In the face of profound social, political and economic tragedy, it has often been the case that popular musicians, out of a sense of solidarity, put out a song to capture the moment and inspire the movement. It is often the case, by virtue of historic specificity, that these songs don’t date well, their universality caught in the particularity of a given moment. There are a few songs, however, that have outlasted their origins and continue to resonate. Neil Young’s “Ohio,” Bruce Springsteen’s “American Skin (41 Shots)” and, most recently, in the face of the spate of police murder of Black youth, and in solidarity with the Black Lives Matter movement, Prince’s “Baltimore.”

Reminiscent of mid-period Prince and the Revolution, it combines a funkish shuffle in a minor key with vaguely country/western sounding acoustic and electric guitars. The lyrics, while angry, are more sad and resigned than anything else: “Nobody got in nobody's way… So I guess you could say it was a good day… At least a little better than the day in Baltimore… If there ain't no justice then there ain't no peace.” Never an explicitly political artist, except perhaps in what he signified and his charmingly naïve “Ronnie Talk to Russia,” urging the new US president to end the Cold War, Prince nevertheless was compelled by circumstances to write a song for the moment, and it will remain relevant, even if the battle is ever won.

And it was in many ways his swan song.

The Reaper has been busy in 2016, Prince is dead at 57 years old and only recently on the road doing a well-received solo piano tour. Looking back at nearly four decades of hybridizing rock, funk and dance music, there can be no doubt that the man was a pioneer, sonically, aesthetically and as an artist who stood up and fought back against a music industry that alienated his labour. It’s damned-near impossible to think of an artist like Prince on any of these levels, as he is likely one of the last artists coming out of the guitar/bass/drums pre-1980 world to have virtually invented a new form of music. Starting out playing in funk bands, he became part of a vibrant Minneapolis music scene in the late seventies, a time in which an audience existed for both Black artists like Prince and Morris Day and white punk bands like the Replacements and Husker Du. Like Thin Lizzy’s Phil Lynott in Ireland, Prince never was seen as a “Black guy doing white music”, he was simply a musician in a red-hot and innovative music scene unaffected by coastal snobbery or Southern reaction.

