This essay is an expanded version of a presentation given at last fall’s Historical Materialism conference held at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. It was part of a broader panel presented by Red Wedge launching our new pamphlet “Notes For a 21st Century Popular Avant-Garde.” The pamphlet is available for purchase at wedgeshop, and to all those who join the Red Wedge Patron program.

* * *

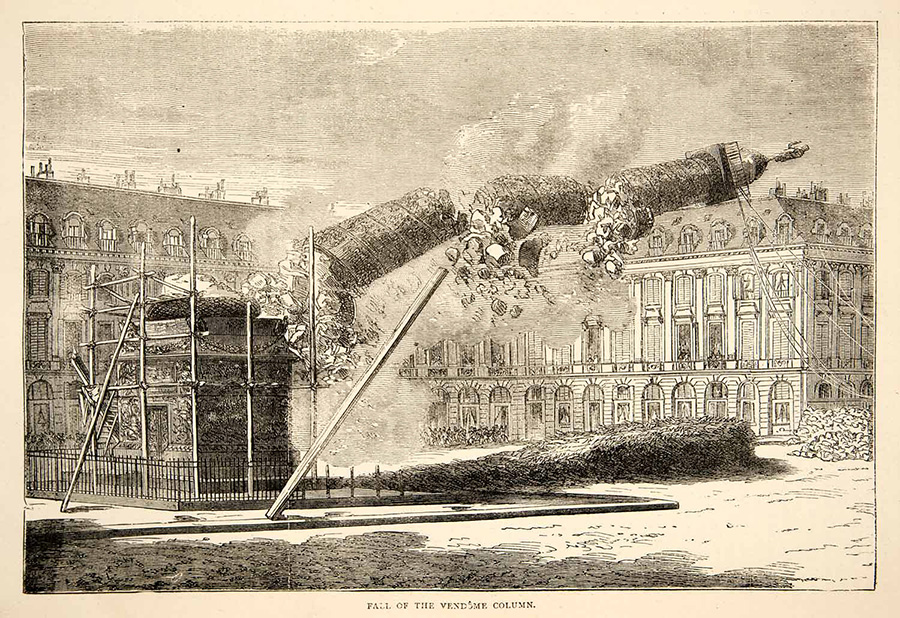

In 1871, Parisian workers famously brought down the Vendome Column in the city’s first arondissement. It was an iconic event – in more way than one – for the Paris Commune. The Column, erected sixty years previously in commemoration of Napoleon’s victory at the Battle of Austerlitz, was torn down at the initial suggestion of the legendary artist Gustave Courbet. Courbet called the Column “a monument devoid of all artistic value, tending to perpetuate by its expression the ideas of war and conquest of the past imperial dynasty, which are reproved by a republican nation's sentiment.”

Courbet was a leading member of the Commune’s Artists Federation, which brought together not just painters but lithographers, ornamentalists, and a great many artisans and workers who before had their craft demeaned as “beneath art.” The Artists Federation’s purview, in its short time, was to not just promote revolutionary art, not just to open it up to the masses, but in so doing question the aesthetics of everything, the arrangement of daily life, inviting ordinary Parisians to literally make it anew.

The obliteration of the Vendome Column wasn’t just a negation, but an assertion of an alternative. In place of the old exploitative order, with its staid approach to the arts as works of “genius,” the Commune was to present the arts as radically participatory, and beauty as something that is both enjoyed and created by working people.

Today there is no shortage of monuments being torn down. An estimated 300-plus statues of Lenin were felled across Ukraine during Euromaidan in late 2013 and early 2014. Across Iraq, Syria, and parts of the Maghreb, ancient works of art are demolished by Daesh. Historic architecture and statues that date back thousands of years have been turned to rubble. In Libya, they burned musical instruments and executed musicians on camera.

