Classics

The English translation of Richard Wright’s address to the Revolutionary Democratic Assembly in Paris in December 1948 seems to have escaped the notice of the biographers and literary scholars who have otherwise been extremely thorough in documenting the author’s life and work. And that neglect is all the more remarkable given the speech’s substance. A major defense of radical political and cultural principles at a moment when the Cold War was turning downright arctic, it is also a credo, a statement of personal values, by the preeminent African-American literary artist of his era.

To regard the struggle, the pain of a revolution, is not to deny the magnificence and optimism embodied in it. In order to fully look to the future, we have to reckon with the immensity of creating it. And acknowledge that we may fail.

Victor Serge knew this. He supported the Bolshevik Revolution enthusiastically, but as he saw its direction thrown off by civil war and rising bureaucracy, he had little hesitation in dissenting while remaining in absolute solidarity.

Colonial domination, because it is total and tends to over-simplify, very soon manages to disrupt in spectacular fashion the cultural life of a conquered people. This cultural obliteration is made possible by the negation of national reality, by new legal relations introduced by the occupying power, by the banishment of the natives and their customs to outlying districts by colonial society, by expropriation, and by the systematic enslaving of men and women.

Three years ago at our first congress I showed that, in the colonial situation, dynamism is replaced fairly quickly by a substantification of the attitudes of the colonizing power. The area of culture is then marked off by fences and signposts. These are in fact so many defense mechanisms of the most elementary type, comparable for more than one good reason to the simple instinct for preservation.

John Berger is dead. There are very few people who, when they pass on, leave you at such a loss for words. Mostly because there are so few as versatile and prodigious as he was. Art critic, painter, poet, novelist, socialist. And he was consistently brilliant in every one of these roles. Often, he was more than one simultaneously. His first novel A Painter of Our Time was available for a month in 1958 before the publisher withdrew it under pressure from the anti-communist Congress for Cultural Freedom. When he won the Booker Prize in 1972, he donated half the prize money to the Black Panthers. Landscapes, a recently published collection of his works, nestles musings on Cubism next to moving tributes to Rosa Luxemburg.

The Paris Commune was in essence the first large scale experiment in socialist governance. On March 18th of 1871, radical workers and artisans organized in the National Guard decisively took control of the city as the regular French army fled. Days later, the Commune was elected, immediately declaring that workers could take over and run workshops and businesses, as well as abolishing the death penalty and military conscription, mandating the separation of church and state, and the beginnings of a social safety net and pensions. Both revolutionary and democratic, every day saw new ways of running the city advanced by ordinary laborers.

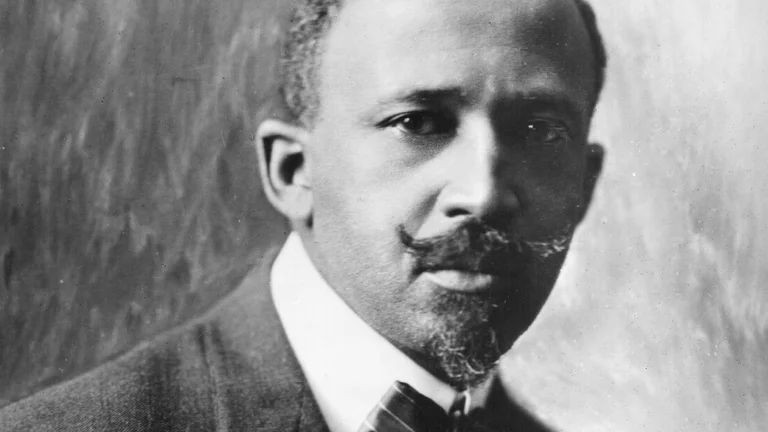

"Black Art Matters." If there were a way to sum up the thrust of this essay in one very brief sentence then that would be it. W.E.B. DuBois is one of those thinkers who needs very little introduction: lifelong socialist and Black liberationist, founder of the N.A.A.C.P., author of what is still to this day one of the definitive books on Black Reconstruction in the south. What is often overlooked is how central art was to DuBois' ideas about Black freedom in the United States.

That DuBois had ideas about art is not very surprising; a writer whose theories were as far-reaching and as all-encompassing as his is bound to encounter the milieu of human creativity at some point. When he claims that "all art is propaganda" he is not claiming that all art should be didactic or stump for a cause, merely that all art, whether honest about it or not, carries with it ideas and social consciousness...

