Introduction

What is the relationship between artistic movements and the historical periods during which they first appeared? Can the methods associated with these movements be detached from their original context for the benefit of later artists? Do the answers to these questions depend on which movements and periods we are discussing? The issue is of more than academic interest. Serious contemporary artists want to produce work relevant to, and critical of the societies in which they live; but in doing so, are they free to draw on any methods, from any point in history, or will only some be adequate to their needs? Should socialists expect them only to work with particular methods, and criticise them when they do not? The tensions involved are suggested by Yates McKee in his important recent work, Strike Art, which he begins by affirming intention to produce “a strategic address to those working in the art field… to consider how the various kinds of resources at our disposal might be channeled into movement work as it unfurls with ongoing moments of political rupture”. At the conclusion, however, he also reminds us that: “Art is not just an instrumental channel for this or that end. It is a sensuous imaginary in which forms of life emerge, break down, and recombine.”[1]

These are scarcely new considerations. For most of the twentieth century, the debate among Marxists over these and similar questions centered on the respective merits of realism and modernism, most notably during the 1930s in the exchanges between Georg Lukács, Bertolt Brecht, and various members of the Frankfurt School. Before going on, however, it is necessary to make an important distinction. There are, in the cases of both realism and modernism, theories which seek to explain how these movements were produced by certain historical developments, how they consisted of certain artistic practices and embodied certain cultural meanings. Since the 1930s and 1940s respectively, the dominant theories of realism and modernism have, however, also functioned as ideologies, representing in cultural theory the defence of existing class societies, a task which involves, among other things, prescribing what art can and cannot do. This ideological role does not invalidate every aspect of these theories, it simply means that Marxists can neither adopt them directly nor adopt them indirectly while inverting their value judgements. They themselves must first be subjected to critical analysis. In short, neither realism nor modernism is necessarily what the ideologists of realism and modernism say they are.

Until relatively recently, the orthodoxy was that since the late 1970s, realism and modernism have been joined by a third movement called “postmodernism”, expressive of our own “late” capitalist era, which had supposedly superseded them both.[2] If, however, we set postmodernism to one side for the moment, the question still remains of the extent to which realism and modernism themselves corresponded to particular stages in the development of capitalism (if indeed they do), and what this means for our attitude towards them. I want to approach the issue by way of a critique of the greatest twentieth–century defenders of realism and modernism; the Hungarian literary critic, Georg Lukács (1885 – 1971), in the case of the former and the US art critic, Clement Greenberg (1909 – 1994), in that of the latter.

Apart from those who attended art school in the 1960s and early 1970s, it is unlikely that more than a handful of the Marxists familiar with Lukács have a similar knowledge of Greenberg, yet for years he held a position of critical authority in the visual arts of comparable stature to that of Lukács in literature. Indeed, he is the only figure who even approximates to Lukács on the Western side of the Cold War divide. Neither man seems to have referred to the other, let alone engaged with his work.[3] Nevertheless, the parallels in their lives are remarkable: the same initial revolutionary commitment (the Third International and the Communist Party of Hungary after the Russian Revolution in the case of Lukács, a more amorphous Trotskyist milieu after the rise of Stalinism and Fascism in the case of Greenberg); the same capitulation to the local centre of imperial power (the USSR, the USA); the same elevation of one artistic movement (realism, modernism); the same privileging of one discipline within that movement (the novel, painting) and of one style within that discipline (Critical Realism, Abstract Expressionism). Greenberg’s career did, however, differ from that of Lukács in four important ways and, given the criticisms which I make of Lukács in what follows, it is important to stress that these differences all reflect rather better on him than they do on Greenberg.

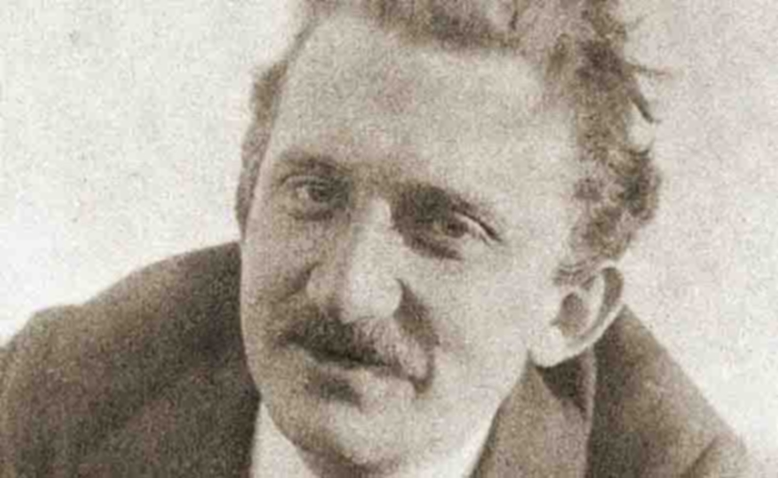

Georg Lukács

First, Lukács was among the leadership of the Communist Party of Hungary from its formation in 1918, and remained a member even after being politically silenced in 1929. Greenberg was never a political activist and, indeed, does not appear to have been a member of any organisation during his Marxist period, although his known associations and few directly political writings suggest that he was close to the Worker’s Party led by Max Shachtman.[4] He was instead a proponent of what John Newsinger calls “literary Trotskyism”, the main vehicle for which was the New York journal Partisan Review. Greenberg joined the editorial board in early 1940 and remained a member until late in 1942 when he was drafted.

Second, Lukács was a key participant in several important debates within classical Marxism (the changing nature of class consciousness under different modes of production, the type of political organisation appropriate to the age of imperialism, etc.). Indeed, along with Gramsci, he was one of the few Marxists outside Russia who tried to integrate and develop Leninist positions, often as a creative response to his own errors, such as support for the ultra–left March Action in Germany during 1921. Greenberg was never involved in these central political debates, the overwhelming body of his Marxist work being devoted to cultural issues. Moreover, those writings which do touch on contemporary politics reveal an overall understanding of Marxism which is at best superficial. He took a revolutionary defeatist position prior to the US entering the Second World War, arguing that only a socialist Britain or USA would be able to defeat Hitler – indeed, that without the victory of socialism these states would themselves become fascist, either through imitation of the Axis powers or conquest by them – but nowhere explains how the victory of socialism will be accomplished.[6] And although his opposition to Stalinism certainly draws on Trotsky’s analysis, Greenberg was generally happier counterposing Rosa Luxemburg to both Lenin and Trotsky, on the grounds that her views on organisation are more appropriate than theirs to Western conditions. He did not believe that Lenin led directly to Stalin, but does appear to have believed that the organisational forms imposed by Stalin on the Communist parties were genuinely Leninist, and that, indeed, they were what Stalin could legitimately claim to have inherited from Lenin.[7]

Third, Lukács, even following his capitulation to Stalin after 1929, never made denunciations to the authorities, in either Russia or Hungary, although he was himself in danger on several occasions, being arrested in Russia at the beginning of the 1940s and coming under attack for his alleged deviations in Hungary at the end of that decade. His denunciations were reserved for the Modernist writers, very few of whom – if by lucky chance they were still alive – were still writing in Stalinist Russia. As Marshal Berman comments: “The one great modernist within his reach, whom he violated and brutalised shamefully, was himself”.[8] Greenberg, following his capitulation to US imperialism after the Second World War, was involved in “naming names” during the McCarthyite persecutions. In particular, he denounced editors of The Nation – a journal on which he had once worked – to the American Committee for Cultural Freedom (ACCF) in 1951, after which his accusations were approvingly read into the Congressional Record. When another ex–Trotskyist, James T Farrell, moved a motion which would have committed the ACCF to a position that McCarthyism was the greatest danger to freedom in the USA, Greenberg was among the majority who voted it down.[9]

Fourth, and finally, Lukács was never entirely accepted by the Stalinist cultural apparatus, at least while Stalin himself was alive. His views were too subtle, his internationalism too inflexible, to be wholly suitable for the purposes of the dictatorship. About its preferred spokesman, Stalin’s cultural commissar Andrei Zhdanov there were no such problems. As Susan Sontag pointed out while Lukács was still alive, only his first two (pre–Marxist) books were written in his native Hungarian; the rest were written in German: “By concentrating on 19th century literature and stubbornly retaining German as the language in which he writes, Lukács has continued to propose, as a Communist, European and humanist – as opposed to nationalist and doctrinaire – values; living as he does in a Communist and provincial country, he has remained a genuinely European intellectual figure.”[10] Given the official anti–German xenophobia generated by the regime after the launch of Operation Barbarossa, and which continued into the 1950s, this was a more principled position than the liberal internationalist one that Sontag applauds. Greenberg was personally the leading spokesperson for the dominant interpretation of the visual arts in the West – or at least the English–speaking West – and was honored accordingly. During the 1960s he was sponsored by the US State Department to appear in countries from Japan to Ireland as representative of the ideology of Modernism in art and, indirectly, to demonstrate the supposed individualism and freedom of expression encouraged by the Free World against the actual political conformity of the Socialist Realism imposed behind the Iron Curtain.[11]

Clement Greenberg.