These are not extremist fringe actions. They emerge from a specific moment and are shaped by a broader cultural logic. The new president of the United States is a man who, in his real estate developer years, willfully destroyed historic American architecture to build hotels and casinos. When Detroit fell into bankruptcy four years ago, its creditors demanded that the Detroit Institute of Arts contribute $500 million to the recovery through massive sales of its collection (which was only avoided when the DIA went on a massive fundraising drive). For the past several years, pundits have speculated whether the debt-ridden nation of Greece might be forced to sell the Acropolis. (In an odd confluence, an apocryphal story has Donald Trump suggesting that he build a hotel next to the Parthenon as a solution to Greece’s debt crisis. True or not, it is telling.)

The destruction of these monuments is indeed a negation of a sort, a muddled rejection of past orders, no matter how valid these orders might have been, but into the remaining void they inject only a deeper nihilism. The barbarity of the current order is laid bare, but is fundamentally unchanged. History and culture are erased so that their trajectory toward a cancelled future remain unaltered.

In the midst of all this, is it even worth talking about art? Or has “no poetry after Auschwitz” – the vulgarized version of Theodor Adorno’s old adage – merely adapted itself to “no music after Daesh”?

We should ask this question with the proper anthropological context. Art, for most of human history, was not a discrete category of existence. Itwas integral to not just understanding what was in front of human beings but ordering it next to our sense of what could and should be. As Maynard Solomon tells us:

Art simultaneously reflects and transcends; says “Yes” and cries “No”; is created by history and creates history; points toward the future by reference to the past and by liberation of the latent tendencies of the present.

This description captures a capability possessed by painting, literature, music and other art-forms that is completely unique to them. They defy the rules of time and place. Not literally of course, but in a metaphorical way that is more vivid than any other medium of existence. All are able to take the senses and consciousness of whomever is reading, viewing or listening and transport them to another time and place. A song can make time slow down or speed up in the perception of a listener. It can provoke a sensation of time in the observer that is counter-linear, that is not just one thing after another. Well-composed literature can do the same thing. An engaging story, poem, painting or sculpture puts you in a place other than where you physically are.

The actual stars and wheat fields that comprise the subjects of Van Gogh’s paintings do not literally swirl and undulate out of their physical location. That is not what makes the paintings matter. They do not describe what already is, but nor do they make fiction out of thin air. They acknowledge that, in the right moment, we already experience stars at night and wheat blowing in the wind as iridescent swirls and endless water-like waves on land. The subjects are still, but we “see” them move. The real expands beyond the confines of reality. That this intellectual, emotional and social interaction plays a central role in human existence speaks to our own capability to conceive of the world as more than just what we see in front of us.

A popular avant-garde, first and foremost, regards this as its starting point for understanding human creativity. It is both a critical framework for approaching art and an artistic praxis that deliberately foregrounds’ the human capacity to collectively remake and repurpose.

Torn halves

Both “popular culture” and “avant-garde art” are, depending on who you are talking to, worthy of derision. To many people, the very term “avant-garde” seems mystified, elitist, inaccessible or even prohibitive to ordinary people. And to be sure, there is a strong vein in experimental art, music, literature, film – some might say dominant currently – that is overly formalistic, obsessed with experiment for the sake of experiment, possessing little concern for whether masses of people are able to engage with what the artist is saying.

On the other hand, the term “popular culture,” for many, smacks of art made solely for the sake of profit: shallow, derivative, devoid of substance and playing to the lowest common denominator. To critics of the popular – whether they consider themselves adherents of the “underground,” the “experimental,” the “avant-garde” or just the “un-popular” – this is a lesser form of art or not art at all.

Each of these have manifested counterparts in how the contemporary Left regards art. Some radicals are wholly dismissive of mass culture, seeing it as bought-off pabulum. In turn, they fetishize the underground or the “craftivist,” their suspicion automatically kicking in as soon as “too large” an audience is reached.

Others strike a posture of cultural populism, searching for hidden radical kernels in blockbuster movies and hit singles (even finding ones that simply aren’t there). They have little consideration for how the aesthetics of these works can easily metabolize and redirect progressive narratives into ideologically safe cul de sacs.

