Essays

The marginalization and removal of Bernie Sanders in the Democratic Party primary has once again proven that the party is inherently hostile to its working-class “base.” Thousands across the country are rightly concluding that we need our own independent socialist working class party. But how should we go about furthering this break? There are those who preach imprudent patience. There are comrades who argue that we have to wait for objective conditions to ripen further. There are those who argue against a “premature break” with the Democratic Party. And there are many more who are simply uncertain about how to proceed. Reaching this point during a devastating pandemic and economic crisis further complicates but underlines the urgency of this discussion. The following is in no way conclusive but is meant as a contribution against bleak passivity.

We are beset on all sides by disturbances of what the ancient poet-philosopher Lucretius called “an alien sky.” The Covid-19 pandemic is felt by all of us as a presence, a presence of that which should not, which cannot be—inasmuch as our ordinary perceptions define what can and cannot be. It sticks out like a sore, a wound, sudden and without warning causing even the bravest and strongest to groan. Our lives were moving right along, certainly already beset by intrusions into a billion little homeostases, when suddenly it all came crashing down. Before horror, we have felt a fascination with the very strangeness of it all, this thing which should not be that has arrived on our doorstep.

When is a virus more than a virus? There is one virus, the novel coronavirus that is leaving thousands of dead in its wake. This is the physical virus at the base of the bigger crisis now emerging across the globe. The other virus is more abstract. It is the effect of this pandemic on human populations, on bodies, on selves, dissolved into the abyss of mortality. It is the social virus, the virus disrupting the social and economic system in which we live and move and have our being. It is virus-as-crisis, the limits of the system of social relations now being tested to their breaking point. It is manifested in the chaotic events of each day, when hospitals are overwhelmed, normal life is disrupted by social distancing, and the stock market crashes in a drama dwarfing 1929. This is the broader crisis, the Crisis. The one which defines the entirety of our lives and the future of our species. It is a crisis of capitalism as a set of social property relations, as a means of governing populations, as a means of determining what is and is not meaningful.

Yet “toxicity” is not a floating signifier. In the era of Covid-19 and anxious preppers, virus metaphors having become part of the everyday parlance of information technology with its disposability of human beings through the logic of the social industry. “Toxicity,” on one hand, could be shorn of meaning. On the other hand, it can be seen as going beyond de-humanization in order to render a human being as a walking contagion…

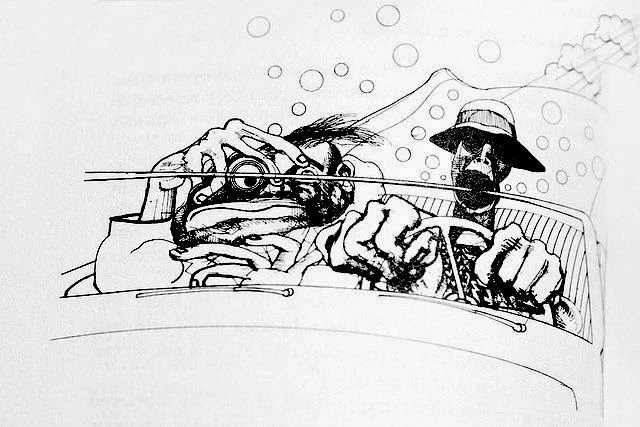

The default cultural logic of neoliberalism and the political center is capitalist realism. In response the cultural logic of working-class emancipation (socialism) is critical irrealism. The ir – or no – of critical irealism is opposed to a particular kind of realism. Therefore, we should examine it more closely.

In the age of Spotification, music has been decommodified in appearance. Of course even at the height of commodification it retained its use value “aura”; its metaphysical subtleties and theological niceties have always/already been there. But it is now a time in which music serves a different social purpose. In a sense, to play on Marx’s “collective labourer”, there is an emergent “collective listener”, predicated upon th

At the confluence of the internet age and the #MeToo movement, revisiting John Berger's book Ways of Seeing and its discussion of nakedness verses nudity is a conversation that needs to be had. Not only because he articulated the predominance of the male gaze and discussions of power, but because he referenced Walter Benjamin's Art in the Mechanical Age. Namely that, through reproduction, when art is removed from its intended location of contact with the public, it takes on different meanings through recontextualization, -- the intrinsic location of artwork lending some of the meaning overall (part of the psychological pilgrimage to approaching art).

