Editors' note: The work of Alexandra Kollontai is essential reading for any socialist or feminist. A member of the Bolsheviks in Russia, she was a key agitator for women's liberation, and founder of the new revolutionary government's women's department: the Zhenotdel. During its short existence, the Zhenotdel waged a heroic struggle throughout the former Russian empire against sexism and misogyny. It represented one of the many radical hopes thrown under the bus of the Stalinist bureaucracy as it rose to power. Though she attempted to resist this degeneration, Kollontai was effectively sidelined politically. She spent the last 25 years of her life as an effective ambassador to other nations (including Mexico and Sweden) but more or less powerless to shape the political direction of the USSR.

This story, written in 1923, reflects Kollontai's often overlooked talent as a fiction writer. "Sisters" is a scathing indictment decline of popular power in Russia and its attendant rise of a new privileged class. It is movingly told through the eyes of revolutionary women, and is a reminder that love — be it "free love" or in its more "traditional" forms — is always shaped by the society in which we live. And that it can rise or fall on waves of revolutionary hope.

* * *

She was one of the many who came to me in those difficult days for advice and spiritual guidance.

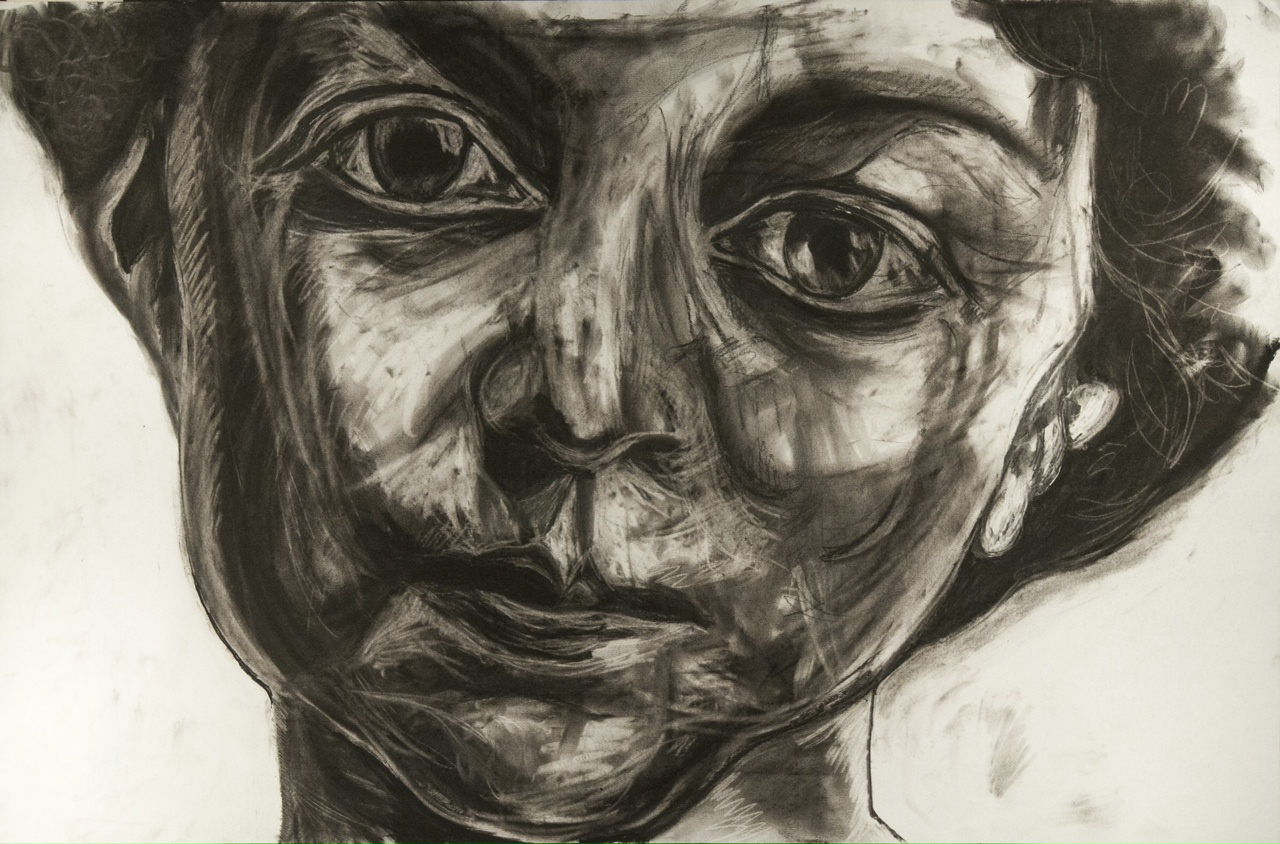

I had seen her at a number of delegate conferences, and remembered having been struck by her pretty, rather intense face with its pensive but intelligent eyes.

To-day her face was pale, the eyes even larger and sadder than usual.

"I came to you because there is no one else to whom I can go. I have been homeless for the past three weeks — I have no money. I must have work! If I don't get some means of earning a living soon, there is only one thing left for me — the street."

"But, let me see. If I remember rightly you were working. You had a good position. Were you discharged?"

"Yes. I worked in the shipping department of our publishing house until two months ago, when I lost my place... because of my baby. It was so sick, and I had to stay at home again and again to take care of it. It died two weeks after I lost my position, but I was not taken back."

I felt that the bowed head and the long lashes were concealing un-shed tears of helpless misery.

"But why were you discharged? Was your work unsatisfactory?"

"No, on the contrary, I am considered an efficient worker. But my husband has a good income — he is an important official in the Combinat..." [1]

"But if that is the case, you are not without means. Have you separated?"

"No, we have not separated... that is, I simply left him, and I cannot go back. No matter what happens to me... I will never go back. Anything but that."

The long lashes no longer hid the tears in her eyes.