The success of the film Trumbo – starring Bryan Cranston as the titular blacklisted screenwriter and Communist Party member – has come at an interesting time in the American cultural landscape. Discussion of socialism is now commonplace. As is free and open discussion of stripping people of their civil rights because of what their beliefs may or may not be. As a gauge of how important it might be, the film has gladly pissed off the right people.

Filmmaking is a fickle art-form; it is of course impossible to cram every single element of a person’s life into a biopic. Nonetheless, that the film doesn’t mention in any way Dalton Trumbo’s masterpiece novel Johnny Got His Gun is frustrating for those familiar with his work. Telling the story of a young soldier fighting in World War I who, caught in an explosion, loses both arms and both legs as well as his sight, hearing and...

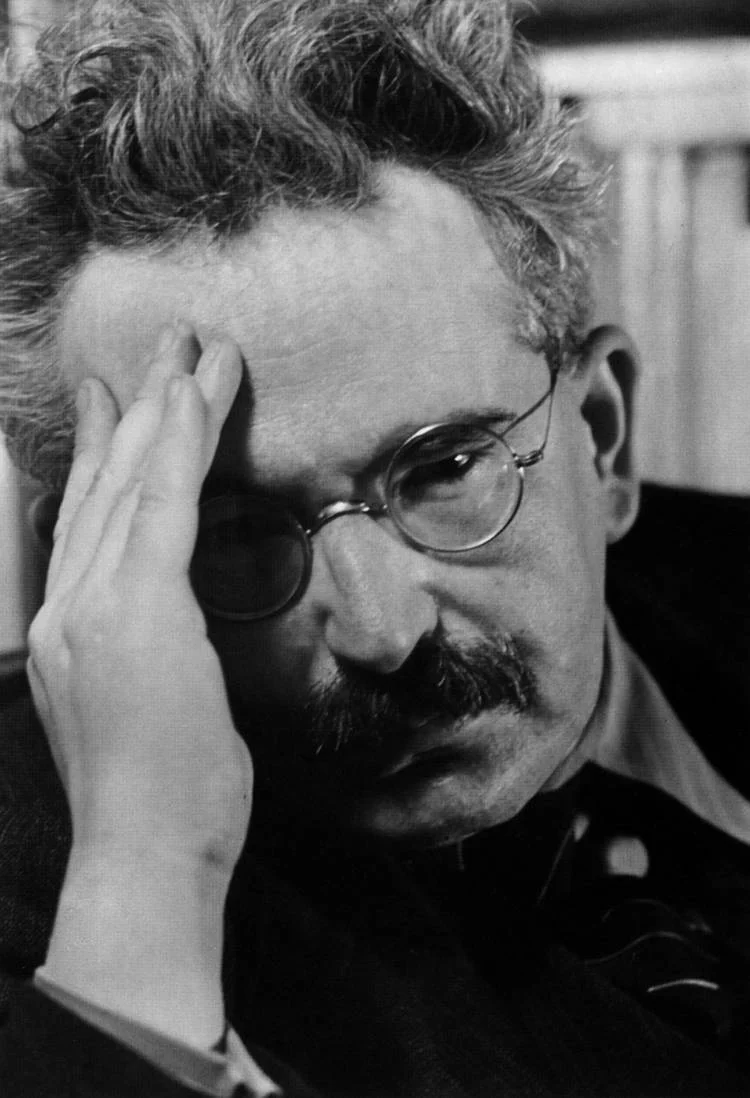

I am told that you raised your hand against yourself

Anticipating the butcher.

After eight years of exile, observing the rise of the enemy

Then at last, brought up against an impassable frontier

You passed, they say, a passable one.

She was one of the many who came to me in those difficult days for advice and spiritual guidance.

I had seen her at a number of delegate conferences, and remembered having been struck by her pretty, rather intense face with its pensive but intelligent eyes.

Today her face was pale, the eyes even larger and sadder than usual.

"I came to you because there is no one else to whom I can go. I have been homeless for the past three weeks – I have no money. I must have work! If I don't get: some means of earning a living soon, there is only one thing left for me – the street."

Sixteen men were executed in the aftermath of the Easter Rising – the seizure of the General Post Office in Dublin by Irish volunteers that took place one hundred years ago this week. Among those executed was James Connolly: leader of the Irish Citizen Army, trade unionist, revolutionary Marxist, de facto commander-in-chief of the Easter Rising.

Connolly has been canonized in the century since his death. That death – at the hands of an occupying British Army – is by itself enough to command respect of anyone concerned with self-determination, but there is also a certain tragedy in how overlooked his eloquent words and ideas can be, even today.