When Wes Craven died recently, most obituaries focused on his successful money-making Nightmare on Elm Street and Scream series. Very few even mentioned his earlier independent commercial films The Last House on the Left (1971) and The Hills have Eyes (1977), both of which had higher-budget but undistinguished remakes. These early films belonged to the exciting and innovative decade of the 1970s—when the ignominy of American defeat in Vietnam and crisis of confidence in the White House stimulated many iconoclastic and radical commercial films now conspicuous from the mainstream in their very absence. Craven then belonged to a group of innovative talents such as Brian DePalma, Tobe Hooper and Larry Cohen, all of whom took over familiar generic conventions for their own particular critical perspectives. While DePalma achieved a problematic Hollywood ascendency before making a film critical of the Iraq War and Hopper fell into inactivity, it is perhaps the little known name of Larry Cohen who has left the most challenging legacy. This is despite the fact that he is still at the height of his creative powers, and constantly writing screenplays that Hollywood finds “too hot to handle," many of which are available to read on his Web Site.

Born in 1941, the young New Yorker grew up with comics and movies, attended City College of New York (CCNY), and became the youngest television writer at the tail end of the Golden Age of American television, contributing scripts to socially relevant 1960s New York based series such as The Defenders, The Nurses, as well as contributing what is perhaps the best contribution to the British television series Espionage, “Medal for a Turned Coat,” that contained a striking psychological interrogation of the real motives behind a supposed hero who, in reality, was little better than a “hollow man.” Fritz Weaver’s performance in the title role added distinction to what was already a remarkable teleplay. Cohen then moved to Hollywood becoming the creator of pilots, especially those that became established television series such as Branded and The Invaders before turning to write film screenplays. Dissatisfaction with the way several directors treated his work led to his decision to become the ultimate auteur fully in control of his material. Written, Produced, and Directed by Larry Cohen parallel credits to early works by Samuel Fuller. Larco was Cohen’s equivalent to Fuller’s Globe Productions.

Bone (1972) was his first independent feature. Variously retitled Beverly Hills Nightmare, Dial Rat for Terror, and Housewife by commercial distributors the film fitted into no known category—narrative or independent film. It functioned as an attack on the consumerist mentality pervading society, with the supposed threatening figure of its title character played by Yaphet Kotto in a striking performance affecting self-made Beverly Hills executive (Andrew Duggan) and his selfish wife (Joyce Van Patten). Bone may or may not be someone conjured up by their own distorted psychological mechanisms. The couple exist in a state of denial with an absent son they state is an MIA but who in reality is in jail for a drug offence and who may be the actual sorcerer’s apprentice in this cinematic nightmare. The film ends inconclusively leaving the viewer with no viable solution except that of a profound disturbance that could lead to a questioning of the premises behind capitalist society.

These elements are unconscious in the mind of Larry Cohen but they also operate as parallels to the type of independent cinematic operations of Orson Welles who often leaves viewers in states of disequilibrium leaving them to arrive at whatever conclusions they choose to select consciously and intelligently. Cohen is often associated with fantasy or the horror genre but denies that his films are confined to the latter realm. Instead, they are radical allegories of American society directed by someone who chooses the framework of commercial narratives into which he inserts dark and satiric components having much in common with those of Alfred Hitchcock, a director he admired, knew, and worked with on one occasion. Despite dismissal by many on the grounds of a technique having much in common with the comic strip, his works really demand the careful attention of an alert viewer, the type of viewer Roger Ebert regards as the ideal perceiver in his Citizen Kane DVD audio-commentary. Like Hitchcock films, appearances are deceptive and the same is true for any Larry Cohen film whether they encompass acting, content, and style.

After writing a script for Sammy Davis Jnr which the actor retreated from, Cohen made one of the most remarkable films in the so-called “Blaxploitation” cycle, one acclaimed by Public Enemy at the end of “Burn, Hollywood Burn.” This was Black Caesar (with deliberate parallels to Little Caesar and Robert Warshow’s essay on “The Gangster as Tragic Hero”). Yet, as well as critiquing racism, Cohen’s treatment left no room for identity politics since it revealed its hero played by Fred Williamson as liable to contamination by the capitalist system as any Edward G. Robinson, James Cagney, and Paul Muni. Its ending was appropriately bleak. Yet, its popularity led to a sequel Hell Up in Harlem resurrecting the hero to avenge himself on the system (whether employed by black or white) with an ending implicitly questioning its hero’s integrity. It was shot on weekends during the filming of It’s Alive (1973).