In an October 2017 piece “How We Ended Up in the Golden Age of Horror Movies”, Scott Meslow notes that the history of horror films has been one of keeping the lights on in Hollywood while receiving no respect from the studios. Director Mike Flanagan recalls endless “eye rolls” at pitch meetings from executives who balked at any attempt to make a serious film in the horror genre—capital’s representatives wanted the equivalent of fast food with “empty calories” making up the bulk of their horror repertoire. What then explains this change of heart in recent years, with studios churning out critically acclaimed films such as Get Out (2017) and Hereditary (2018)? The most immediate cause is to be found in smaller studios producing critically-acclaimed box office hits with minuscule budgets—an attractive model in the era of $100 million dollar blockbusters.

In particular, I am concerned here to refocus away from the hitherto ‘ghostly’ character of Trotsky’s presence in this article to date and allow him to speak in the same way as Lukacs and Greenberg on their respective themes in parts 1 and 2. In particular, I want to introduce Trotsky’s concept - virtually unknown during the historical debates surveyed in Parts 1 and 2 - which he called “the ‘law’ of uneven and combined development”(UCD), the current widespread deployment of which has done so much to revive and consolidate Trotsky’s reputation as an important Marxist theorist, in addition to that of revolutionary strategist.

Lil Nas X burst onto the music scene--in retrospect, an inevitable star--with the Tik-Tok viral single Old Town Road in xx 2019. The song reached number-one status on Billboard 100 and occupied the position for 19 weeks, the longest of any number-one hit in sixty-one years.

In the 1992 science fiction film The Lawnmower Man, a mentally challenged groundskeeper named Jobe becomes hyper-intelligent though experimental virtual reality treatments. As his intellect evolves, he develops telepathic and telekinetic abilities. By the end of the movie, Jobe transforms into pure energy, no longer requiring his physical form and completely merging with the virtual realm, claiming that his “birth cry will be the sound of every phone on this planet ringing in unison.”

What if the global economy were structured, not to send wealth into the hands of a tiny group of oligarchs, but rather to ensure the best possible lives for everyone, ensuring that people lived fulfilling lives free from want, engaged in activities that interested them and engaged them, enabling them to pursue their own interests alongside working for the common good? What if people worked in co-operatives, coordinated together to meet the needs of society, organized from below rather than from above, with the workers themselves as the beneficiaries of their labor? What if the global economy elevated workers instead of immiserating them?

n the perma-retro that constitutes contemporary life, the 80s is a montage from Wall Street (1987) St Elmo’s Fire (1985) and Desperately Seeking Susan (1985): a sequence of wet-gel, shoulder pads and designer suits backed by bombastically upbeat music. Even 80s revisits like Wolf of Wall Street (2013) and Black Mirror’s San Junipero (2016) don’t go far from the format. We don’t often speak of right-wing utopianism – more of its “cold stream” realism – but the enduring fantasies of the 80s exemplified just that. For all both Wall Street and Wolf of Wall Street’s acknowledgement of 80s’ corruption, cruelty and volatility, it is the class-A rush of acquisition, consumption and social contract-busting that stays with the viewer. And the same is true of book and film of Bonfire of the Vanities and even American Psycho.

Though the notion of cursing sundials seems quaint today, these lamentations, attributed to the Roman playwright Plautus, speak to an anxiety about the draining nature of time measurement that still seems prescient. In 1967, over two centuries after Plautus died, the Marxist historian E.P. Thompson would take time out of the hands of poets and put it into the hands of historians and anthropologists with his essay “Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism” where he traced the relation of “clock-time” through the emergence of waged labour in the industrial revolution:

Social media asserts a massive multi-subjectivity. This is a conundrum for those who aimed to speak to/on behalf of the masses (for good or ill). It is a disaster for those who thought that without overdetermined capitalist media the masses would embrace their own emancipation, beauty and pathos. Storming Bastilles and unknowable poems were expected; instead there are incels and leftbook. (1) Of course, the Internet is also home to social genius and brilliant artworks. But these tend to be exceptions. This is because social media does not help the masses assert their actual subjectivities but leads the masses to create reified performances; it produces subjectivities as simulacra. Just like every other media phase in capital’s history, the majority of the content is mediocre and reinforces bourgeois “common sense.” (2) The difference is that this time we appear to be in control. It is an illusion. We have the apparent form of democratization without social content. We have the unique subject (in theory) without that subject’s emancipation. (3)

