Interviews

I’ve been following the work of Indian artist, propagandist, and comrade, Anupam Roy, since early 2018 – after his work was included in the New Museum Triennial, “Songs for Sabotage” in New York. I sought Roy out after reading a review of the exhibition, “How the New Museum’s Triennial Sabotages Its Own Revolutionary Mission,” by the Marxist art critic Ben Davis. Davis is perhaps best known among North American socialists as the author of the (very useful) 9.5 Theses on Art and Class. I felt the approach Davis took to Roy’s work, however, was oddly cursory — almost dismissive. Davis seemed, in this review, to misrepresent the dynamic between art and politics and the character of Roy’s work, even as he was trying to make a more or less correct argument against the art world’s cult of ambiguity. I was particularly interested in Roy’s work as his emphasis on the concept of “excess” (Georges Bataille) is similar, in some ways, to my approach to the concept of “differentiated totality.” In April, Roy and I talked over Skype about his artwork, ideas and politics. That conversation was transcribed by myself and Tish Markley, and then edited by myself and Anupam for publication here. — Adam Turl, May 6, 2019.

Red Wedge spoke with one of our close comrades and collaborators, Kate Doyle Griffiths, for what was initially to be a discussion of transgressive social practices within the context of the West Virginia uprising. What transpired, however, was a wide-ranging discussion of transgression and Left politics, social reproduction theory, Insane Clown Posse and of course, the cultural practices of the striking workers in West Virginia, the polysemic quality of Twisted Sister. The following interview was conducted in June and July 2018. It will featured in our upcoming sixth issue, which you can subscribe to by supporting us through the Red Wedge Patreon.

The term “critical irrealism,” though present and well-known in the spheres of literary and arts scholarship, is unfamiliar to most. But then, so is living in the world of 2018. It is also alienating and in constant violent flux. Which means perhaps there is something for this critical irrealism to teach us…

Michael Löwy has written about critical irrealism – along with realism, Surrealism, Situationism, Romanticism and a great many other aesthetic approaches. He is the author of many books on a wide array of topics written from a Marxist perspective, from liberation theology to uneven and combined development, from Che Guevara to Walter Benjamin and Franz Kafka.

Much analysis of modern music focuses on lyrical content, but how can we understand modern musical forms? What relation do they have to the capitalist world in which they’ve developed? To answer these questions Kate Bradley interviewed Mark Abel, author of Groove: An Aesthetic of Measured Time.

Kate Bradley: Is it fair to say that Groove is a defence of popular music from a Marxist perspective? Could you summarise your argument in brief?

Mark Abel: It is a defence of popular music, but in the first place it is an attempt to explain why the music of our time sounds the way it does.

At some point or another, every artist ponders their purpose. Do they matter? To whom and in what way? What does it even mean to be relevant? And as the world changes quickly, will their art, their music, their words, continue to have an impact?

Algiers consciously ask these questions of themselves, and are constantly aware that doing so both is and requires a struggle. One of the things that makes them such a notable act is that their consciousness of this both ideologically and structurally.

Welcome to Dumpster Pizza Party: a podcast about art and DIY counter-culture with your host Craig E. Ross...

My guest today is VHS Girl, as known as the artist and tape-head Katie Winchester. In this podcast we discuss VHS Girl’s artistic journey from VHS collecting to creating paintings of her favorite VHS covers and becoming heavily involved in the DIY outsider art world. We also discuss the Solar Eclipse Comic-Con in Carbondale, IL that we both had the pleasure of participating in as well as movies, breakfast food, nerd culture, and the history of resistance against the KKK.

Joe Sabatini and Jordy Cummings of Red Wedge spoke with the Winnipeg-based cultural theorist Matthew Flisfeder and had an exchange on Flisfeder’s recent book, Postmodern Theory and Blade Runner, excerpted earlier this month on this site. Flisfeder’s insights transcend the analysis of a single film, rather he offers us new tools with which to engage the popular avant-garde, as well as how we can periodize modernity and postmodernity. A wide-ranging thinker and supple theorist, Red Wedge encourages our readers to seek out his exemplary cultural analysis. We look forward to what comes next from Dr. Flisfeder.

George A. Romero is dead. And much as some of us would like it, the director of the most iconic zombie horror films of late capitalism will not be rising from the grave to walk among us. But the ravenous consumption that we see in his creations – of flesh, of our sanity, of our hope for the future – will continue. Unless it is brought to its knees then late capitalism has all but assured this.