"Forgive me! I never cry. I went through this purgatory without tears. But your kindness, your sympathy... make it hard to bear... Let me tell you about it, so that you may understand."

Women of the Putilov Works leading the strike that will kick off the Russian Revolution

She had met her husband at the height of the revolutionary uprising. At that time he was a compositor in the publishing house in whose shipping department she was employed. Both sympathized strongly with the Bolshevist cause, and their burning enthusiasm for the Revolution that was to shake off the yoke of exploitation to build up a new and a more just world, drew them together. They both loved books with the devotion that characterizes those who, self-taught, fight a constant, never-ending battle against their educational limitations. The Revolution, in its dizzy whirl of intense activity, had found work for them both during those mad October days. And in the fire of battle, to the sound of rattling machine guns, their hearts had found each other. There was no time to legalize their union. Each continued to live their own life; they met during hours of work, happy in the glow reflected from stolen hours of passionate companionship. They were legally married a year later, when she became pregnant, and looked forward hopefully to the coming of their little one to the modest home in which they now lived together. But with the birth of the little girl, complications set in. She could not resign herself to the thought of concentrating her entire activity upon her home. Surely work was as important for the woman as for the man, and must not be set aside for family considerations. She urged the creation of a day-nursery for the babies of working women, and was successful in seeing it established. But new difficulties arose almost at once. Her work and the care of the baby, the thousand little ministrations that its comfort at home demanded, left little time for the demands of the household. Her husband grumbled, and while admitting the truth of his remonstrances, she could not quite admit their justification. Was he ever at home? And was he not proud of her when she was elected delegate to the Rayon Congress?

"But won't you be sulky if dinner is cold?" she had teased him when he congratulated her on her success.

"Bah, cold dinner, fiddlesticks! See to it that you do not become cold after meeting so many new and interesting men there. One never can tell, you know. Better be careful."

They had laughed gaily at the thought. Could anything cloud such love as theirs? They were so much more than man and wife — comrades who went through life hand in hand, who aspired to the same ideals, with never a thought of themselves. Only their work, that, and each other. And the baby, of course, the dear, joyous, healthy girl baby!