Both accomplish a reflexive elitism, ultimately undercutting the idea that working people can ever reinvent themselves. Both end up focusing on content – including the wholesale invention of meanings that aren’t there – at the expense of formal analysis. Both underestimate or ignore entirely the temporal and spatial possibilities of art and their interactions with an autonomous, democratic imagination.

The point here is not to say that these lines of thought are entirely wrong – or at least, we aren’t saying that there is something fundamentally wrong with the impulse behind them – but rather that each of them is missing the other side. They are, again borrowing from Adorno, “torn halves of an integral freedom, to which however they do not add up.”

The popular avant-garde asks where the locus might be in re-joining these two halves. What is the role of socialists if not to make radical ideas – fringe ideas even – popular? To push those ideas into the mainstream without allowing their radicalism to be compromised? And what is that radical idea? It is the idea that working people themselves – those who comprise the vast majority of the populace – can control the production and reproduction of daily life.

Despite the current friction between the two terms, there is in fact an organic and historic connection in what they represent. The first use of the term “avant-garde” in relation to the creative arts did not come from a critic but from a utopian socialist named Olinde Rodrigues in the 1820’s. In his essay “L'artiste, le savant et l'industriel.” Rodrigues demanded “artists serve as [the people’s] avant-garde.”

It is worth taking Rodrigues’ comments with a few grains of salt, as we should all the utopian socialists. But there is an interpretive kernel worth grasping here. Rodrigues’ words reflect something about the role of art in joining ordinary people with an alternative future. And in a world where work and narratives have been fragmented, segmented and divided, not only their charm but their meaning stripped of them, the imagination of a future is more important, not less. And if a key dividing line of artistic and cultural production can be bridged, then a key part of the revolutionary imagination might be salvaged.

Definitions and insurrections

First, we should establish a working definition for “popular culture.” Stuart Hall defined popular culture neither as a pure expression of working class life totally autonomous from the dominant classes, nor as purely a means of domination. Rather, in Gramscian fashion, it is a site of struggle for hegemony, and the varied meanings within it can be defined and redefined depending on the balance of class forces and the resources available to the competing classes. Sites of struggle are sites of both conformity and rebellion, achieving an equilibrium that is often uneasy.

Locating and defining the “avant-garde,” therefore, requires not looking outside popular culture’s parameters and dynamics, but within them and the tensions they create. Even the modernist avant-garde of the twentieth century, which seemed to (and in many cases did) shun so much of popular culture were, in their reaction against it, also shaped by it. Artists, composers and writers of the period often deliberately reappropriated techniques and images from within popular cultural expressions even as they irreverently inverted them for critique.

In The Necessity of Art Ernst Fischer tells us about the relationship between content and form in artistic production: dramatic changes in the composition and experience of class society grant artists new content to work with, which in turn pushes the form of the artwork and forges a dialectical bond between the two. Peasant ballads flood into the city as the commons are enclosed; they collide with the observations and disillusionment of artistocratic poets, impacting the formation of romanticism.

Though the rebellion of romanticism came well before anything such as the avant-garde was materially possible, we do start to see something of the ebb and flow between what is at the center of aesthetic convention versus what is outside of it one day to the next.

This results in a fascinating paradox: so much of what is deemed “new” in the avant-garde is in fact merely shedding light on what has long existed but been deliberately ignored by narratives of “progress.” What’s more (dovetailing with Maynard Solomon), it gives the latent, the ignored and left-behind a life of its own, an autonomy that is ill at ease with the condescension of mainstream “underdog” stories.

Narratives, gestures and figures that otherwise can be easily recuperated into stories about perseverance and pulling yourself up by the bootstraps are retooled and re-arranged. They are reinterpreted and physically placed in opposition to the logics of capital that put them in the back of the bus in the first place. The wretched arise, the “left behind” become the vanguard.