Marxism is many things. Whether or not one agrees with the likes of Michael Heinrich that it is not a worldview (I believe it most certainly is), it denotes a varying set of processes of collective and individual human practice and cognition. Whether or not you want to call that a worldview, well, you do you, boo. To define it is thus, in a sense, to engage in it. Marxism of course is not limited to being operationalized, as it were as a “discourse” or a set of written procedures. As is apocryphally told, the great American revolutionary socialist Big Bill Haywood once remarked that he neve read Marx’s Capital but his body was covered with “marks from capital”. Yet accepting the absolute primacy of sensual creative human practice, what Marx calls “form giving fire” of human labour, there is still the word and the set of words, the discourse, better yet, the rhetoric, or even better yet the poetic.

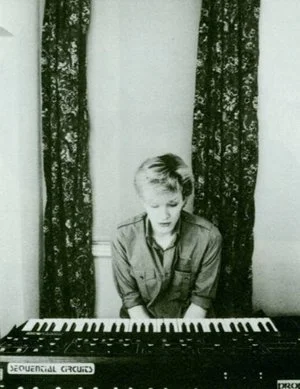

The origins of this piece came out of a discussion about neoliberalism and music in the context of the legacy of the 1960s counter culture. The debate revolved around two lines – whether punk was an ending or continuation of the 60s, and whether neoliberalism has subsumed and commodified counter-cultural themes, making them null and void.

While there have been strides to widen discussions in art history to include issues like gender, sexuality, race, and ethnicity, the corporate marketing of pricey art-history textbooks to American college students produces materials that glaringly omit and/or deemphasize Marxism as an analytical catalyst. In addition, examples of historical experiments with self-described "real-existing socialism" tend to be so grotesquely abbreviated as to distort context and content and preclude understanding.

“Outsider Art” positions art and artists in or outside the art world. “Art Brut” and “Outsider Art” were terms coined during the reign of the modernist avant-garde, in the 1940s and 1970s respectively. In this, whatever problems these concepts had, they initially positioned artists in and outside a conscious stream on ongoing aesthetic innovation, a stream in which a significant minority of artists had political sympathetic with anarchist, socialist, and Marxist politics. But, as Boris Groys observes, the modern avant-garde became, in the late 20th century, a weak avant-garde, avoiding the strong politics of modern art, as well as the strong images of classical and popular culture. There are number of reasons for this transition.

There are concepts whose time has passed, and each usage now betrays or strays from the initial power of the term. “Transgression,” when deployed by such thinkers as Michel Foucault and Georges Bataille in the1930’s-to-late 20th century was a radical concept articulated with change and resistance. That is not to say that transgression wasn’t often a means for the homogeneous order to absorb elements marked outside of it and/or or at its limits.

According to Franco Moretti, the fear of bourgeois society can be summed up in two names: Frankenstein and Dracula. He notes how both were born in 1816 on a rainy evening near Geneva, at a time when industrial development was just beginning to get underway (1997, 83). His argument is that Frankenstein and Dracula are dramatic, totalizing monsters. Unlike the feudal or aristocratic ghosts who were confined to a castle, these figures go international, expressing the motions of capital and labour. While originally published in 1983, his argument resonates most strongly in the late neoliberal period.

Glenn Branca made it to my hometown relatively late in his career; as I recall, he stormed the stage rasping approval after a performance of the first movement of his fourteenth, then most recent, symphony — an overture of ambient menace, moving through the harmonic series in cascading waves. Wild-haired and foul-mouthed, long since an institution, Branca took his time in praise of the neo-romantic program in which he appeared, spitting anachronistic condemnation of musical systematizers such as Arnold Schoenberg and Pierre Boulez. I recall thinking this attempted relitigation of musical modernism extremely telling; no one is a context unto their own, and more often than not an adaptive grudge outlives its object as a useless negativity, festering resentfully.

Marxist cultural criticism, by its nature, walks the tight rope between the Scylla of purely instrumental and didactic analysis and the Charybdis of descriptivism and romanticism. Yet there are times in which Marxist cultural critics must make directly political interventions, emphasizing that indeed we are, in Ash Sarkar’s inimitable phrase, literally communists. This was what gave rise, for example, to Red Wedge statements in support of many of the struggles of the last few years.