The interview below with author and film studies professor Tony Williams – one of the very first articles to appear at Red Wedge – was conducted by editor Adam Turl and appeared on the site in October, 2012.

Musician and socialist Dave Randall’s Sound System: The Political Power of Music was released to positive reviews in May. Randall, a veteran musician who has worked with Faithless, Sinead O’Connor and Emiliana Torrini among others, examines in the book music’s many uses and abuses from the perspective of both a practitioner and a serious Marxist. Here, Red Wedge republishes an interview conducted with Randall by rs21’s Colin Revolting on the book, its inspiration, some of its highlights, and how a radical movement can subtly but actively approach popular music.

My guests today are two of the editors of Red Wedge Magazine, Alex Billet and Adam Turl. Listen as we discuss the upcoming changes to Red Wedge Magazine as well as art, politics, Marxism, and the popular avant-garde. This show was recorded while getting a delicious brunch at Milque Toast Bar in St. Louis, MO. I’ll never be able to afford a house now after the delectable avocado toast I ate during the recording of this podcast

Shirin Rastin is an Iranian-born artist based in Orange County, California. She is exhibiting her latest series, Forced Entry, at the Dollar Art House in St. Louis, Missouri. The exhibition opens on Friday, March 24. The Dollar Art House interviewed her about her work before the exhibition opening.

Dollar Art House: In this series you combine commercial puzzles with puzzles you’ve made using images from the news media. In particular these include puzzles that show an idyllic “western” or “American” life (the former) and puzzles that depict the ongoing refugee crisis (the latter). Can you tell us something about how you arrived at this concept?

Stephanie Dinges is a working-class socialist, artist and activist running as a Green Party candidate for alderperson in the 13th ward of St. Louis. Dinges is running against a largely absentee pro-corporate law-and-order Democrat. On March 7th the aldermanic and mayoral primary was held in St. Louis. The general election takes place on April 4th. Red Wedge’s Adam Turl interviewed Stephanie about her campaign in late February.

Consumer Grade Film is a U.S. Midwestern collective of filmmakers focusing on low-budget, socially-conscious films. Their current projects include the short film Ubercreep, the feature film In Circles and the YouTube channel VHS Girl.In Circles tells the story of three teenagers, Carmen, Stephen, and Virgil, who "sell stolen prescription drugs in order to pay for an abortion, while the small farm town they live in is being threatened by a drilling company." Ubercreep tells the story of two women who are stalked by a driver from a ride sharing service. In late August Red Wedge’s Adam Turl spoke to Consumer Grade Film founders Carson Cates and Andrew Laudone.

Jesa Dior Brooks is a musician and artist. Their work positions the individual experiences of anti-racist and anti-capitalist struggle in an art historical context. They are part of the “Afropunk” duo Thee Mistakes and a member of the band Meathorse. Brooks will be performing and participating in the inaugural exhibition of the Dollar Art House, “The Hard Times Art Show,” on September 30 in St. Louis. I interviewed them in the lead-up to the event.

Capitalism, contrary to really any architectural experience, is not concerned with memory or with nostalgia or with remembering anything at all. Rather, capitalism is out to expand and reconfigure its gains, to exploit and, as you say, disavow. It forgets, and it forgets purposefully in order to expand further, and in its forgetting there is a bleaching forgiveness that is so total and permanent that it is negating in its testimony.

Can America ever truly face its racism – both past and present – for what it truly is? Or is the history of forced migration, bondage and slave labor, legal apartheid, incarceration and horrific state violence too much for it to survive such a revelation? Can it endure the psychic shock and endeavor in some kind of pursuit of truth or reconciliation? Or will it simply implode, come apart at the seams and make way for something new? Something which, hopefully, would not have genocide running through its veins? Langston Hughes tells of a man urging us to “let America be America again,” but Hughes is not so sure such an America ever existed. Neither should anyone today.

Michelle Cruz Gonzales (then known as Todd) played drums and wrote lyrics in Spitboy, one of the most important hardcore bands of the 1990s. Along with bands such as Grimple, Econochrist, and Paxton Quigley they were part of an explicitly political corner of the East Bay punk scene. With an all woman line-up Spitboy’s performances defied expectations of what “women and rock” and “feminism” were supposed to mean at the time. Gonzales’ new book Spitboy Rule: Tales of a Xicana in a Female Punk Band (PM Press) defies expectations once again. People of Color have been part of the punk scene from the beginning. Gonzales is part of a lineage that includes Detroit’s Death, The Bags (Los Angeles), Poly Styrene and Pat Smear. Spitboy Rule makes the invisible visible. It is both a walk down counter culture’s memory lane as well as a serious exploration of identity, gender and race.