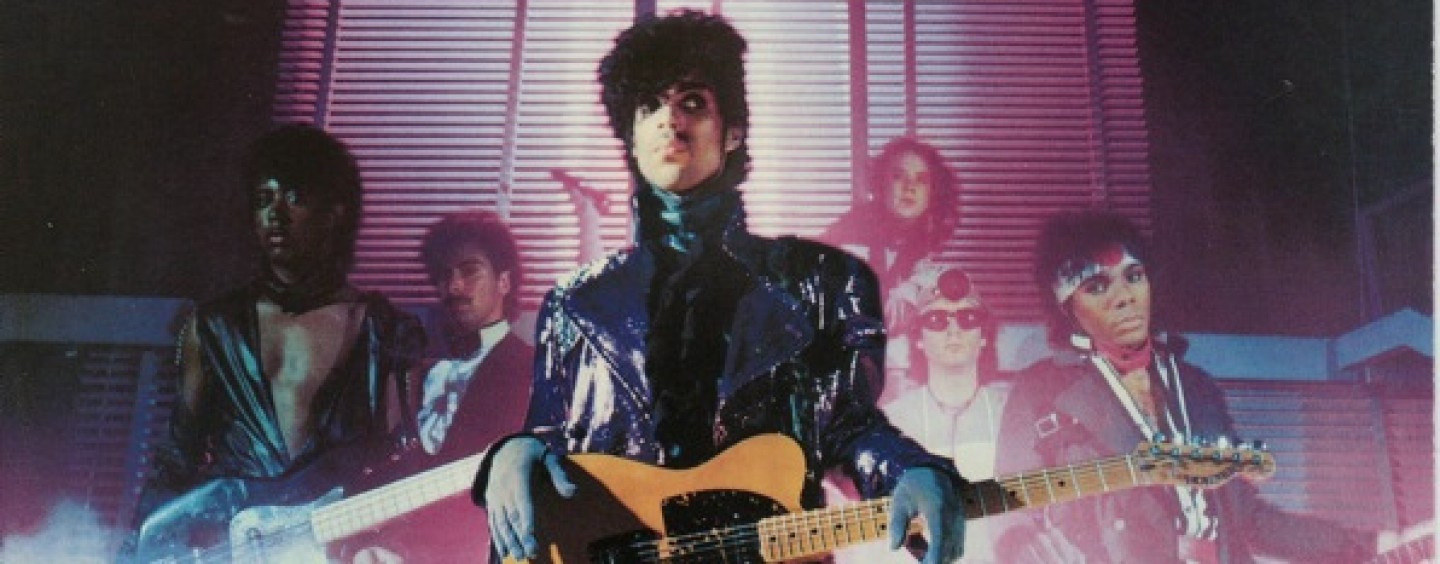

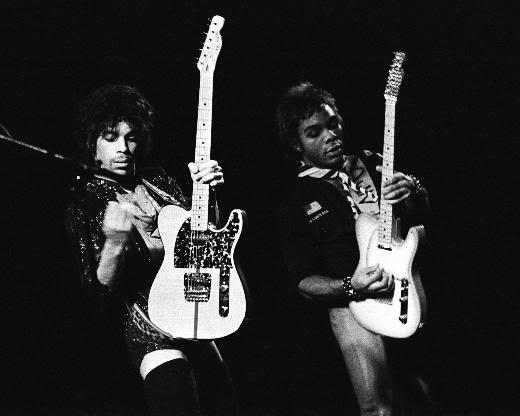

While developing his live chops as a master at the Telecaster, the theatricality and sexual ambiguity of David Bowie crossed with the eccentricity of Screamin’ Jay Hawkins, he put out two solid funk records, in which he was just warming up. It was with Dirty Mind, a ribald masterpiece that led, among other things, to Tipper Gore starting the PMRC and calling for censorship of rock lyrics, over content that still has the ability to shock: songs about masturbation, blow jobs and brother/sister incest. He continued this streak with 1981’s Controversy, replete with a title track starting with a lampoon of the Lord’s Prayer, followed by a subtle little dig at the growing segmentation of audiences “I just can't believe All the things people say, controversy... Am I black or white? Am I straight or gay? Controversy.” On these two albums, he perfected the form that he would keep with, more or less, through his entire career. Heavily resonant drums and percussion without much by the way of cymbals; Fender Telecaster rhythm guitar, an instrument rarely used outside of country music, save Bruce Springsteen, squealing analogue synthesizer and synth-bass. That “80s” production sound that for a while annoyed the shit out of everyone? That’s a Prince creation.

In 1982 he put out his most ambitious record, the double vinyl 1999. Like Stevie Wonder’s 70s period, Prince played every instrument on the album. Pushing over 70 minutes, 1999 never drags at all, combining some of the great pop singles of all time with even deeper funk, harder rock and a synth sound as overworldly as anything coming from the growing synth-pop scene across the pond in the UK. With 1999 Prince took the sonic template he’d set with his first three records and set a musical and aesthetic template that would touch artists as varied as Beck, Ween, Daft Punk and Kool Keith. Like American punk rock vocalists trying to affect a British accent, a hell of a lot of rock and R&B since Prince has had vocalists affecting a Minnesota accent, the sibiliant “ts” and “s”, the extended vowels (fast, coming out as “fa-yast”). Listen to Beck’s vocal intonations, even Michael Jackson on his post-1983 work or most recently, Drake’s half-sung choruses – this is Prince-style phrasing.

Prince was now a rock star in the height of Reagan’s America, a time of renewed conformism and neoliberalized expectations about collective political projects. The dominant themes at that time, in film and in music were taking the public’s false optimism and problematizing by showing its limits. Dated as they are, films like Footloose and Flashdance were essentially about the alienation of the body by social conservatism, the first attempt at “Making America great again”, an era captured well on the FX series The Americans. Prince took some of the great songs from his live set, notably his showstopper “Purple Rain,” and with some screenwriters, developed one of the greatest music films of all time, with that title. A sort of homage to The Harder they Come with a background more of a dysfunctional lower-middle class family and Ziggy Stardust-style dreams of escape for a character known merely as “the Kid”, Purple Rain was nearly blocked by the studios, but was released and was a huge hit. The accompanying album, a soundtrack but also a fully-realized record in its own right, was shorter than 1999, and this time more band driven and guitar heavy. It was not without subtle sonic innovations, like the eerie “When Doves Cry,” which contains no bass-instruments and uses negative space in a fashion reminiscent of the Velvet Underground.

Prince spent the rest of the 80s touring through sonic textures and making them his own, evoking the Beatles on Paisley Park with its classic singalong choruses, notably “Raspberry Beret”; adding deep funk back into the mix on Parade, the best Beck album that Beck never made. Following this was another sprawling double album’, Sign O’ the Times, in which the aforementioned political bent came to the fore once again, along with a return to a pronounced sexual ambiguity, with a number of songs sung from the point of view of a female protagonist. The references to AIDS, still spoken about in hushed tones in early 1987 accompanied angry denunciations of Reagan’s Star Wars programme and the brand-new drug, crack cocaine. Like 1999, Sign… is a long album, even longer than 1999, but it doesn’t drag and while it isn’t the most “fun’ record Prince put out, it likely stands as crowning achievement.

Prince’s followup to Sign…, The Black Album (so named as its fall 1987 release was supposed to be in a plain Black album cover/CD booklet with no credits, names or even song-listings). While there are many stories as to why it was pulled, and many more wrong-headed accounts of it as Prince’s “failed attempt to reach a black audience,” the consensus among those close to Prince is that it was recorded and written during Prince’s discovery of MDMA (Ecstasy). Prince later had a sort of “bad trip” and decided to pull the album, likely knowing it would be widely bootlegged and with the legend around it, it was “officially” released in 1994. A dark druggie/sexy record, it goes above the status of being a mere curiosity in its signification of the end of Prince’s “classic period”. The album he put out instead, LoveSexy, had some great singles, but it marked the beginning of Prince seemingly realizing he needed to grope towards a new sound. This was hinted at with his shimmering, House-influenced score for Tim Burton’s Batman reboot.

One thing that can be said about Prince in the 80s that leads us back to his song last year for Black Lives Matter. This was his sense of humility, as an artist, in particular around his main theme, that of love and sex, and the divergences and intersections between the two, the combination of intensity with matter-of-fact. As a male artist, he was certainly far from perfect, but one would be hard pressed to find celebrations of rape culture or traditional “womanizing” in his lyrics. His career of crafting mega jams about getting down while being respectful and not paternalistic and highly sexual while not being proprietary stands in stark contrast to most other performers.* Likewise, in making political statements, Prince is expository and empathic, not posing as more militant-than-thou. Nuclear war, crack, AIDS, the murder of Black youth by the pigs, these all made Prince sad.

It is sad that he died at 57, but not as sad as the world might have been had he not made it somewhat more interesting, fun, danceable and contemplative. Nothing compared 2 him.

*I owe this insight to Bryan Doherty

Jordy Cummings is a critic, labor activist and PhD candidate at York University in Toronto.