How was it possible that all this had changed so? Perhaps the Combinat? Sometimes she thought... They had rejoiced at his appointment, of course. It meant a little ease and comfort after the hard life they had been leading; no more starvation, no more worn-out, ugly clothes, no anxiety lest lack of funds close the nursery and leave her with the problem of conflicting work and family responsibilities. When the new appointment came, her husband had urged her to give up her job. It irked his pride that she should continue to work for wages, now that he was able to support his family. But she resented the very suggestion. She was accustomed to the daily intercourse with her fellow workers, and enjoyed the responsibilities of her daily task. Besides, she hated the thought of dependence, she who had taken care of herself since the days of her earliest youth. Still, things were easier. They moved into more comfortable quarters — two rooms and a kitchen — and engaged a girl to take care of the baby, while she devoted herself more intensely than ever to her work in the Rayon. Her husband was busy, too. He spent only his sleeping hours at home.

Thus they lived busy but happy days until her husband was sent away to accompany several Nepmen on a business trip. [2] A stranger returned to her, one who wore fine clothes and used perfume, who barely listened when she spoke of the things that had formerly interested both of them. He began to drink, he who had never, with the possible exception of an occasional holiday, used liquor before. During the Revolution there had been no time for alcohol.

The first time he came home under the influence of liquor she was frightened rather than grieved. "It will hurt him," she thought, anxiously. "His reputation will suffer." But when she reproached him the following morning he drank his tea morosely and refused to answer. Three days later he was drunk again, this time so helplessly that she could scarcely get him into bed. It was disgusting. Even when one loved a man with all one's heart, it was disgusting. Then she approached the subject again. The following day he looked at her with eyes so full of hatred and resentment that the words she would have spoken stuck in her throat.

After that he came home drunken more and more frequently. It was intolerable. She used to linger at home in the morning until he became sober, to urge him to mend his ways, to show him that this could not go on. She showed him what he had made of their marriage — comrades no longer, now, but a man and a woman, whom only the common marriage bed held together. She warned him, she called him to shame, she wept...

At first he listened, tried to defend himself. She did not understand. He must go about with these Nepmen. If one did not take part in their amusements, one could not do business with them. Occasionally he would become thoughtful, would admit that he himself was becoming tired of the life his position was forcing him to lead. Those were the times when he would plead with her to be patient, taking her head between his hands and looking deeply into her eyes, sending her lightheartedly to her work once more.

A cartoon rendering of a Nepman, from Dziga Vertov's Soviet Toys

A week later he was hopelessly drunken again. He pounded the table with his fists when she spoke to him. "Mind your business. They all live like this. Go away, if you don't like it. No one is holding you here!"

She went through the day after that scene with an intolerable hurt in her breast. Was it possible that he no longer cared for her? Did he want her to leave him? But he was deeply contrite that evening, and apologized abjectly for the things he had said. They talked it all over again and again, and her heart felt light, confident once more.

She understood, of course. It was this company he was forced to keep. He earned his money easily, and had to spend as the others did. Men were like that. They could not refuse to join the rest. He told her stories of the lives these Nepmen led, they and their wives, of how they did business, and how hard it was for a worker to beat these sharks at their own game.

It all made her very unhappy. She was more dejected than she had been since the days before the Revolution had put an end to the misery of the war. The glory of the Revolution was giving way to bitter realities — these Nepmen, and the threatening reduction of workers due to the new policy of expense retrenchment.

For it was at this time that she first heard that she would probably be affected by the coming layoff. Her husband took the news of her coming discharge with maddening calmness. "On the whole," he thought, "not a bad thing for both of us. You would be at home to attend to the household as it should be looked after. Look at it now — impossible to invite respectable people to visit in a place like this."

When she remonstrated indignantly with him he grew impatient.

"All right, all right. After all, it's your business, I suppose. I'm not hindering you. Keep on working, if you choose."