The approach illustrated above – which finds its explosiveness not outside the popular but within its contradictions – can be equally applied to how radicals view the means of producing culture. Even as the industrial process has, in the view of those such as Adorno and Clement Greenberg, rather cheapened the arts, it also rather ironically created possibilities for cultural production to rebel against this same process. And, crucially, for that rebellion to reach wider swathes of people.

This is precisely what motivated Walter Benjamin to write his landmark “The Work of Art In the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” The essay illustrated how it is that mass industrialization has deprived original art of its “aura,” but it also posited what might replace that aura. If the mass reproductive technology made it possible to bring the images of a painting out of the private gallery, the notes of a composition out of the concert hall, then Benjamin wished for us to envision what it might be like for these productive forces to be under mass democratic control. Even if his primary illustrative example was a negative one – how the machinations of fascism used the reproduction of art to bolster and supplement vicious hierarchies – he leaves us wondering what might be possible if mass democratic participation in the cultural and aesthetic process were a reality.

Capitalism had made it possible to feed and clothe everyone on the planet, but does not do so because its resources are allocated in such a way as to meet the needs of profit, leaving millions hungry, homeless and destitute. In a similar fashion, the culture industry’s vast resources should in theory allow every human to take part in the creation and recreation of culture, art and aesthetics. This same industry’s structure prevents such participation, however. Only a select few are granted the virtually unlimited resources needed for true creative freedom, and even then they are subject to the glass ceilings of profit and market considerations.

Changing this, not just shattering the ceiling but reorganizing the structure and reallocating the resources, wouldn’t just allow for new or long-ignored stories to be told, but for new methods with which to tell them. Not just new content, but new forms.

The historical association between large sectors of the avant-garde and radical emancipatory projects isn’t merely happenstance. It isn’t simply that modernism rose hand-in-hand with a working class radicalized by an anti-capitalist alternative. The affinity is itself a reflection of the need to turn capital’s cultural logic upside down and inside out, allowing its assets to fall into the hands of ordinary people who, in their insurrection, become artists of everyday life.

We should, with this as a starting point, interrogate how it is that a work of art, literature, music or film might use recognizable signifiers and gestures – ultimately emerging from somewhere in the past – and direct them toward the future. The reproductive process can allow past cultures, movements and building blocks to be redeployed – however they’ve been bestowed in the past – to redefine the narratives around each one, taking the meanings of the past and redirecting them into a meaning that is each but none. Culture and history as process, the entry of ordinary people into that process, yielding to an alternate future.

(Re)claiming the popular avant-garde

This is a pattern that runs throughout the history of the avant-garde, and it is why the concept of “the popular avant-garde” is not a new one. As Renee M. Silverman explains in the introduction to the book of the same name:

The artistic experimentalism and anti-bourgeois attitude of the vanguard successfully turns the raw directness of popular genres into searing political irony and satire, but only because the popular in these cases acquires a political function with respect to the avant-garde, forcing it to maintain a self-conscious honesty about mass destruction and oppression. The popular here is essential to preventing the avant-garde from folding in on itself and hiding its face from those who most need to receive its message. The “popular avant-garde” avoids the divorce of art and praxis, or everyday practice, of which the avant-garde has been accused.

Bertolt Brecht’s epic theatre, Frida Kahlo’s surrealism (which managed to seamlessly exhibit a vivid Marxism, feminism, and indigeneity all at once), the mobilization of punk, reggae, ska and youth culture that was Rock Against Racism. All of these could be considered avant-garde for their time and place, or at least outside of predominant aesthetic convention. All utilized temporally dislocated aesthetics, what had existed previously or existed currently as cultural detritus. All engaged or attempted to engage, with varying levels of success, the poor, the disenfranchised, the oppressed. At their best, they demanded that people engage with them to transform the art’s past meanings in relation to the present, and in so doing conceive of an alternative future.