I am not therefore suggesting that there is a moral or political equivalence between the two men. But despite his political trajectory, it is worth considering Greenberg in the same context as a figure like Lukács, who is universally acknowledged as an important Marxist thinker. Both men produced theoretical work during their revolutionary years which can help us undertake a critique of the ideologies they later came to represent. In the case of Lukács, whose major considerations on culture and art were produced either before he became a Marxist or after his capitulation to Stalinism, it has to be extracted from the discussions of totality in History and Class Consciousness.[12] In the case of Greenberg, however, it can be found in writings which directly engage with the position of art and culture under capitalism, and that alone must give him a claim on our attention.[13] Both offer insights which – if subjected to critique from a position external to their own theoretical assumptions – might be incorporated into a more satisfactory Marxist explanation of the relationship between particular artistic forms and different stages in the development of capitalism. From what position should such a critique be launched?

The spectre of Leon Trotsky is mentioned alongside Lukács and Greenberg in the title of this article, and while Trotsky had a perfectly coherent theory of art in general (set out most fully in Literature and Revolution), he neither distinguished between realism and modernism, nor explored their respective relationships to capitalist society – no doubt as a result of having rather more urgent problems to deal with. Nevertheless, his ghostly presence is invoked here for two reasons. First, although Trotsky and Lukács never directly engaged with each other’s positions, the former’s work stands as a silent rejoinder to that of the latter, at least as relevant as the actual debates between Lukács and Bloch, Adorno or Brecht. Second, Trotsky’s position was developed by some of his American followers, although their achievements have largely been ignored by later Trotskyists. It is one of the ironies of the Cold War that one of them was – the young Clement Greenberg! But the positions taken by Greenberg after the Second World War no more invalidate his earlier work than the positions taken by Lukács after 1929 invalidate History And Class Consciousness, Lenin, or “Tailism and the Dialectic”.[14]

Critical Realism and the Popular Front

The writings of Georg Lukács span a period from before the First World War until the revolutionary upheavals of 1968 and after. The majority of this vast body of work is concerned with aesthetics and, more specifically, with literature; the main exceptions being the products of his revolutionary period between 1919 and 1929 when he was far more involved with directly political questions. The argument contained within the main body of his later work is presented differently over time, depending on the vagaries of the political situation – most obviously on whether particular works were written before and after the death of Stalin in 1953 – but what is remarkable is its overall consistency.

For Lukács, realism in general had been, from Shakespeare and Cervantes on, the literary tendency most expressive of the bourgeois world view during its prolonged struggle against the feudal nobility and the absolutist state. The realist novel in particular was the form which played that role at the climax between the opening of the French Revolution in 1789 and the failure of the revolutions of 1848–9. For it was during this period that the bourgeoisie advanced from control of the geographical peripheries of the system – the United Netherlands, England and the Scottish Lowlands – and established themselves (at least in the economic sense) as the ruling class throughout Western Europe and North America. The French Revolution in particular saw the involvement, for the first time, of the mass of the population as a historical factor; first in the French crowds who ensured its victory, and then in the mass conscript armies – on both sides – which fought the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars across Europe: “Hence the concrete possibilities for men to comprehend their own existence as something historically conditioned, for them to see in history something which deeply affects their daily lives and immediately concerns them.”[15]

It was this new historical consciousness which informs the novels of Walter Scott (1771 – 1832) in Britain, James Fenimore Cooper (1789 – 1851) in North America and Honore de Balzac (1799 – 1850) in France. It did not mean, however, that their work was only concerned with great historical events. According to Lukács, “The central aesthetic problem in realism is the adequate presentation of the complete human personality.”[16] This problem could not, however, be resolved by focusing on men and women solely as individuals: “For the inner life of man, its essential traits and essential conflicts, can be truly portrayed only in organic connection with social and historical factors.”[17] The presentation of these factors must in turn conform to certain aesthetic laws: “The true artistic totality of a literary work depends on the completeness of the picture it presents of the essential social factors that determine the world depicted.”[18] The key concept here is that of totality: the means by which the author penetrates the superficial appearance of events as registered by the individual characters, and displays instead the interconnections between them and the society in which they live. By following this method, the great realists could portray aspects of social reality which their own convictions might otherwise have led them to pass over: “We are concerned here, of course, with the intention realised in the work; it need not coincide with the writer's conscious intention.”[19] Thus, whatever feelings of Scott for the Highland clans, of Fenimore Cooper for the Native Americans, or of Balzac for the French aristocracy, all were driven in their art to show these groups as obstacles to the development of capitalism, and whose ultimate fate was sealed by that development.

Lukács held consistently to the position that the connection between class position and aesthetic form remains even after the revolutionary phase of bourgeois history is over, but to different effect, for the art of the subsequent period is therefore the obverse of that produced earlier. Lukács is absolutely explicit about the date after which this reversal takes place, writing that “the decline of bourgeois ideology set in with the end of the 1848 revolution”.[20] From around that date – and certainly no later than 1871, the year of the Paris Commune – the bourgeoisie are said to have abandoned the struggle to reconstruct society in its own image, and settled instead for an alliance with their former aristocratic enemies against a now infinitely more threatening proletariat. In other words, the bourgeoisie had gone from a class challenging for power and anxious to reveal the workings of the society they were in the process of conquering, to one in control, all too aware of the class threatening their position, and as anxious to conceal the reality of this new situation as they had been to confront the old.

The realist novel therefore enters a decline after 1848: “The evolution of bourgeois society after 1848 destroyed the subjective conditions which made a great realism possible.” In the first place, these changes affected the novelists themselves: “The old writers were participants in the social struggle and their activities as writers were either part of this struggle or a reflection, an ideological and literary solution, of the great problems of the time.”[21] Dissatisfied with the world which the bourgeoisie had made, but unable to embrace the alternative, the novelists first retreated to reporting the surface of events, to mere naturalism: “As writers grew more and more unable to participate in the life of capitalism as their sort of life, they grew less and less capable of producing real plots and action.”[22] Then, in a further declension, came the retreat inwards signalled by the rise of modernism. “Modernist literature thus replaces concrete typicality with abstract particularity.”[23] Lukács does allow, however, that this shift did not take place uniformly. In societies which had neither experienced the bourgeois revolution nor completed the transition to capitalism, the conditions still obtained for great realist writing to take place. In particular he refers to the work of Henrik Ibsen (1828 – 1906) in Norway and, in particular, Leo Tolstoy (1828 – 1910) in Russia, but this could only be a temporary salvation for the form.[24] Lukács thus accounts for some late exceptions in a manner compatible with his general thesis. In the case of others which are clearly associated with the triumphant bourgeois world, however, he simply – and not very convincingly – cites uneven development without any attempt at explanation: “Of course we can find many latecomers–especially in literature and art – for whose work this thesis by no means holds good (we need only mention Dickens and Keller, Courbet and Daumier).”[25]