It hurt her deeply to think that her husband was offended; hurt still more to think that he did not understand her. She persisted nevertheless. She went to influential comrades, argued with them, almost quarreled with them at their refusal to understand that her husband's income had nothing to do with her right to work, and in the end actually persuaded them to reconsider her dismissal. But she had scarcely adjusted matters when her little one became seriously ill.

"You cannot imagine the wretchedness of those nights, sitting alone with my unhappy thoughts beside the baby's bed. I was so desperately lonely, so anxious for the future! One night the door-bell rang. I ran as usual to open the door for my husband, glad to have him with me. Someone to whom I could speak of my fears, someone who loved the little one. If only he was not drunken... When I opened the door I could hardly believe my eyes. A young woman stood beside him, rouged and drunken, an unmistakable type. 'Let us in, wife,' he said, grandly, with a drunkard's swagger. 'This is a little friend I brought with me tonight. I want to enjoy life like the rest of them enjoy life, I say....Leave us alone.'

"My knees shook. They went together, laughing inanely, into the living-room where my husband usually slept. I hurried back to the baby, who began to whimper at the noise, and locked the door behind me. I calmed the little one, and then sat there beside her bed, staring before me as my world crumbled into ashes. I was not angry at him. What can one expect of a drunken man? But it was horrible. One could hear every sound in the next room. I longed to hold my hands over my ears, but the little one needed constant attention. Fortunately they soon quieted down — they were too drunken to stay awake. Toward morning I heard my husband open the door for the woman. He himself went back to sleep.

"He slipped out of the house that morning without seeing me. When he returned in the evening I did not look up. He buried himself in his papers, but I caught occasional stealthy glances in my direction. 'He will probably beg to be forgiven, only to go back to his old ways again.' But I was through. I was determined to leave him. Yet my heart ached at the thought. I still loved him... Why deny it? I love him even now, when it is all over. But it is as if he were dead. Now I could not go back to him again. But at that time my feelings for him were still alive.

"Dully I remembered a Rayon meeting I had promised to attend and slipped into my coat. But before I reached the door he had jumped up from his chair, and bore down on me with an incredible rage. There were blue spots on my arm afterward, where he had held me as he'd pulled off my coat and flung it to the floor.

"'I'm thoroughly tired of your hysterics,' he shouted. 'Where are you going? What do you want of me? You will have to go far to find another husband like me, able to take care of you and give you a decent home and respectable clothes. I fulfill your every wish. What right have you to sit in judgment over me?'

"He talked and talked — endlessly. He raged, he explained, he tried to justify himself. And because I saw that his face was distorted, because I saw that he was suffering, I was so sorry for him that I forgot everything else. I still loved him so very much, you see. Perhaps if I encouraged him, showed him that things were not as bad as they looked, that he was not to blame, that these Nepmen...

"So we were reconciled to each other once more. But I had to promise never to be angry with him again. Of course he would never have brought home this woman if he had not been drunk. I pleaded with him to stop drinking. Everything would be different — I hadn't minded the prostitute nearly as much, I assured him, as the bestiality of it all. He promised to control himself. He would in the future avoid these men who were leading him to destruction.

"But, of course, the thorn remained. Could he have done a thing like that, I asked myself over and over again, if he still loved me? Would he have visited a woman like that during those days in the Revolution when we were so happy together? One of my friends, far prettier and younger than I, had set her cap for him when we first met each other. But he had not even noticed her. I tried to speak of this to him. He must tell me, if he no longer cared for me. I would not stand in his way. But he became angry at once, and thundered at me that I was driving him out of the house with this silly woman's talk. Devil take me and all women! Just when he was so busy, too, that he didn't know his head from his heels for business worries!

