It is sad to see Brit Schulte – a founding editor – part ways with Red Wedge. If there is one constant, however, it is change. Over the past year there have been an increasing number of challenges in maintaining Red Wedge as we had been previously organized – especially as a few editors, including Brit, have been finishing up graduate degrees. More importantly, our ideas evolved in different directions. While we are sad to see Brit go, an open discussion is preferable to papering over differences. There will, we hope, be further opportunities to collaborate – and they will be more productive if we all know exactly where we stand.

Brit first raised her disagreements with the December 7th article, “An Announcement from Red Wedge” where other members of the editorial board raised the concept of a “popular avant-garde.” We feel that posting that statement has been good for Red Wedge, provoking a stream of submissions that take a deeper look at the questions of art, politics and society. That article was primarily meant to open, not close, a discussion about the direction that radical art might take. While many of our readers had their curiosity piqued by that article, others felt we buried the lead and weren’t quite sure what we were trying to accomplish. We could have been clearer.

At the same time, underneath our disagreements with Brit lay some very crucial questions worth addressing.

On the “independent art” vs. “art unfettered”

Brit writes that, rather than claiming ourselves to be in support of art’s independence (the classic line we stole, of course, from Andre Breton, Leon Trotsky and Diego Rivera), we should have argued for “art unfettered by modes of capitalist production…” While that is part and parcel of the ultimate goal (art in a fully socialist society), it is not physically possible under capitalism itself. In fact it is outright impossible. Materially, one is either sufficiently wealthy to produce art (which means you are living off capital accumulation), or you live off wages, grants, the sale of artwork or books or record and ticket sales, etc. There is no escaping the constraint of capitalism. Moreover, ideologically the influence of capitalism impacts even the most class-conscious workers, let alone artists. There is no escape from the influence of capitalism either.

If one were to quit civilization and head into the woods, creating art without electricity or running water, one might be able to create “art unfettered by capitalist modes of production, criticism, etc.” Capitalism, like it or not (and we don’t like it), has full-spectrum hegemony over our political, economic and cultural lives.

This does not mean that all is lost. While we can’t step outside of capitalism we can create art that positions itself against this capitalist hegemony. There is room in contradiction – and capitalism constantly reproduces contradictions. The most interesting art does not deny these contradictions but exploits them. This is not simply a matter of taste or preference – it is recognizing a dynamic of artistic production within capitalism. It is this reality that has preoccupied the virtual entirety of Marxist and left-wing cultural criticism (from Walter Benjamin to Judith Butler). They did not pretend such things could be wished away. Neither can we.

On “revolutionary projects” vs. “revolutionary socialist projects”

We (the Red Wedge editors) are socialists because we believe that the socialist – in particular the Marxist – tradition offers the best way forward for art and workers and oppressed people generally. We are anything but doctrinaire in our Marxism. We see no value in calcified theory or merely repeating what has come before. The classical Marxist framework is supple, dynamic and learns from its mistakes. This was why we opened up a “special discussion” about the direction of Red Wedge in December. We are open to learning from and publishing from other left traditions (as we have been since the beginning) – posting material on art and culture from allies with anarchist, left social-democratic, queer and other frameworks. We have much in common. But, if we are Marxists, we can’t pretend that we believe all these traditions have the same strengths and weaknesses. Such a posture, not merely using the word “socialist,” muddies the water.

On the avant-garde and elitism

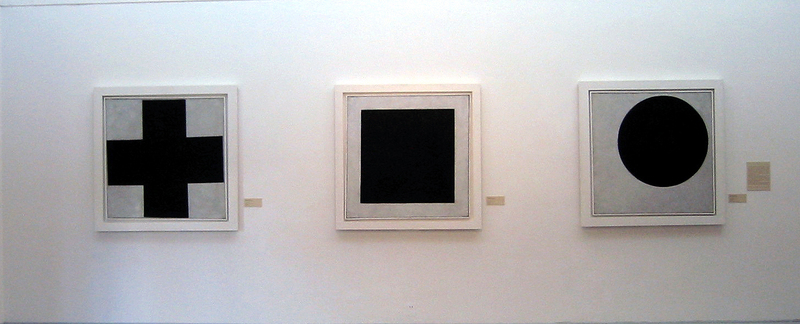

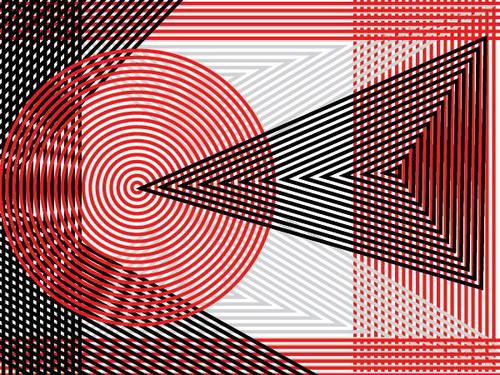

Yes, there is an exclusivity to the term “avant-garde,” but it is not, as Brit argues, inherently elitist. The avant-garde is not an invention of artists and academics. It is an organic product of capitalist culture: borne of uneven and combined cultural development. The avant-garde, in terms of cultural production, remembers the past and anticipates the future. It is our responsibility to shape it and reorient it toward popular and radical concerns. The avant-gardes of the 19th and 20th century repeatedly focused on popular concerns (and radical politics), as Brit’s own writing has shown. This connection has been broken by the trajectory of capitalism, the collapse of “really existing socialism” (such as it was), the neoliberal turn, and its postmodern and poststructuralist philosophies. This connection can be re-stitched and remade. It is one of the many reasons we are exploring the idea of a popular avant-garde: to demystify what it means to make such art.