Largely consistent up till this point as a purely historical argument, Lukács now shifts ground and asserts that, far from being tied to a class which no longer has need of it, realism has the potential instead to become a method appropriate to the cultural politics of the working class. Thus, in one of his contributions to the debates of the 1930s, he writes that:

Through the mediation of realist literature the soul of the masses is made receptive for an understanding of the great progressive and democratic epochs of human history. This will prepare it for the new type of revolutionary democracy that is represented by the Popular Front... Whereas in the case of the major realists, easier access produces a richly complex yield in human terms, the broad mass of the people can learn nothing from avant-garde literature. Precisely because the latter is devoid of reality and life, it foists on to its readers a narrow and subjectivist attitude to life (analogous to a sectarian point of view in political terms).[26]

We will learn in due course what Lukács means by “the sectarian point of view in political terms”; for the moment it is enough to note that his conception of the political uses of realism remained constant thereafter. Even after the death of Stalin he continued to argue for the same position:

...socialism is the most effective way of fighting the forces the bourgeois writer has always fought. [i.e. “German Chauvinism, Imperialism, Fascism, and the ideology of the Cold War” – ND] The fight against the common enemy, which has led to close political alliances in our age, enables the critical realist to allow for the socialist perspective of history without relinquishing his own ideological position.[27]

This contradiction has haunted socialists who attempt to use Lukácsian categories. Is it a method destined to decline with the revolutionary potential of the bourgeoisie which gave it birth, or one which, detached from its origins, still represents a resource for critical artists today? And the contradictions do not stop there. “Lukács asserts that realistic literature has been produced by both bourgeois and socialist writers”, notes George Parkinson:

That he should assert this of socialist writers is not surprising, but may seem strange that he should grant the existence of bourgeois realists. We have seen that realism implies a grasp of reality; but in History and Class Consciousness… Lukács argues that the bourgeoisie, by virtue of its very nature as a class, is incapable of grasping a totality, which is something that only the proletariat can achieve.

Does Lukács, as this would suggest, therefore expect realist literature to be produced, if not by proletarians, then by writers who adopt “the perspective of the proletariat”, those whose sense of totality is informed by Marxist theory? No. “Lukács’ explanation of the existence of bourgeois realism is that some bourgeois writers were capable of grasping a totality after a fashion, though their knowledge of this totality was class–limited and their dialectics were only instinctive.”[28] In fact, the later Lukács goes out of his way to argue that realism can be produced by writers who are neither Marxists nor even socialists. These contradictions flow from the political tradition within which Lukács stood during the period when his major works of criticism were written: Stalinism.

Trotsky versus Lukács

It is true, as Alex Callinicos writes, that “the validity of an argument, or the cogency of an analysis” can be “at least partially independent of the perspective from which it comes”.[29] Marxists have, however, rightly taken a sceptical – indeed, incredulous – view of the claim that analysis can be entirely divorced from perspective. Lukács did not, as is often stated, make “concessions” to Stalinism, as if Stalinism was something external to him. He was a Stalinist. Not because he necessarily supported policies of (for example) starving Ukrainian peasants, super-exploiting Russian workers or murdering Bolshevik cadres, but because he supported the policies of Socialism In One Country, and of the Popular Front and its later variations (“anti-Monopoly Alliances”, etc.). This is not meant dismissively. The majority of the best militants and intellectuals in the working class movement made exactly the same choice for exactly the same reasons – a darkening world situation in which the very defeats brought about by Stalinism bound the most advanced sections of the working class ever more tightly to the Russian regime – but it did have considerable implications for his theoretical work. In particular, these works, whatever merits they otherwise possess, were an intellectual defence of the Stalinist politics in the field of culture. As Michael Lowy writes: “Disorientated by the disappearance of the revolutionary upsurge, Lukács clung to the only two pieces of ‘solid’ evidence which seemed to him to remain: the USSR and traditional culture."[30] And from 1928 onwards, he was engaged in a consistent project to reconcile them.

The period between 1928 and 1935 saw the consolidation of the Stalinist regime within the USSR and the imposition of the “Class against Class” line on the Communist International without. The sectarian dementia which accompanied both was unpropitious for such a project, but the adoption of the Popular Front after 1934 gave Lukács his opportunity. As Isaac Deutscher wrote of his work from then on: “He elevated the Popular Front from the level of tactics to that of ideology: he projected its principles into philosophy, literary history and aesthetic criticism.”[31] The Congress of Soviet Writers in 1934 was the turning point. Here the doctrine of “Socialist Realism” was proclaimed and modernism attacked, particularly as manifested in the work of James Joyce.[32] Ben Watson notes of the positions endorsed at the Congress that: “Literature is treated like arms production: fascism could only be defeated by adopting its capitalist methods.”[33] (It is worth noting, in this connection, that it was not only in Stalinist Russia, but in Fascist Germany that “a restoration of former bourgeois cultural forms and relations is instituted” during the 1930s.[34]) Given the counter-revolutionary nature of these politics, it is no surprise that “artists who wanted to wreck the hierarchies of class society” were denounced in favour of “appeal[ing] instead to the vanity of literary buffoons who thought they were going to write another War And Peace.”[35] Although Lukács himself did not speak at the Congress, his role from then on was to give intellectual credibility to the edicts emanating from the Kremlin on the subject of art, in much the same way as his fellow Hungarian Eugene Varga in the field of economics.[36]

Retrospectively, Lukács attempted to justify his position by claiming that his critical work was directed at two enemies, “the schematic deadlines and impoverishment of socialist literature” on the one hand and “those movements seeking salvation in following avant-garde schools” on the other. Indeed, he makes a point of asserting that avant-garde artists such as those seeking “a solution to aesthetic problems in an appropriation of the Joycean style”, far from being the inveterate anti-Stalinists that they pretended to be, “did not differ at all philosophically and politically from the crass naturalism and schematism of the Stalinist ‘construction novels’”.[37] Now, while it is true, as Ian Birchall says, that for Lukács, “the concept of ‘socialist realism’ is a more sensitive one… than it was for Zhdanov”, these claims amount to a post-hoc justification for his conduct which is not supported by a study of his writing of the time. The final section of The Historical Novel (1937), “a crude eulogy of third-rate novelists prepared to stand on anti-fascist platforms”, is standing reminder of how little he was prepared to risk deviating from the orthodoxy at this time.[38] Indeed, the notion of Critical Realism which he counterposed to Socialist Realism was only unveiled after Stalin was safely dead. Terry Eagleton has accurately stated the two-fold nature of Lukács’s endeavour: “Lukács’s task in the realm of aesthetics… was to sell bourgeois culture to the Stalinists while defending it from time to time on their behalf against an alarmingly ‘plebeian’ or ‘modernist’ Marxist art – against those, in short, whose attempted rupture with bourgeois cultural forms threatened the class collaborationism which the Soviet Union so desperately sought in order to protect its sovereignty from the violations of fascism.”[39] It should be clear from this outline of the political context in which Lukács worked that attempts to combine elements from his theory with that of Trotsky are unlikely to be successful. Both men were producing theories of art in a political context – the defeat of the Russian Revolution and the rise of Fascism – which profoundly shaped both their aesthetic and political perspectives, but in opposite directions. Their perspectives are therefore incompatible, at least in their implications for contemporary art, precisely because neither man saw his view of art as separate from his politics. Consequently, the writings of both are directed–implicitly in the case of Trotsky, explicitly in the case of Lukács – against the positions associated with the other.

Leon Trotsky.

Unlike Lukács, there were only two moments in his career as a revolutionary that Trotsky paused, as it were, to consider questions of art in some detail, as opposed to the occasional reviews and diary entries which he made throughout his life. In both cases the contexts in which these discussions took place can be no more dispensed with than they can in the case of Lukács. What were they? The first was an intervention, as a leading member of the Soviet republic then at the height of his personal power, in debates on the future direction of artistic production, post-revolution, post-civil war and in the period of relative calm following the introduction of the New Economic Policy. The second was a series of appeals, by a slandered and powerless exile, to rally artists around a revolutionary programme in a situation where, in the face of the coming war, the majority had embraced Stalinism as the only alternative to Fascism. The emphasis is therefore different in each case, but it is a tribute to Trotsky's great integrity as a thinker, however, that certain themes remain constant.