How then, with these traditions at our backs, have we arrived here? Capitalism has always relied on a division and distribution of labor that parcels every task out to its most meaningless fraction. But neoliberalism’s iteration of this has proven – particularly since its recovery from the 2008 crisis – to be uniquely insidious. The line between our personal lives and work is blurred. Most labor takes on an emotional component of one kind or another.

We are told that we are all entrepreneurs and artists, that we must “do what we love.” Meanwhile, virtually every aspect of our lives has been not just monetized but is sold back to us as a means of survival. “Sharing economy” is a wonderful term, but it covers for the fact that AirBnB, Uber and all the rest enable for an almost unprecedented transfer of wealth upward.

Likewise, we are told that the internet has democratized art and culture, when in fact it has enabled the culture industry to become more consolidated and far-reaching than ever, making it easier than ever to seek out and mold new talent into something that can be metabolized into the aesthetic logic of the commodity.

The so-called avant-garde, on the other hand, has adopted a mirror image of this position, attempting to escape the commodity by making works that are self-contained, impervious to interpretation, cynical in their relationship to the audience.

Both exhibit a logic that anything can be art. This isn’t in and of itself untrue, but both also rely on a qualifier. Anything can be art so long as the right people deem it so, reinforcing the separation of producer and passive consumer, as well as top-down ideas of “genius,” and selective entitlement to the creative process.

Both rely on the cult of celebrity, of envy. This is an emotion of, as John Berger writes, “[t]he industrial society which has moved towards democracy and then stopped half way.”

Both, no matter how they conceive of themselves in relation to the commodity, adopt the pretense of the commodity as eternal, as something outside of time and created apart from history.

Is it any wonder, when this mode of imagination prevails, that empires can produce an army literally bent on destroying history, destroying cultural legacies rather than reshaping them?

Against this, revolutionary Marxists are in more need of an aesthetic lens like the popular avant-garde. Not less. A viewpoint that avoids the twin traps of cultural populism and underground obscurantism, and puts mass, radical, democratic reinvention at its center.

If we know where to look – or, more specifically, how to look – we can critically identify where this tradition already exists, where it can be cohered. The jazz-rap engagement with the pain of Black lives in Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly, the absurd, vulgar lampooning of late night talk shows on “The Eric Andre Show,” the poetry of Warsan Shire.

As for examples more organically connected with critical socialist and radical traditions, they can be seen in the tragic hauntings of playwright Caryl Churchill, the inversions of digital globalization produced by M.I.A., and the “dystopian soul” of the band Algiers.

What is it that sets these apart from other forms of popular or avant-garde art? What is it that places them – consciously or unconsciously – alongside Brecht, Kahlo and Rock Against Racism? Benjamin in “The Work of Art” spoke of the “aestheticization of politics,” the use of art’s auratic defiance of time and place to further ingratiate people to an exploitative system. Against this he contrasted “the politicization of art,” not the reduction of art to rote slogans or didactic rants, but consciously placing it within the historical process, and therefore strengthening the participatory engagement of artist, viewer, poet, reader, musician, listener.

These are works of art that, in their conscious aesthetic intervention into history, make art itself move. Each of them, in their own way, hint at what it might mean for the vast resources of the culture industry to be in the hands of working and oppressed people, democratically reshaped to their imaginative needs.

It is an aesthetic approach that shares the fundamentals with the tearing down of the Vendome Column and the Artists Federation. There are indeed countless monuments today that deserve to be torn down. What takes their place is of course an open question, but it need not be completely unanswerable.

Red Wedge relies on your support. Our project is both urgent and urgently needed for cultivating a left-wing cultural resistance. If you like what you read above, consider becoming a patron of Red Wedge.

Alexander Billet is a writer, poet, and cultural critic. He has written for Jacobin and In These Times, and is chief editor at Red Wedge. He blogs at Dys/Utopian, and further pollutes the cesspool of Twitter through his account: @UbuPamplemousse