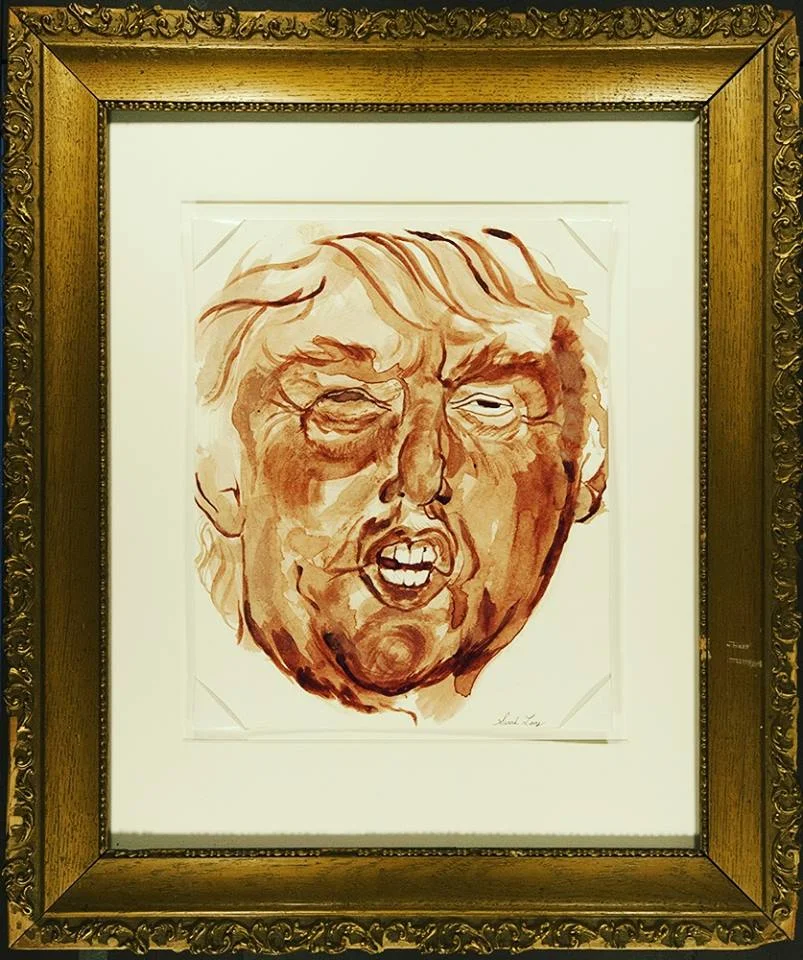

If there were ever a walking, talking, bloviating illustration of the American political tragicomedy, it is Donald Trump. The man who very well may win the Republican nomination for president due to his bottomless cash reserves is, for roughly the same reason, given carte blanche to say more or less whatever he wants under the guise of "it's what everyone is thinking." It bears pointing out that very few of his comments or platforms are "what everyone is thinking." A more apt description might be "what the anxious and insecure white male middle class is thinking."

This is likely why the art of Sarah Levy went so phenomenally viral during the month of September. The socialist, feminist and artist's rendition of the duck-faced one was a clever inversion of his words about Fox News' Megyn Kelly's menstrual cycle.

One could be easily forgiven for believing that theater is indeed “dead.” Every medium of culture and creativity struggles with issues of relevance and vitality, but the common conception of theater in particular seems to be one that has been most flagrantly geared merely toward parting tourists with their money. Of course, it’s not entirely true; the reality is far more complex. But the fact remains that there appears to be a gap between what we learn the live performing arts once were (or could be) and their present anodyne state. How is a play supposed to be relevant to working people? How can it be when it costs an arm and a leg just to go to one?

What does it mean to be “unrapeable?” It can mean, among other, almost limitless possibilities, that the labor we perform, the industry we work within, those that consume the products of our labor, and those that try desperately to deprive of us self-determined working conditions, somehow belongs to everyone but us. It means that our bodies are meant for others. It means we are robbed of control over our art and our labor, which are ultimately the same. To be “unrapeable” is to presume nymphomania. It means consent is rendered irrelevant. It devalues our bodies, our art, and our labor to the point of only ever being (to the chauvinist) in service of male desire.