Literature And Revolution (1923), the central work from the first period, is best known for denying both the possibility of a working class culture under capitalism (because the economic and ideological subordination of the working class would prevent such a development) and the necessity for one under socialism (because the revolution would lead the way to a truly human, rather than class-based culture). This position – or at least the first element of it – was in fact the orthodoxy within the Bolshevik Party, although nowhere else expressed with such literary brilliance: of the Bolshevik leaders, only Bukharin was committed to the idea of a new proletarian culture arising in post-revolutionary Russia.[40] Lenin sometimes suggested that a proletarian culture could be built; although he was always careful to say that this could only be done with the materials inherited from bourgeois society:

We shall be unable to solve this problem [of proletarian culture] unless we clearly realize that only a precise knowledge and transformation of the culture created by the entire development of mankind will enable us to create a proletarian culture. The latter is not clutched out of thin air; it is not an invention of those who call themselves experts in proletarian culture. That is all nonsense. Proletarian culture must be the development of the store of knowledge mankind has accumulated under the yoke of capitalist, landowner and bureaucratic society.[41]

Those who detect a note of heresy here will no doubt be appalled to know that elsewhere Lenin transgresses still further; actually suggesting that nations contain more than one culture!

The elements of democratic and socialist culture are present, if only in rudimentary form, in every national culture, since in every nation there are toiling and exploited masses, whose conditions of life inevitably give rise to the ideology of democracy and socialism. But every nation also possesses a bourgeois culture (and most nations a reactionary and clerical culture as well) in the form, not merely of “elements”, but of the dominant culture.[42]

The point which Lenin is making here is that while there may be no such thing as a proletarian culture, the proletariat does have a culture, which is not identical to that of the bourgeoisie, even though it exists in the context of capitalist society and the dominant bourgeois ideology. This is an argument for another day; it should be apparent, however, that a view which labels every cultural event in the world for the last 200 years or more as “bourgeois culture” and nothing else is not to be taken seriously.

At first glance this position may seem to be compatible with that of Lukács, who wrote of “sectarian communist intellectuals [who] often fall for the dream of a ‘proletarian culture’, for the idea that a ‘radically new’ socialist culture can be produced, by artificial insemination as it were, independent of all traditions (proletcult)”.[43] Trotsky was, however, concerned with more than arguing that the artistic traditions of the bourgeois be made available to Russian workers and peasants, or even – true though it was – for the necessity for them to absorb those traditions as a prerequisite for further cultural progress. His work is also a defence of the autonomy of art from determination by either Party or State, a point that was of particular importance since by that time these were becoming increasingly indistinguishable in the USSR. Trotsky was always at pains to not to prescribe any artistic form to the exclusion of another: “The struggle for revolutionary ideas in art must begin once again with the struggle for artistic truth, not in terms of any single school, but in terms of the immutable faith of the artist in his own inner self.”[44] In particular, although he did not privilege modernism as the only appropriate form for contemporary artists, neither did he regard it as the twilight outpourings of a decadent bourgeoisie, or he would scarcely have been found consorting, as he did, with such committed modernists as Diego Rivera and Andre Breton.

In a brief and confused discussion of Literature And Revolution Lukács accuses Trotsky of believing both that art had to be of a propagandist nature under capitalism and that it would be devoid of class content (“pure art”) after the revolution: “Contrary to ‘propaganda’ (in which support of something means its idealist glorification, while opposition to it involves its distortion)... partisanship achieves the standpoint that makes possible the cognition and creative portrayal of the entire process as the summed-up totality of the real motive forces, as the perpetual, ever-higher reproduction of its underlying dialectical contradictions.”[45] We are also told of theories “devised in order to erect a Chinese wall between the classical past and the present and so to deny the Socialist character of our present – day culture a la Trotsky”.[46] Even the brief summary of Trotsky's views given earlier should indicate that Lukács had either failed to understand what the former had written, or was unable for political reasons to honestly engage with it. Given that Lukács was one of the most gifted men of his generation, the latter explanation seems more likely. Nevertheless, could there be deeper levels of agreement between the two men, lurking beneath the political divisions of the time? After all, Trotsky famously wrote: “A work of art should, in the first place, be judged by its own law, that is, by the law of art.”[47] And here is Lukács in 1956: “Art too is governed by objective laws. An infringement of these laws may not have such practical consequences as do the infringement of economic laws; but it will result in work of inferior quality.”[48] But this is precisely what Lukács, with his endless edicts on what art can and cannot be, never allows in practice: “While traditional critical realism transforms the positive and negative elements of bourgeois life into ‘typical’ situations and reveals them for what they are, modernism exalts bourgeois life's very baseness and emptiness with its aesthetic devices.”[49] Compare Trotsky on Celine's Journey To the End Of The Night, a book which certainly reveals the baseness and emptiness of bourgeois life, although it would violate the language to say that it exalts in it: “Though he may consider that nothing good can generally come from man, the very intensity of his pessimism bears within it a dose of the antidote.”[50] The openness of this judgement, its awareness of the different possibilities which art possesses for representing life, is in stark contrast to the closure which Lukács seeks to impose.[51]

It is, however, not enough to point out the Stalinist politics which inform the Lukácsian position and think that settles the matter. In due course I will quote Bertolt Brecht approvingly and it can hardly be denied that was also a Stalinist (although one far less centrally involved in propagating the Popular Front line). Nor is it enough to identify his differences with Trotsky, since it may be possible to salvage elements from Stalinist theory in the same way as we can from that of the bourgeoisie. How far – if at all – is this true of Lukács? If some individual judgements by Lukács can indeed be sustained, his theory as a whole cannot be similarly endorsed.

The Critique of Critical Realism

The trouble with the later Lukács, as Parkinson suggests, is largely the result of his abandoning or reversing the positions adopted in History and Class Consciousness and other works written around the same time. And these involve literary positions, in addition to more those of a more general philosophical nature. Take the person of Balzac himself. At the time Lukács was writing History and Class Consciousness, he paused to reflect on the great man’s reputation in the German party press:

For Balzac – just like the great 18th century English writers (Sterne, Smollett, Fielding), but keeping pace with the rapid intervening development – was the literary expression of the ambitious, progressive bourgeoisie. … Since… he was the literary expression of a rising social stratum, the totality of society and individual fate, a vision of the world and literary depiction were not separate matters for Balzac in the way they were for writers belonging to the bourgeoisie in decline (ideologically); unlike Balzac, these writers were unable to find the unifying element of their work in the life of society, in the very literary material, and had to try and replace it with theory, extraneously. … today we cannot yet foresee what stance the proletariat will adopt to a Balzac who has now become a wholly historical figure. If it has the leisure and the opportunity to re-live its own internal history on a conscious level, then Balzac’s oeuvre – a singular totalising representation of an entire age – will probably meet with deeper understanding than Balzac ever succeeded in finding in his own class, which fled increasingly from self-understanding.[52]

There are obvious continuities here with his later work, but these comments also contain a different emphasis in at least two respects. First, in the authors with which Lukács compares Balzac: whatever else may be said about Sterne’s The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, it is not a realist novel in any sense that the later Lukács would have recognised. Indeed, given that it is largely about the process of writing a novel it has some claim to be the first modernist work in the English language – in 1767. Second, in that he does not insist that we can lay down in advance the future attitude of the proletariat towards great realists such as Balzac, or, by implication, towards any artists of the bourgeois epoch.[53] In other words, in contrast to his later incarnation, the early Lukács had both a far broader conception of what counted as the “literary expression” of the rising bourgeoisie and far less certainty over how the proletariat would respond to it. The abandonment of these positions meant that the work of the later Lukács is characterized by theoretical weakness in four related issues; the adequacy of totality as a measure of artistic achievement (as opposed to being an aid to historical or social analysis), the distinction between art and politics, the accuracy of the historical link which he draws between realism (as he defines it) and the development of the bourgeoisie, and the appropriateness of his definition of realism.