"So matters drifted along. Meanwhile my discharge became more and more imminent. My little daughter was still sick, and it was too much to expect them to hold a position for me that I was, for the time being, so obviously incapable of filling. I remained at home, and tried to make the home more comfortable for my husband. I still hoped that things might change for the better, meanwhile trying everything possible to hold my position. The thought of absolute financial dependence on my husband at this time threw me into blank despair. We occupied the same rooms, but lived as strangers. We saw very little of each other. He had even lost interest in the little one. He hardly looked at her. He drank less, it is true, and came home sober most of the time. But it was as if I had ceased to exist. He slept on the divan in the living-room, while I stayed in the bedroom beside my little girl. Occasionally he came in to me at night. But there was no joy in his embraces. The days that followed them were, if possible, more dreary — as if new suffering had been added to the old. He took me as a matter of course, and apparently never thought of the things that must be going on in my mind...Thus we lived... Lonely. Silent.

"Just before the baby died, I was definitely discharged. There was a dim ray of hope in my anguish when she left us. 'We will suffer together, now, we two,' I thought. 'It will bring him back to me.' But I was mistaken. He did not even attend the funeral — an important meeting. I was left alone with my sorrow — without work, dependent for support on a man who no longer cared for me.

"Liberated Woman, Build Socialism," 1926

"There was work enough to be done in the Rayon. But it was voluntary work, party propaganda, educational work, organization tasks. This sort of work was not paid, of course. Nor could I ask for a position when so many were out of work. Was not my husband a well-paid official? I tried and tried, but there was nothing to be had. I tried to be patient. I still hoped. Something might happen. We women are so foolish. It was so obvious that my husband no longer cared for me. And within me, too, bitterness and resentment were slowly killing the love that remained. Still I waited. Each morning I woke up, hoping against hope for a miracle. At night I hurried home from the Rayon like a child — perhaps he is at home, waiting for you! Perhaps... But even when he was at home, it made no difference in my loneliness. He paid no attention to me, he was busy with his work. Comrades came, Nepmen. Still I hoped and waited. Until that happened which made me leave him. Definitely, this time. Never to return to him again.

"I had returned late from a meeting that night and was just lighting the samovar for a cup of tea when I heard the outer door open softly. Since that episode my husband carried his own key. He went directly to his room, as usual. After a few moments I recalled a package that had come to him by special messenger that afternoon. I went to my room to get it, and took it in to him. What I saw there — it was even harder to grasp than the first time. For he was not drunk. There beside my husband stood a tall, slender woman. They both turned to look at me, and our eyes met.

"I can just dimly recollect what happened after that. I believe I managed to tell him calmly as I laid it on the table, that the package had come for him by special messenger. Then I went to my room. But when I was alone once more my limbs shook so that I could hardly control them. Fearful of betraying myself to those two in the next room I crept into bed and drew the covers over my head. I wouldn't hear, wouldn't feel! But who can escape the torture of his thoughts?

"I heard their voices, hers louder than his, as if she were upbraiding him. 'Perhaps he is her lover, and she has just discovered that he is married. At this moment he may be denying that I am his wife!' I thought of every possibility, and each thought brought untold misery. I had suffered less, bitterly as I was hurt, when he brought the prostitute into our home. He had done that after a drunken spree. But this... Now I knew that he no longer cared for me. Not even as one cares for a comrade or a sister. He would not have brought a woman into the home in which his sister lived. He would have shown her more respect than to bring such women — women of the streets into the rooms she occupied. This, too, must be one of them. No decent woman would have come with him at this hour of the night! A flood of rage at this woman took possession of me. I could have rushed into the room in which she lay with my husband and driven her out of the house.

"Thus I lay, sleepless, until the dawn broke. Then it seemed to me that I heard stealthy footsteps on the corridor. It must be she! The kitchen-door opened softly. What did she want there, I asked myself indignantly? I waited tensely. She did not return. With sudden resolution I jumped out of my bed and went into the kitchen. She was sitting on the little bench by the window, her head bowed down, crying bitterly. Her fair hair was so long it almost covered her slim body. When she looked up at me as I opened the kitchen door, I was dismayed at the suffering in her eyes. I approached and she rose to meet me.

"'Forgive me,' she whispered, 'for having come into your home. I did not know, of course. I thought he lived alone. That makes it so hard, so very much harder to bear.' At first I did not understand. 'This is no prostitute,' I thought. 'She is his friend.' And the words 'Do you love him?' came impulsively to my lips.

