Dorohedoro unfolds over time. The state of humanity is the worst of all beings, crammed into a precarious slum-realm known as the “hole”, under constant terror of the sorcerers, who thrive off humanity’s pain. The sorcerer’s realm has its own class society, with a wide gap in standard of living between the rich and powerful magic users, and those who may struggle with magic and as a result, live a life not unlike those of the hole. The sorcerers are dominated by another class, the mysterious Devils. The worlds collide in the most chaotic and destructive ways imaginable, the series somehow manages to conceive of a world that looks like our own, spiraling out of control and into absurdity.

Alienation is at the heart of both Kafka’s and Marx’s analysis, and Dorohedoro carries this torch. This phenomenon is when our labor is estranged from our product, work and relations with other humans. While there may be exceptions to individuals, it is important to us that we are passionate about our activities and the creative outcome, it is also important in our relation to others. The quest at the center of this show is a rejection of this alienation; the protagonist Kaiman is driven towards self-discovery in the most literal sense. This is exciting and central to the plot, because it’s an easy goal to identify with. In a world of alienated labor, we are all trying to discover ourselves, find our heads and get out of “the Hole”.

Dorohedoro takes place in a world (amongst others) where everyone has a mask, where people’s disguises say a lot about who they really are. Everything that happens is bad, and you’re constantly reminded that things can get worse. Nothing is as it appears, and nothing you see can be trusted. Marx reminds us that the taste of the porridge does not tell you who grew the oats. Appearances like this are present in Kafka’s work as well; the unconditional love of Gregor Samsa’s family is not even surface level by the end of the book.

What is Kafka’s subject Gregor Samsa’s main concern upon learning of his transformation? Getting to work on time. Without a thought, he puts his office job above his very well-being. The post-industrial dystopia of Dorohedoro likely has some behind-the-scenes bureaucracy. Bureaucracy is the farce that follows tragedy. It flourishes and thrives in the fallout and defeat of previous cycles of struggle. Kafka’s analysis of the alienation of bureaucracy flows throughout his work. It doesn’t translate into the show directly, but it’s almost implied by context, given the robustly detailed dystopian world that is built in the series.

How distant can the things we do be from who we are? For Marx, only so far, as one has everything to do with the other. Human essence is a constantly changing thing, and the question itself is at the heart of our very existence, according to many of Marx’s admirers, such as Jean Paul Sartre.

Metamorphoses of the Proletariat

“Labour is a condition of human existence which is independent of all forms of society; it is an eternal natural necessity which mediates the metabolism between man and nature, and therefore human life itself” Marx, Das Kapital, Chapter 1 Section 1

Without spoiling too much, the end of this season of Dorohedoro convinces me that its beauty is hidden in the common quest for humanity amongst the protagonists, distinguishing them from the very likeable villains. This drive for a return to the human form comes from all different angles, experiences and motivations, which give each character in Kaiman’s entourage their own place.

There is something Marxist about the concept of searching for humanity, the drive to discover and embrace human species-consciousness. Marx had the novel belief in a humanity able to change the conditions of its being, that is, there is no universal human nature beyond a tendency to recreate it. There is something all too human about the quest to become human. In Dorohedoro this is very literal, as this is the protagonist's main quest. However, questioning humanity and our own existence is something that most can relate to, and acting on the conclusions of such questioning has major consequences in human history. To put it simply, what it means to be human is not static, but dynamic. There is no such transhistorical human nature to speak of besides the phenomenal tendency to become something else.

What happens to our labor, in revolutions? For Marx, our labor is the everlasting Nature-imposed condition of human existence, however the form this nature takes is not universal throughout history. We can think of nothing less than a period of mass labor unrest, where we rebel against the commodity-form of labor, and transform it into something that overcomes it.

I would like to think of revolution as a metamorphosis of the proletariat, the unbecoming of a class-in-itself for a class-for-itself, the transformation of our labor from its commodity form into a form aligned with an advancing humanity, the overcoming of this world for a new one; a new world, where every worker wakes up with joy, eager to design the world of our freedom, rather than worry about getting to work late when you’ve been transformed into vermin. We need to turn the Gregor Samsas of the world into Kaiman.

Conclusion:

“He is terribly afraid of dying because he hasn’t yet lived.” - Franz Kafka, The Metamorphosis

Overall, Dorohedoro’s short but dense first season leaves us longing for more. As alluding to before, this is because we see ourselves in Kaiman’s quest for his own humanity. As dark and defeating as the show may feel at times, there’s this affirmation of our own quests and journey as human beings. This is its strongest point, although heavily supplemented by its artistic beauty and fun characters.

The show isn’t quite perfect; the fights, which are short and sweet, might be refreshing but I wonder if the stick was bent back too far in this case. The show also reveals the mysteries of the Dorohedoro universe at a rate that may have your attention swaying, even if the pace overall is very good. At the same time, you can easily lose your place watching it, because things change and shift so much in the wackiest ways. I also think some of the philosophical undertones were easier to decipher, but you can’t blame a good storyteller for that. Also, while I did not mind the CGI and decent (but nothing to write home about) dub, I can see why this may have annoyed fans. I have not read the manga, however I have heard mixed (from good to disappointed) feedback from those who have.

Overall, the series so far in season 1 is a strong 9/10, leaning towards 9.5 for me. It is fun, creative, visually pleasing, thought provoking and a refreshing reminder of everything that got me looking to anime for great stories and art so many years ago. Fans of everything from FLCL to Beserk will find something here. For fans of Marx, Kafka, and a myriad of others, you will find hints of speculative thought that will have your mind moving quickly. Is the dark world of Dorohedoro like where we are headed towards? What does metamorphosis, alienation, dignity and fulfillment tell us about the humanity of today, and the humanity we can become tomorrow?

Gus Breslauer is a gay space communist from Houston, Texas who writes about shame, gay politics, HIV/AIDS, and capitalism.