The concept of outsider art, or self-taught art, is a lie. It conceals the actual artistic arguments and content articulated by the artists who are described in this way. While the history of the concept is more complicated, its present usage is bound up with a racial, class and geographic othering, which centers the bourgeois and petit-bourgeois institutional art world (located in New York City first and foremost) as the norm (when it is itself the outlier).

Sitting at a piano, decked out in Ray Bans and a black suit, Nicolas Cage sings his heart out about “Pachinko”. A sort of cross between a slot machine and pinball, Pachinko is, like your favorite late seventies rock band, big in Japan, indeed it is part of the fabric of modern Japanese capitalism. Gambling is illegal in Japan, yet Pachinko is tolerated. Instead of winning money at Pachinko parlours, players are awarded golden tickets which are thus exchangeable for cash at other locations affiliated with the parlours themselves. The industry, targeting poor and working-class people not unlike video terminal gambling in North America, is primarily staffed by ex-police.

In August 2018, Labour’s John McDonnell called on Twitter and then in a press release for the relaunch of the Anti-Nazi League. Citing the success of Tommy Robinson and Boris Johnson’s Islamophobic likening of Muslim women to letterboxes, the shadow chancellor said, "Maybe it’s time for an Anti-Nazi League type cultural and political campaign... The ANL pioneered highly influential cultural movements like the Rock Against Racism, which attracted tens of thousands of people of all ages to anti-racist festivals and protests.” The response was predictably partisan: the New Socialist was in favour, Dan Hodges against. Stephen Pollard, editor of the Jewish Chronicle, complained that McDonell was plotting against parliament. ‘McDonnell believes – and says so – that true democracy is on the streets. This seemingly well-meaning tweet needs to be seen in that context. In government, ‘the street’ would be a key weapon in the hard left armoury.’

The internet has caught the Kon-Mari virus. While the book was already a huge best-seller, nothing is really big these days until it hits Netflix, and the TV series of the Mari Kondo getting people to carefully curate their possessions has got everyone talking, and her name has become a verb: kon-mari. Is it reactionary garbage? While Kondo’s brand of de-hoarding is super specific and not even necessarily minimalist, its certainly caught up in the same trends of #minimalism, tiny houses, and getting rid of all your material possessions so you can put them in a backpack, travel the world and work on your laptop trends. Is this stuff actually a bunch of reactionary nonsense? Is it the aesthetic of the condominium industry? Can poor and working class people afford to get rid of their stuff?

We don’t need to listen all that closely to hear the voice of right-wing reaction lately. But over the past few days its questions have been particularly and flagrantly silly. “How dare these brown women swear? How dare they dance? How dare they dress in ways that go against our expectations? And how dare they think they can now walk the halls of Congress? Who do these socialists think they are?”

For sure, all aesthetic standpoints are political, and especially in the United States. This is after all a country where the far-right gained a level of influence it hadn’t seen in sixty years through the election of a reality TV star.

Karl Marx writes in Estranged Labour* that, accepting the presuppositions underlying political economy as it existed at the time of writing, one can see that there is a hell of a lot missing. There is something to it – but it is insufficient. As Marx writes, political economy “expresses in general, abstract formulas the material process through which private property actually passes, and these formulas it then takes for laws. It does not comprehend these laws – i.e., it does not demonstrate how they arise from the very nature of private property.”

One can say the same thing about the dominant form of writing about popular music. It can provide you with consumer knowledge with perhaps a tad more (but only a tad) than an algorithm.

The pooling of artists in global cities has become a destructive anachronism; destructive to artists, working-class communities in those cities, and destructive to art itself.

The formation of art enclaves in industrial capitalism, during a century of accelerating aesthetic and conceptual innovation (1850-1950) had a progressive logic. Artists’ innovations fed off their physical proximity to each other. Moreover, these aesthetic and conceptual interventions were often in political sympathy to the industrial working-class concentrated in cities like London, New York, Paris and Berlin. Artists found a radical, and oftentimes working-class, cosmopolitanism in these artistic enclaves. Gentrification had not yet evolved to exploit artists as it does today.