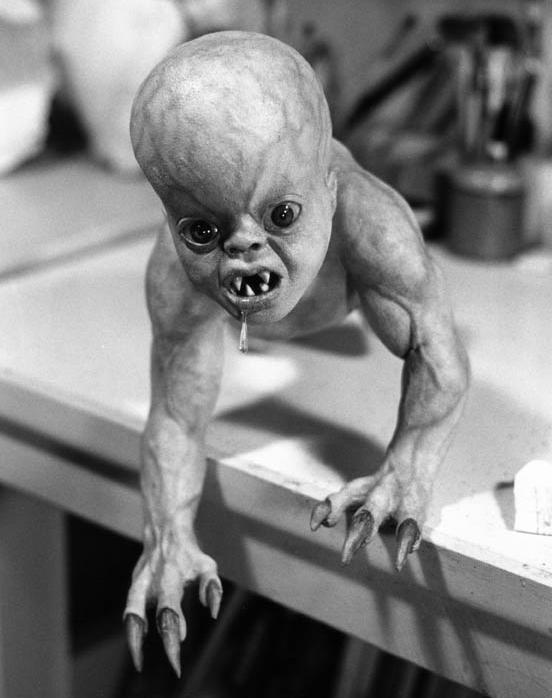

While indelibly associated with the 70s family horror film critical of American society, It’s Alive operates on a much wider canvas. While its monster baby may be the result of tensions within the nuclear family, Cohen also suggests that the medical and corporate food industries may also be responsible for a new genesis superseding that of the Old Testament book. The leaves open a diverse number of possibilities not necessarily confined to the horror genre. If Rosemary Jackson once defined Fantasy as a Literature of Subversion, Cohen takes several popular genres such as fantasy and horror making them his unique cinema of subversion. The sequel It Lives Again (1978) actually names two new monster babies Adam and Eve cared for by Cohen’s favorite bad guy Andrew Duggan (who plays roles far removed from his Ben Cartwright version in the Western TV series Lancer) aided by none other than the familiar Lemmy Caution figure of Eddie Constantine who looks like he suffers from a transatlantic nightmare hangover in this film. The film opens with new expectant parents receiving an Annunciation from the father in the previous film, John Ryan, now functioning like a perverse Angel Gabriel.

Cohen’s iconoclastic interests appear also in God Told Me To (1976) that merges science fiction with the religious movie in its narrative of an androgynous alien messiah who arrives on earth lacking his real identity but believing his is a New Messiah by using gay men to attack families and assault New Yorkers as well as employing corporate executives for his end. The climax comes when Tony Lo Bianco’s Peter Nicholas realizes that his repressed Catholic guilt anxieties stems from the fact that his new-found family values are actually more inclusive and subversive than the ones he formerly adhered to.

The Private Files of J. Edgar Hoover (1977) is Cohen’s most explicitly radical attack on the premises of American society and the founder of the surveillance society dominating us all today. Broderick Crawford’s Hoover is both political monster and contaminated tragic hero, the star of the 50s TV series Highway Patrol both victimizer and victim. Depicted in a comic book style representing one of the popular cultural elements this “Great Leader” used to boost his own form of deity, modeled on the notorious Hoover bio-pic The F.B.I. Story (1959) featuring a galaxy of former Hollywood stars, one of whom (Lloyd Nolan) had appeared opposite James Cagney in the Warner Bros. 1935 Hoover homage G-Men, the film presents twentieth-century American society as corrupt from top to bottom. Hoover earned the respect of the later Robin Wood as “perhaps the most intelligent about American politics ever to come out of Hollywood.”

When independent production companies, drive-ins and non-corporate owned movie houses flourished so did Cohen’s films. But things changed in the 80s.Corporate forces regained control of Hollywood aided by a former movie-star FBI informer President who ignored the 1948 Supreme Court ruling separating production, distribution, and exhibition. Cohen’s films still received theatrical release but VHS also allowed him another market for his talents.

Q-The Winged Serpent (1982) saw the first of his four collaborations with Michael Moriarty), one as unique as Hitchcock with James Stewart and Cary Grant, and Scorsese with Robert DeNiro but operating on more iconoclastic levels. Dealing with the return of Quetzalcoatl to a New York unprepared for his resurrection, the film combined comedy, suspense, and drama. The Stuff (1985) re-united director and star in an attack on the Food and Drug Administration and American consumerist culture always ready to subordinate public health and safety to profit. Despite its low-budget production, It’s Alive III presented Moriarty as the sympathetic father of a dangerous monster baby pleading for its life in a poignant courtroom scene before judge McDonald Carey who orders protection of the species on an island that will soon be invaded by hired assassins from the company responsible for the mutation. The film ends on a very positive note with formerly separated husband and wife (Karen Black) driving away into the sunset after rescuing their grandchild. Cohen’s humanity shines through this film especially in the scene when Cubans show Moriarty that they also are not monsters.

A Return to Salem’s Lot represented the last 1980s teaming of actor and director in a reworking of Stephen King’s novel featuring Samuel Fuller as a Jewish Nazi hunter investigating a village whose vampires represent predatory aspects of American life.

Other Cohen films and screenplays could be mentioned but they are well-documented elsewhere. After attempting his own franchise series Maniac Cop ruined by bad direction, Cohen’s last distributed theatrical feature was Original Gangstas (1996). Featuring former stars of Blaxploitation such as Fred Williamson, James Brown, Richard Roundtree, Pam Grier, and y others, Cohen shot the film in Gary, Indiana. Once a thriving industrial community, it was now a victim of the urban decline created by Reagan, Bush, and Clinton. Choice of location was not accidental. Thanks to Cohen’s direction, the film elicited dignified performances from every talent involved functioning both as entertainment and social comment.

The latter part of Cohen’s career has seen neglect by a conformist and conservative Hollywood industry afraid to take a chance on the uniquely critical elements of his work. Like Fuller, Cohen is also a real independent. Looking at many of his original screenplays and seeing the ways in which they have been destroyed by ruthless producers and directors could make one weep. His screenplay “Invasion of Privacy”, affirming a woman’s right to choose led to a dire TV movie version. Like others, it was a story dealing with real social issues Hollywood now fears to touch. But this is not the time to dwell on these problems. Cohen himself remains active and resilient constantly writing every day. He has put several unproduced screenplays on his Web Site for readers to create imaginatively the film he has written. My personal favorite is “The Man who Loved Hitchcock”. Based on a project that would have cast Peter Ustinov as “The Master of Suspense”, it is the devoted work of an artist who knew both Hitchcock and Bernard Herrmann (who scored It’s Alive) presenting a poignant reconciliation between two great talents whom corporate Hollywood managed to separate, and far better than the two Hitchcock travesties released a few years ago. Fortunately, we have DVD and Film Festivals to celebrate the work of this unique talent who could still amaze us if Hollywood would ever take the chance of allowing him full control of his work and unqualified support.

Tony Williams is the author of Larry Cohen: The Radical Allegories of An American Filmmaker, second edition, Mcfariland & Co., 2014.