"She looked at me with large, astonished eyes. 'I never saw him before. We met last night for the first time. He promised to pay me well. It does not matter to me who the man is, so long as he pays.'

"How it all happened I can't remember. She told me her story — how she had been discharged three months before when the reduction of labor was put into effect, how unhappy she had been not to be able to help her old mother who wrote that she was starving, how she had finally gone on the street, and had been fortunate in making the acquaintance of an agreeable circle of men almost at once. Now she was well dressed and well fed, and able to take care of her mother... She wrung her hands as she told me her story.

"'I might be a useful worker,' she assured me. 'It is not that I am ignorant. I have my gymnasium diploma, and I am young — only nineteen. To think that I must go to the dogs like this.'

"It is hard to believe, is it not, that I trembled with sympathy for this unfortunate creature. For it struck me, as she was telling her story, that only my husband's income had saved me, up to this time, from a similar situation. The hatred that I had felt for her that night as I lay on my pillow was turned against my husband now. How dared he exploit the misfortune of a poor woman, a working man proud of his understanding of the problems of his class, a man who boasted of his responsibility to the proletariat! He who should have helped an unemployed comrade in her hour of need buys her body... It was so utterly revolting that my mind was made up as she spoke. I could not live with a creature of that sort a moment longer.

"We discussed the whole question while we lit the fire and cooked our coffee together. My husband was still fast asleep. When she prepared to take her leave I asked her,'Did he pay you?'

"She blushed furiously and assured me that to take money after she had spoken to me was out of the question. I understood her anxiety to be out of the house before my husband should find her with me, and I did not detain her. Will you understand me when I tell you that I hated to have her go? It was as if she were some dear relative....she seemed so unhappy, so young and so alone in the world. I finally dressed and went with her. We walked through the streets for a long time and finally sat down together on a bench in a small park. I told her of my unhappiness. I still had most of my last salary left and persuaded her to accept it from me. At first she refused, but she took it finally on condition that I come to her in case of need. We parted like sisters.

"That night my love for my husband died, died suddenly as if it had never been. There was no pain, no feeling of offense. It was as if I had buried him. When I returned home he was still there, vociferous in self-justification. But I did not answer. There were no tears, no recriminations. On the following day I moved my few belongings to the home of a friend and began to look for work. That was three weeks ago. The outlook has been hopeless. Then, several days ago, something occurred that made it clear to me that I could stay with my friend no longer. I went to look for the girl my husband had brought with him that night, and was told that she had been taken to the hospital on the day before... So I am drifting about without a home, without work, without money. Will her fate be mine?"

The tragic, despairing eyes of my visitor asked this question of life. It was in her eyes – the sorrow, the horror, the misery of this struggle against the workingman's most implacable enemy — unemployment. The eyes of a defenseless woman who, alone and single-handed, is fighting the old, worn out order.

She has gone, but her eyes still haunt me. They demand an answer. Action, constructive action. Struggle.

Footnotes

- "Combinat" is Russian for "combine," in this context meaning an amalgamation of manufacturing enterprises in related industries.

- The "Nepmen" were the nickname for those who were allowed to run private, for-profit enterprises during the New Economic Policy ("Nep" being an abbreviation of that same policy). The New Economic Policy was instituted as a means of addressing the economic devastation that came as a result of the Russian Civil War where fourteen foreign armies attempted to crush the revolution. Though discontinued after Stalin's rise to power, the policy nonetheless aided in the rise of a new privileged class in Soviet Russia.

The English translation of this story was done by Lily Lore, and appeared in the 1929 story collection A Great Love. It is also available at the Marxists' Internet Archive.

Red Wedge relies on you! If you liked this piece then please consider donating to our annual fund drive!

Alexandra Kollontai was a Russian communist revolutionary and campaigner for women's liberation. After the Russian Revolution she founded the Zhenotdel, or "Women's Department."