(i) Art and Totality. Lukács argues that the key distinction between realist authors (such as Thomas Mann) and their modernist successors (such as James Joyce) is the ability of the former to convey the totality of the social world and the inability of the latter to convey anything but the fragmented experience of that world.[54] Now, as Terry Eagleton has pointed out, the view that modernist work is simply unmediated subjective “experience” is untenable: “Expressionist and surrealist art, need it be said, are every bit as much constructed as Balzac; we are judging (if we need to) between two different products of ideological labour, not between ‘experience’ and the ‘real’”.[55] More important, however, is the fact that the later Lukács uses the notion of totality quite differently than in History and Class Consciousness. Terry Lovell notes: “In [History and Class Consciousness] adoption of the viewpoint of the proletariat through active involvement in its political struggles was a condition of realism and truth. In the essays on art, it is the production of realism which places artists on the side of the proletariat, without the inconvenience of actually offering themselves at the barricade.”[56] This is disabling enough, but what is less often noted is that it is possible because the very notion of “totality” has undergone a transformation. Here is Lukács in 1923:

The totality of history is itself a real historical power – even though one that has not hitherto become conscious and has therefore gone unrecognised – a power which is not to be separated from the reality (and hence the knowledge) of the individual facts without at the same time annulling their reality and their factual existence. It is the real, ultimate ground of their reality and hence also of their knowability even as individual facts. … integration in the totality (which rests on the assumption that it is precisely the whole of the historical process that constitutes the authentic historical reality) does not merely affect our judgement of individual phenomena decisively. But also, as a result, the objective structure, the actual content of the individual phenomenon – as individual phenomenon – is changed decisively.[57]

As far as analysis of capitalism is concerned, this is very well said, and for historical and social analysis it should be a model for Marxists.[58] Can it, however, be taken as a model for art in general, or even for literature in particular? The later Lukács believed that it could:

[Totality] does not mean that every work of art must strive to reflect the objective, extensive totality of life. The totality of the work of art is rather intensive: the circumscribed and self-contained ordering of those factors which objectively are of decisive significance for the portion of life depicted, which determine its existence and motion, its specific quality and its place in the total life process. In this sense the briefest song is as much an intensive totality as the mightiest epic.[59]

Lukács is making the same point about art as he made earlier in relation to historiography, but the two are not the same.[60] At the Soviet Writer’s Congress of 1934 Karl Radek used sub-Lukácsian positions to argue that writers must show “the whole life of his characters”. But, as James T. Farrell pointed out in response: “Joyce did not treat the whole life of the petty bourgeoisie. No writer can succeed in showing all of life nor all of one class in a book or even in many books”.[61] What Joyce did succeed in showing was highlighted by George Orwell in his great essay, “Inside the Whale”:

The truly remarkable thing about Ulysses, for instance, is the commonplaceness of its material... his real achievement has been to get the familiar onto paper. He dared – for it is a matter of daring just as much as of technique – to expose the imbecilities of the inner mind, and in doing so he discovered an America which was under everybody's nose. Here is a whole world of stuff which you have lived with since childhood, stuff which you supposed to be of its very nature incommunicable, and someone has managed to communicate it. The effect is to break down, at any rate momentarily, the solitude in which the human being lives.[62]

Breaking down “the solitude in which the human being lives” may not be the only function of art, but it is an important one which depends on representing, through the mediations of artistic production, the experience of the social world.

(ii) Art and Politics. As we have seen, Lukács, like all serious Marxist critics, follows Engels in arguing that the critical power of a particular work does not necessarily depend on the social class, political beliefs or even conscious aims of the artist, since there may be a divergence between these and what actually results from the process of artistic production. Engels originally made this point (known in subsequent Marxist discussions as the “discrepancy” theory, after the discrepancy between the beliefs of the artist and what they reveal in their work) during a discussion of Balzac, who, although not himself an aristocrat, supported the royalists between 1830 and 1848 and, when they proved incapable of reversing the verdict of the French Revolutions, turned to his own personal brand of authoritarianism. Balzac was therefore – like Walter Scott, his predecessor and another great hero of classical realism – a reactionary even in the context of the bourgeois politics of his own time. Nevertheless, Engels thought highly of their work, noting of Balzac that it told him more about the nature of French society “than from all the professed historians, economists and statisticians of the period together.”[63] It is also worth noting, however, that according to the testimony of both Karl Kautsky and Paul Lafargue, Marx admired Balzac as much for the prophetic quality of his work as his depictions of near-contemporary French society, particularly his ability to see in embryo the social types who would only become fully developed after his death in 1850.[64]

The “discrepancy theory” was not presented by Engels as relevant only to realist art – the term would have been unknown to him in any case – but as a general proposition. Lukács appears to share this view: “The practical political conclusions drawn by the individual writer are of secondary interest.” This sounds promising, but it turns out to mean precisely the opposite of Engels’ position: “What matters is whether his view of the world, as expressed in his writings, connives at that modern nihilism from which both Fascism and Cold War ideology draw their strength.”[65] What Lukács is doing here is not simply raising the double standard which demands that modernism attain a level of political correctness never made of realism, but something more subtle.[66] He is claiming that realist art, whatever the political beliefs of the artists (i.e. even if they are reactionary), can reveal the underlying nature of bourgeois society, but that modernist art, whatever the political beliefs of the artists (i.e. even if they are revolutionary), can never do this, because it can only show the surface world of fragmentary experience. Moreover, this fragmentary world view unwittingly lends support – or in some cases positively endorses – ideologies of reaction, including the most extreme of all: Fascism.

This demonstrates a complete misunderstanding of what is specific to art as opposed to politics. As Eugene Lunn points out, the effect of this analysis is to “reduce literature to a mere repetition of an era’s characteristic ideological positions, which it derived from the historical position of the dominant class.” While Lukács avoids “crude economic determinism”, he substitutes the “passive reflection of social categories”: “There is no mediation of the social relations by the forces of production of which literary techniques are a part. Form is merely an expression of objective content. In epistemological as well as productive terms, the artist’s work is superfluous.”[67]

The Waverly novels of Scott and La Comedie Humaine of Balzac are works of great value to us, but that value is reduced if we expect them to reinforce political views which we already hold. Engels did not intend other socialists to approach literature – or any art form – solely, or even primarily, in this spirit, which is equivalent to saying that art is meaningful when it contains, at least implicitly, an analysis with which socialists can agree, although in ascribing this value we will be good enough to overlook the actual views of the artist concerned. Why bother with art at all then, if its purpose is the same as that of politics? The purpose of Marxist analysis in economic, social or political life is to reveal, in precise detail, how capitalism works, what the consequences of its continued existence are and what forces can be mobilised to bring it to an end: not for theoretical reasons, but to hasten the occurrence of the latter event. This cannot be the function of art. As Trotsky wrote: “If I say that the importance of The Divine Comedy lies in the fact that it gives me an understanding of the state of mind of certain classes in a certain epoch, this means that I transform it into a mere historical document, for, as a work of art, The Divine Comedy must speak in some way to my feelings and moods.”[68] Greenberg once wrote, using the same example:

That The Divine Comedy has an allegorical and analogical meaning as well as a literal one does not make it necessarily a more effective work of literature than the Illiad, in which we fail to discern more than a literal meaning. Similarly, the explicit comment on a historical event offered by Picasso's Guernica does not make it necessarily a better work than an utterly “non-objective” painting by Mondrian that says nothing explicitly about anything.[69]

I will question in the second part of this article the assertion that the paintings of Mondrian and his contemporaries “say nothing about anything”, but the general point, that the quality of a work of art cannot be determined on the basis of either its subject matter or their attitude of the artist towards it, is well made. Indeed one can go further and claim that intrusion of explicit politics actually has the effect of negating art. The point was made in ferociously formalist terms by Valentin Volosinov in Russia during the 1920s:

Aesthetic communication, fixed in a work of art, is entirely unique and irreducible to other types of ideological communication, such as political, the juridical, the moral, and so on. If political communication establishes corresponding institutions and, at the same time, juridical forms, aesthetic communication organises only a work of art. If the latter rejects this task and begins to aim at creating even the most transitory of political organisations or any other ideological form, then by that fact it ceases to be aesthetic communication and relinquishes its unique character.[70]

Part of the difficulty is that, if we reject the possibility that proletarian art exists or can exist under capitalism (as I think we must), then there is a tendency to assume that art under capitalism must therefore be “bourgeois”. What might this mean? A narrow definition would include those works of art which are directly produced by the bourgeoisie themselves: in other words, virtually nothing. A broad definition would include those works of art which are produced as commodities for the market: in other words, virtually everything. Neither of these definitions is particularly helpful. On the one hand, members of the bourgeoisie – even defined more broadly than the owners and controllers of capital – are not, on the whole, noted for making personal contributions to artistic production. On the other, many works are bought and sold which oppose the system that has made them commodities. Eagleton has noted how both cultural elitists and cultural populists “confuse ‘bourgeois culture’, in the sense of doctrines like possessive individualism which are inherently of that origin, with values like the appreciation of Verdi, which by and large have been confined to that class but have no inherent need to be.”[71] A more sensible approach would take ideology as the starting point.

It is in this context that we must return to the concept of totality, but in terms of bourgeois theory, rather than bourgeois culture, in the first instance. Let Adam Smith stand for bourgeois theoreticians before the global triumph of the system. When Smith completed The Wealth of Nations in 1776 capitalism did not exist in most of the world outside the United Netherlands and England, and was only in the process of being introduced in the Lowlands of his native Scotland. A world in which capital dominated was still only an aspiration which could only be realised by the most clear-sighted scientific assessment of how it had already triumphed, and of how these successes could be replicated elsewhere, not least in Scotland itself. In short, an awareness of historical and social totality was a necessity for Smith and the other thinkers of the Scottish Enlightenment. As the bourgeoisie consolidated in Britain and the world system began to take shape, however, the emergent working class movement began to emphasise those aspects of Smith critical of the bourgeoisie, the work of Smith was presented in such a way as to remove its dangerous critical edge: “one the one hand, defenders of the status quo stripped Smith’s economic theory of its commitment to rising employment and wages (and hence of its ethical dimension) in order to justify the ill fortunes of labourers as necessary and inevitable; on the other hand, critics of emerging industrial capitalism used Smith’s theories of growth and distribution in order to indict poverty and the factory system”.[72] If the latter ultimately led to Marxism, the former led to a position which Marx himself characterised as “the knell of scientific bourgeois economics”: “It was henceforth no longer a question of whether this or that theorem was true, but whether it was useful to the capital or harmful, expedient or inexpedient, in accordance with police regulations or contrary to them. In place of disinterested inquirers there stepped hired prize-fighters; in the place of genuine scientific research, the bad conscience and evil intent of apologetics”’[73] It was the early Lukács who best explained the reason for this process:

For the bourgeoisie was quite unable to perfect its fundamental science, its own science of classes: the reef on which it foundered was its failure to discover even a theoretical solution to the problem of crisis. The fact that a scientifically acceptable solution does exist is of no avail. For to accept that solution, even in theory, would be to tantamount to observing society from a class standpoint other than that of the bourgeoisie. And no class can do that – unless it is willing to abdicate its power freely. Thus the barrier which converts the class consciousness of the bourgeoisie into “false” consciousness is objective: it is the class situation itself. It is the objective result of the economic set-up, and is neither arbitrary, subjective nor psychological.[74]

The later Lukács transferred into the domain of culture the historical periodization in which Marx, Engels and his own earlier self saw the bourgeoisie abandon by 1830 the attempt to theoretically apprehend society as a totality. Much of what he writes on this subject is compelling and insightful, and the claim that there is a falling off in quality between the great realists and the mere naturalists can, I think, be defended.[75] The reasons which he gives for it, however, cannot. Late in his life Lukács wrote that: “The author of these essays subscribes to Goethe’s observation: ‘Literature deteriorates only as mankind deteriorates.’”[76] But, as Perry Anderson writes: “The basic error of Lukács's optic here is its evolutionism: time, that is, differs from one epoch to another, but within each epoch all sectors of social reality move in synchrony with each other, such that decline at one level must be reflected in descent at every other.”[77] Anderson rightly rejects this, arguing that transformations in culture do not simply occur in lockstep with those of the economic or the political; to imagine that they do is to ignore the distinction between the “immediate and mediated effects of the ‘economic structure’ upon the various social institutions” under capitalism to which Lukács himself had drawn attention in History And Class Consciousness.[78] There is theoretically no reason why great realist works should not be produced after 1848 and indeed they have been. Anderson gives the example of Anthony Powell’s novel sequence A Dance to the Music of Time, the first volume of which, A Question of Upbringing, was published in 1951, shortly after the centenary of 1848.[79] It is, however, possible to find proof of this in the work of the author whom Lukács rightly considered to have been responsible for pioneering the realist novel in its historical form: Sir Walter Scott.[80]

Many of the things Lukács has to say about Scott are of great interest, particularly in his discussion of the novels which are most frequently dismissed, such as Ivanhoe. But even leaving aside his notorious factual inaccuracies (most of which concern Rob Roy), there are major difficulties with his analysis, which arise not simply because of deficiencies in Lukács's understanding of the Scottish bourgeois revolution (which he shares with most Marxists), but his failure to understand Scott's relationship to that revolution. In his obsession with the discrepancy theory Lukács overlooks that the reactionary views that Scott holds are not overridden in his actual writings, but in fact shape their structure. Lukács notes of Scott that he takes a “centrist” position on important questions of “English” [i.e. British] history. In Old Mortality, for example, he endorses neither the religious radicals (the Scottish Covenanters) who continued to struggle against the absolutist state after 1660, nor the Stuart dynasty which sat at its apex. His heroes therefore constitute a moderate “third way” between revolution and reaction: “The artistry in his composition is thus a reflection of his own political position, a formal expression of his own ideology.”[81] Lukács wrote in The Historical Novel that Scott was attempting to reveal two aspects of British history in his work. First, that Scottish and English development was not a smooth upward ascent, but one punctuated by violent social upheavals. Second, that a middle way exists for these forces to resolve their differences: “He finds in English history the consolation that the most violent vicissitudes of class struggle have always finally calmed down into a glorious ‘middle way’. Thus out of the struggle of the Normans and the Saxons there arose the English nation, neither Saxon nor Norman”.[82] This is the theme of Ivanhoe, but the novel also works as extended analogy for the creation of both British and Scottish nations, with the Saxons and Normans standing in respectively for the Scots and the English in the case of the first, and for the Highland Scots and Lowland Scots in the case of the second. Scott is often seen as the last great figure of the Scottish Enlightenment, and in one sense this is fitting, since he had internalized its theory of historical change, and given it concrete artistic expression in his novels. In can, however, be just as usefully seen as the literary representative of the class of improving landowners, who were being replaced in the Scottish class structure by the manufacturers, who brought both factories and workers in their wake.[83] He admires both Union and Empire, but is unwilling to pay the price in the transformation of the Scottish social structure. Lukács writes that: “Scott himself lived in a period of English [sic] history in which the progressive development of bourgeois society seemed assured, and thus he could look back upon the crises and struggles of prehistory with epic calm.”[84] This is completely false.