More troubling is Brit’s insinuation that this is not possible – that the avant-garde is beyond the reach of “ordinary people” and contemporary culture workers. We do not believe that Brit actually believes this but her words say otherwise. We feel this proves the need for us to reclaim a popular avant-garde – not as a genre or kind of art, but as an outlook that engages with art outside the mainstream (the hegemonic mainstream) and within it (with the working-class majority). “Nothing should be off limits,” Brit writes. We agree. We try to make that clear in the material we publish and post.

On insufficient ways to describe oppression

Should we have used the words “systemic, institutionalized racism and environmental racism” rather than what we wrote? Perhaps, but the entire paragraph in question reads as such:

The hope of the Arab Spring has been subsumed by the barbaric farce of “ISIS vs. the West.” The far right is on the ascendancy in many countries across the globe. And despite some real and important victories, BLM is facing off against the state itself, against “special bodies” of armed men and women who are as central to U.S. capital as Wall Street itself. This is not to mention the ongoing refugee, climate, and other crises.

There is always potentially a better way to put things. And it bears mentioning that since the publication of this statement, there have been strikes in Tunisia and Egypt, protests in Saudi Arabia, large demonstrations in Syria celebrating the fifth anniversary of the uprising. Hope may go into hiding, but it never really dies. At the same time climate change and war roil on – and the revolutionary left (Marxists included) remains too small to impact these historical processes. Regardless, it is difficult to say, in the context of the above paragraph, we are “dismissive” of any of these struggles. Moreover, again, the work we have published proves that we are not.

On bridging the activist and the theoretical

Brit writes:

What is the "wall" between activist and intellectual? Is it grad school applications, the lack of tenure-track positions, or the absence of opportunities for academics to participate in social movements? Believe it or not, workers think and thinkers work. Where are the workers that DON'T read in the Brechtian sense? Who are the synthetic or inorganic intellectuals against which Gramsci might rail?

Here Brit engages with something that we didn’t write rather than what we did. All of these things throw up a wall between activists and intellectuals – and more. That is the reality of capitalism and particularly neoliberal capitalism. These things are related to the attacks on public education and the arts, and reshaping each to the needs of capital – subjects that Red Wedge, and Brit herself, have written on many times. But this is not the point we were making.

We were referring to the problem of consciousness. Most workers do not read “in the Brechtian sense.” A majority of workers are not Gramsci’s “organic intellectuals” (we aren’t quite sure what Brit means by “synthetic intellectuals”). What Brecht and Gramsci argued was not that workers don’t think or read, but that most workers don’t yet read or intellectualize in a fully class-conscious manner – in ways that reimagine the world and rewrite future history. If the majority were Brecht’s “workers who read” or Gramsci’s “organic intellectuals” we would be on the precipice of revolution. We aren’t.

The question is: how we help create more workers who read, more organic intellectuals – and what is the role of artists in this creation? We believe, more than most, that “workers think and thinkers work,” which is why we are dedicated to breaking down the barriers between “head” and “hand.” In the very same paragraph that Brit criticizes we argue “There can be no room among cultural Marxists for snobbery (against workers or, conversely, ‘difficult ideas.’)”

On space for artistic initiatives

We are somewhat nonplussed by Brit’s argument that we can make working-class narratives central by “funding them.” Where is this money coming from? From Red Wedge? Red Wedge can barely keep our website up and materials printed. All of our current and former editors know this – including Brit. We could take the few thousand dollars that our editors, writers and supports have donated to Red Wedge and funnel all of that into others’ projects. That would be worthwhile, but it would be a fundamentally different endeavor than what Red Wedge set out to do. And it would not be, in the long term, sustainable.

We’ve desperately wanted to do more – put on concerts, panels, art openings and films. But we are constrained by the fact that we are all workers and students. Where would resources come from? Our donors have been generous. We owe them everything. But times are tough. Most can only afford to give a little – if anything. (Don’t forget – donate to Red Wedge!) We wish there was a short-cut. But the radical cultural renaissance that we and Brit want is still struggling to be born.

We will never underestimate the ability of workers to engage in criticism and artistic production. A degree does not a critic make. Engagement with the world does, and a growing number of poor, working and oppressed people know this. This has been borne out by the poets, writers and artists whose work we have published – women, people of color, queer folk, working people and every permutation of all of these – and will continue to publish. It has also been borne out by our editors’ involvement in attempting to launch projects like the November Network of Anti-Capitalist Artists. Other similar endeavors are likely on the horizon.

Which begs the question: When Brit says “You get in touch with folx already doing this work, you band together, and build community,” what does she think Red Wedge has been doing? Why does she think that we will now be doing less of it? If our engagement thus far has been lacking, then we can only say that we hope we can find opportunities to redouble these efforts in the future.

We wish Brit well. We have no doubt that we will have opportunities to work with her in the future on other projects. If we have not convinced her or those who might agree with her, then perhaps the time has come to, as the saying goes, “show not tell.” As Brit ends her letter:

So here’s to making music, and writing criticism, to highlighting visual studies, and aesthetics, and to exploring performance and absolutely rekindling the revolutionary imagination.

We could not agree more.

"Feuilleton" is the Red Wedge editors' blog focused on announcements, events and relevant debate.