Between 1815 and his death in 1832 Scott’s letters and diaries reveal a man increasingly hysterical with fear at the emergence of an organised working class movement, notably around the moment of the Scottish General Strike of 1820. Scott's literary version of the Scottish historical past was intended to convey the false impression that internal division was a thing of the past. For although national reconciliation had indeed taken place, class divisions were opening up which he saw no possibility of overcoming. This is one reason why Scott almost never discusses the contemporary world in his novels. (The Antiquary and St. Ronan’s Well are partial exceptions – not coincidentally – among his worst novels.) He is only comfortable writing about historical situations that have already been resolved, and for that reason protagonists on both sides can be equally celebrated. These novels do not passively reflect the historical rise of the Scottish bourgeoisie, but actively intervene in contemporary politics with an ideology of national and class unity.

Scott lived in a society that had reached by the 1790s the level of development which Western and Central Europe would reach by 1848. The British bourgeoisie, of whom he was an outspoken and politically active representative, met its 1848 in 1776 and 1792, and thereafter displayed the same hostility to democracy and fear of the working class that would become general in 1848. Scott was nevertheless able, in these circumstances, to originate and develop the realist novel in exactly the conditions which later Lukács claims were responsible for its decline. The answer to this apparent contradiction is to understand that the relation between the bourgeoisie and the novel (and indeed the other arts) is considerably more complex than he assumes: the bourgeoisie are neither directly responsible for producing art nor does art directly embody their class perspective.

The definition of realism which Lukács gives is quite specific to literature and this raises the question of the extent to which it can be generalised across the entire spectrum of artistic production. Some ill-considered comments on Schonberg apart, Lukács usually restricted himself to the discussion of writers, yet despite this refusal to engage with disciplines outside his professional specialism, he nevertheless made sweeping general statements about realism and modernism on the basis of literary developments alone. Now, while it is at least possible to compare Thomas Mann’s novel The Magic Mountain with James Joyce’s novel Ulysses on a formal level; it is not possible to compare The Magic Mountain with Jackson Pollock’s painting Autumn Rhythm. Considerations on the realist novel cannot be the basis of a discussion of modernist art – which includes not only literature, but painting, sculpture, architecture and cinema. A modernist painting can scarcely be expected to fulfil the same function as a realist novel; indeed, a realist painting cannot be expected to fulfil the same function as a realist novel – and in some key modernist disciplines – architecture, for example – there are styles which precede it, but no “realist” school with which comparisons can be made. In other words, even if we accept for the moment that Lukács makes a coherent case (which is not the same as a convincing case) for the decline of literature after the bourgeois revolution, the very way in which his categories are drawn from literature make that case difficult to extend to other mediums other than by assertion.

Take for example, the writings of the Russian Formalist Nikolai Tarabukin, Secretary of the Institute of Artistic Culture between 1920 and 1924, and participant in the debates over production art in general and Constructivism in particular. Tarabukin proposes a very different relationship between realism, naturalism and modernism than that offered by Lukács. Lukács sees a regression from realism (inner totality of social life) to naturalism (outer appearance of social life) to modernism (fragmented experience of social life), but for Tarabukin, realism is the “basic stimulus” for abstract Cubism, Suprematism and Constructivism:

I use the concept of realism in its widest sense and do not by any means identify it with naturalism, which is one of the forms of realism and, at that, one of the most primitive and naïve. Contemporary aesthetic consciousness has transferred the idea of realism from the subject to the form of the work of art. Henceforth the motive of realistic strivings was not the copying of reality (as it had been for the naturalists) but, on the contrary, actuality in whatever respect ceased to be the stimulus for creative work. In the forms of his art the artist creates its actuality, and for him realism is the creation of a genuine object which is self-contained in form and content, an object which does not reproduce the objects of the real world, but which is constructed by the artist from beginning to end, outside any projected lines extending towards it from reality.[85]

Tarabukin therefore defines modernism as a return to realism in opposition to naturalism, rather than, as Lukács does, as a further retreat from realism in succession to naturalism. As Lovell has written, “[r]ealisms are plural”, but share at least two characteristics: “firstly, the claim that the business of art is to show things as they really are, and secondly, some theory of the nature of the reality to be shown and the methods which must be used to show it”.[86] It might be more realistic, as it were, to see realism, not as a formal innovation expressive of a new historical consciousness, but as a portfolio or palette of different approaches which allow art to be, as Aleksander Vygotsky puts it “the cognition of life”, but which stretches back as far as Ancient Greek drama of Sophocles.[87]

Fredric Jameson once proposed that an accurate periodization of the development of cultural forms involved the category of a “Classical” period, corresponding to the feudal epoch, before the advent of realism: “the moment of merchant culture and of a Renaissance-style novella that is neither ‘realistic’ nor ‘modernistic’”.[88] In a later version of the same article he abandoned the suggestion, possibly defeated by the sheer range of forms which would have had to be incorporated into this one term.[89] Nevertheless, it seems a more helpful approach might be to consider that these forms of artistic production typical of the pre-capitalist or transitional period might themselves be forms of realism. Brecht certainly believed this, arguing that:

…writers as diverse as Hasek (author of The Good Soldier Schweik) and Shelley, Swift and Grimmelhausen, as well as Balzac, were great realists. All of them had used multiple means, including wild fantasy, the grotesque, parable, allegory, typifying of individuals, etc., for realistic purposes. These writers experimenting with new formal means to reveal a constantly changing social reality – now more necessary than ever – were not the real formalists.[90]

Indeed, long after the debates of the 1930s were over, Lukács effectively conceded the same point, writing that:

…in our opinion it is not necessary that the phenomena delineated be derived from daily life or even from life at all. That is, free play of the creative imagination and unrestrained fantasy are compatible with the Marxist conception of realism. Among the literary achievements Marx especially valued are the fantastic tales of Balzac and E. T. A. Hoffman.[91]

If Lukács had consistently held this position is difficult to see how he could have written the strictures on realism which fill the rest of his later work.

Endnotes

- Yates McKee, Strike Art: Contemporary Art and the Post-Occupy Condition (London: Verso, 2016), 7, 242.

- Fredric Jamieson, [1984], “The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism”, in Postmodernism: The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (London: verso, 1991), 3-4, 35-36. The term “postmodern” underwent several mutations of meaning before arriving at the current usage – a moment which probably coincided with the publication of The Postmodern Condition by Jean-Francois Lyotard in 1979. See Hans Bertens, The Idea of the Postmodern: A History (London: Routledge, 1995), 20-81 and Perry Anderson, The Origins of Postmodernity (London: Verso, 1998), 3-36.

- One of Greenberg’s followers, Michael Fried, did however invoke Lukács’ “great work” History And Class Consciousness to explain how “the dialectic of modernism in the visual arts has been to provide a principle by which painting can change, transform and renew itself” – a position which would no doubt have appalled the later Lukács. See [1965], “Three American Painters”, in Modern Art and Modernism: a Critical Anthology, edited by Francis Frascina and Charles Harrison (London: Harper and Row, 1982), 118.

- Alan M. Wald, The New York Intellectuals (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987), 206-208. One of Greenberg’s brothers, Sol, was a member of the Worker’s Party.

- John Newsinger, Orwell’s Politics (Houndmills: Macmillan, 1999), 89. Orwell’s relationship with Partisan Review is discussed in ibid, 90-100.

- Clement Greenberg and Dwight Macdonald, “10 Propositions on the War”, Partisan Review 8 (July-August 1941), 271-278 and Clement Greenberg [1940], “An American View”, in Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 1, Perceptions and Judgements, 1939-1944, edited by John O'Brian (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986), 38-41. The latter essay was originally published in the British magazine Horizon. Trotsky’s own position did more than simply point to the sympathy of the British and US ruling classes for Fascism, but also indicated how revolutionaries could use this to gain a hearing among the working class – a position which involved participating militarily in the prosecution of the war while arguing for trade union control of military policy. See, for example, Leon D. Trotsky [1939], “American Problems”, in Writings of Leon Trotsky [1939-40], edited by Naomi Allen and George Breitman (Second edition, New York: Pathfinder Press, 1973), 333-334.

- Clement Greenberg [1941], “Review of Rosa Luxemburg, Her Life and Work by Paul Frolich”, in Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 1, 77-79. This article includes an acute critique of a certain type of political hack, which Greenberg seems to have encountered in the Trotskyist as well as Stalinist camps: “…the followers of Lenin and Trotsky – like little men, aping the externals of those they follow – have cultivated in themselves that narrowness which passes for self-oblivious devotion, that harshness in personal relations and above all that desolating incapacity for experience which have become the hallmarks and standard traits of the Communist ‘professional revolutionary’. These men have served as organisers and agitators, they have shown admirable energy, devotion and capacity for self-sacrifice; but as political leaders in the larger sense they have been failures in every case and everywhere.” Ibid, 78.

- Marshall Berman [1985], “Georg Lukacs’s Cosmic Chutzpah”, in Adventures in Marxism (London: Verso, 1999), 194.

- John O’Brian, “Introduction”, in Clement Greenberg, Collected Essays and Criticism, vol. 1, xxvi-xxviii; Frances Stonor Saunders, Who Paid the Piper? The CIA and the Cultural Cold War (London: Granta Books, 1999), 198-199; Wald, The New York Intellectuals, 273.

- Susan Sontag [1964], “The Literary Criticism of Georg Lukács”, in Against Interpretation and Other Essays (London: Vintage, 1994), 86.

- Florence Rubenfield, Clement Greenberg: A Life (New York: Scribner, 1997), 257-258.

- Lukács also wrote a number of literary reviews for the KPD paper Die rote Fahne at the same time as he was writing History and Class Consciousness. Aside from being interesting in themselves they show significant divergences from the positions with which he became identified from the 1930s: I have cited some of these below, but am not suggesting that they constitute a fully developed alternative to his later work.

- The same is true of other Trotskyist writers cited below, like James T. Farrell and Meyer Shapiro, whose work similarly needs to be incorporated into Marxist tradition.

- In what follows I will use the term “the early Lukács” to refer to his work before 1929 and “the early Greenberg” to refer to his work before 1945.

- Georg Lukács [1937], The Historical Novel (Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, 1969), 22.

- Georg Lukács, Studies in European Realism (London: Merlin Press, 1950), 7.

- Ibid, 8.

- Ibid, 147.

- Georg Lukács, The Meaning of Contemporary Realism (London: Merlin Press, 1963), 19.

- Georg Lukács [1949], The Destruction of Reason (London: Merlin Press, 1980), 309.

- Lukács, Studies in European Realism, 140.

- Ibid, 169.

- Ibid, 43.

- Ibid, 134-137.

- Lukács, The Destruction of Reason, 309.

- Georg Lukács [1938], “Realism in the Balance”, in Aesthetics and Politics (London: New Left Books, 1977), 56-57.

- Lukács, The Meaning of Contemporary Realism, 109.

- George Parkinson, Georg Lukács (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1977), 89.

- Alex Callinicos, “Impossible Anti-Capitalism?” New Left Review II/2 (March/April 2000), 117.

- Michael Lowy [1975], “Lukács and Stalinism”, in Western Marxism: A Reader, edited by New Left Review (London: New Left Books, 1977), 74.

- Isaac Deutscher [1966], “Georg Lukács and ‘Critical Realism’”, in Marxism in Our Time edited by Tamara Deutscher, (Berkeley: Ramparts Press, 1971), 291.

- The major contributions to this Congress were republished as late as 1977 by Lawrence & Wishart, the publishing house associated with Communist Party of Great Britain, without any critical comment. The only person who comes out of the event with any credibility is Bukharin, in one of his last important contributions to Marxism. See Nikolai I. Bukharin, [1934], “Poetry, Poetics and the Problems of Poetry in the USSR”, in Nikolai Bukharin, Maxim Gorky, Karel Radek, Andrei Zhdanov and others, Soviet Writer’s Congress 1934 (London: Lawrence & Wishart, 1977).

- Ben Watson, Art, Class and Cleavage: a Quantulumcunque Concerning Materialistic Esthetics (London: Quartet Books, 1999), 57.

- Esther Leslie, Walter Benjamin: Overpowering Conformism (London: Pluto Press, 2000), 101.

- Watson, Art, Class and Cleavage, 58.

- Indeed, even Varga showed more independence of thought, arguing after the end of the Second World War that state intervention would enable the capitalist West to avoid economic crisis in future. For this heresy he was stripped of his official positions until his recantation in 1949. See Michael C. Howard, and John E. King, A History of Marxian Economics, vol. 2, 1929-1990 (Houndmills: Macmillan, 1992), 8, 77.

- Georg Lukács [1965 and 1970], “Preface”, in Writer and Critic (London: Merlin Press 1978), 8.

- Ian Birchall, “Lukács as a Literary Critic”, International Socialism, first series, 36 (April/May 1969), 37.

- Terry Eagleton, Walter Benjamin, or Towards a Revolutionary Criticism (London: Verso, 1981), 84.

- Donny Gluckstein, The Tragedy of Bukharin (London: Pluto Press, 1994), 66-76.

- Vladimir I. Lenin [1920], “The Tasks of the Youth Leagues”, in Collected Works, vol. 31, April-December 1920 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1966). 287.

- Vladimir I. Lenin [1913], “Critical Remarks on the National Question”, in Collected Works, vol. 20, December 1913-August 1914 (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1966), 21.

- Lukács, Studies in European Realism, 105.

- Leon D. Trotsky [1938], “The Independence of the Artist: a Letter to Andre Breton”, in Leon Trotsky on Literature and Art, edited by Paul N. Siegel (New York: Pathfinder Press, 1970), 124.

- Georg Lukács, “Propaganda or Partisanship?” Partisan Review, vol. 1, no. 2 (April/May 1934), 42, 45. It is a measure of the absurdities generated by Stalinist anti-Trotskyism that Literature And Revolution was referred to far more favorably by T. S. Eliot in 1948 than Lukács in 1934 – although had the latter known this it would have no doubt have only provided more “proof” of Trotsky’s objective support for Fascism, Royalism, etc. See [1948], Notes Towards a Definition of Culture (London: Faber and Faber, 1962), 89, note 1.

- Lukács, The Historical Novel, 52.

- Leon D. Trotsky [1923], Literature and Revolution (London: Bookmarks, 1991), 207.

- Lukács, Studies in European Realism, 117.

- Ibid, 68.

- Leon D. Trotsky [1933], “Celine and Poincare: Novelist and Politician”, in Leon Trotsky on Literature and Art, 202.

- More interesting than the futile attempt to find areas of common ground between Trotsky and Lukács might be the parallels between Trotsky and Benjamin. See Leslie, Walter Benjamin, 228-234 and Neil Davidson, How Revolutionary Were the Bourgeois Revolutions? (Chicago: Haymarket Books, 2012), 278-279.

- Georg Lukács [1922], “Balzac’s Posthumous Fame”, in Reviews and Articles from Die rote Fahne (London: Merlin Press, 1983), 5-7.

- The key word in the above quotation is “probably”. The fact is that we have no idea what will be of use to us under socialism. As Terry Eagleton writes: “It is neither the case that Sophocles will inevitably be valuable for socialism, nor that he will inevitably not be; such opposed dogmatic idealisms merely suppress the complex practice of cultural revolution.” See Walter Benjamin, 130. In another context Eagleton asks: “Who is cocksure enough to predict that medieval love poetry might not prove a more precious resource in some political struggle than the writings of Surrealist Trotskyists?” See The Illusions of Postmodernism (Oxford: Blackwell, 1996), 125. Alas, I (and probably most socialists) know comrades who are cocksure enough to predict exactly what will be our most precious resources in any future struggle.

- See, for example, Lukács, “Realism in the Balance”, 33-36.

- Eagleton, Walter Benjamin, 88.

- Terry Lovell, Pictures of Reality: Aesthetics, Politics, Pleasure (London: British Film Institute, 1985), 74. See also Birchall, “Lukács as a Literary Critic”, 38.

- Georg Lukács [1923] “Reification and the Consciousness of the Proletariat”, in History and Class Consciousness: Essays in Marxist Dialectics (London: Merlin Press, 1971), 152.